The Revolution Will Be Mainstreamed. On Pop Culture Absorbing Black Music

A note from the staff: as Cactus, our main goal is to focus on Arts, and in this specific case we will analyze the role of music in the new civil-rights movements evolving in the last few weeks. While doing this, we won’t get deep into the political commentary, but this doesn’t imply we aren’t taking a clear stand against any form of discrimination and oppression. We, the whole Cactus team, strongly believe Black Lives Matter.

A note from the staff: as Cactus, our main goal is to focus on Arts, and in this specific case we will analyze the role of music in the new civil-rights movements evolving in the last few weeks. While doing this, we won’t get deep into the political commentary, but this doesn’t imply we aren’t taking a clear stand against any form of discrimination and oppression. We, the whole Cactus team, strongly believe Black Lives Matter.

The world outside is constantly changing day-by-day and – even if 2020 got us used to it – it’s almost hard to keep up. As we write this, we are witnessing history being made. The death of George Floyd has been followed by protests all across the U.S. and the rest of the world. What started the riots after the umpteenth African-American killed by the police led to the largest global demonstration against police brutality in recent years, which then turned into an even broader event against systematic racism in modern society.

Besides the political and social aspects of the circumstance, there is an interesting take about the role of music in this “American Spring”.

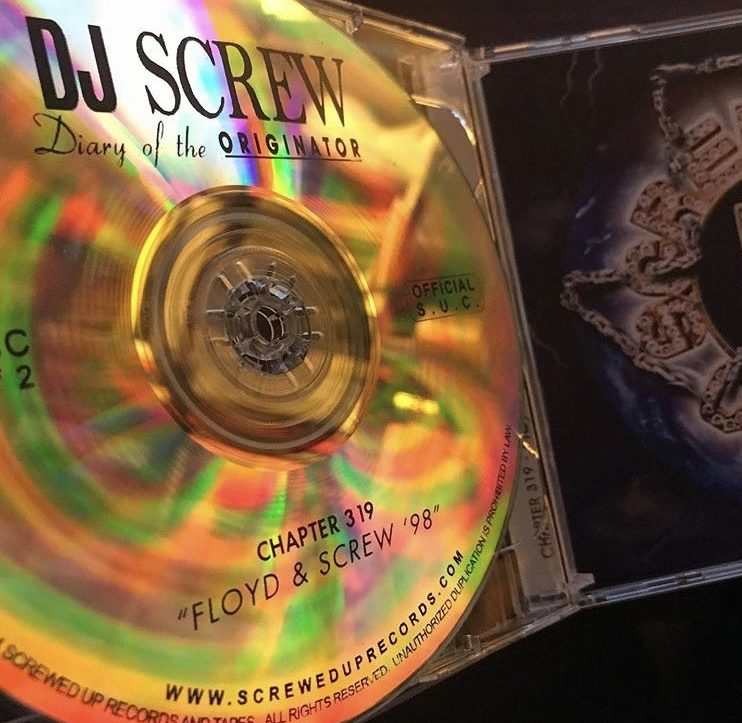

The first way music immediately gets a role in the story comes by a less-known side of George Floyd: in the ’90s he was a rapper who went by the name of “Big Floyd”. During his years in Houston Floyd was a member of the most revered and influential crew of the city: ‘The Screwed Up Click’. The founder, DJ Screw, is a pivotal figure in Houston whose slowed-down style influenced countless artists of different genres through the following decades. Just typing on YouTube “Big Floyd Dj Screw” you can find his verses in the trademark “Screwed and Chopped” style. But there is even more. Floyd, even decades after he left Houston, kept a connection with the local music scene. The proof is a cameo he did – wearing a red “Screwed Up Click” sweatshirt – on the F*ck You Too music video, performed by the Hip Hop legends Scarface and Z-Ro, in 2016.

Anyway, don’t expect to hear Big Floyd’s music blasted through the speakers during the marches – his rap career it’s still a little known hidden gem. As a matter of fact, it is even hard to predict what to expect to hear during these early stages of this this rising revolution.

Anyway, don’t expect to hear Big Floyd’s music blasted through the speakers during the marches – his rap career it’s still a little known hidden gem. As a matter of fact, it is even hard to predict what to expect to hear during these early stages of this this rising revolution.

Kendrick Lamar’s Alright was the global anthem for the 2015 Black Lives Matter protests. It came out in 2015 as the fourth single of his afrocentric-themed album ‘To Pimp A Butterfly,’ and it simply was the right song at the right time. In 2020 the situation is different. Of course we have seen a lot of “slacktivism,” with some artists just posting something on social media, but we’ have also seen different forms of participation from musicians, which widely ranged from making huge donations, to joining the protests, to moving behind the scenes in support of the families of the victims.

Basically, today’s music scene is having a role through every aspect, except producing new “conscious” anthems. This is an unprecedented situation.

In the absence of this year’s Alright, however, people still needs the power of music to create a point of connection between them, and the outcome is that the soundtrack of the 2020 rallies is, to say the least, diversified: you find people marching singing James Brown’s Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud, or hearing Techno music (in Detroit, of course), or countless Rap songs like 2Pac’s Changes, YG and Nipsey Hussle’s FDT (the acronym of “F*ck Donald Trump,” no explanation needed), Childish Gambino’s This Is America (the Caucasians’ favorite), Future’s March Madness (maybe because of the line “all the cops shooting n*ggas: tragic,” or maybe because it is the greatest rap song of its generation), the recently passed Pop Smoke’s Dior, or Chief Keef’s Faneto (when I saw it, I knew that rioting and looting were about to happen).

Looking at it, it is like black musicians are reluctant about the idea of guiding the revolution with their records.

Looking at it, it is like black musicians are reluctant about the idea of guiding the revolution with their records.

Black Music has a well-established tradition of social commentary. Songs like Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit, or Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come have lyrics that are still relevant today despite being released in 1939 and 1964.

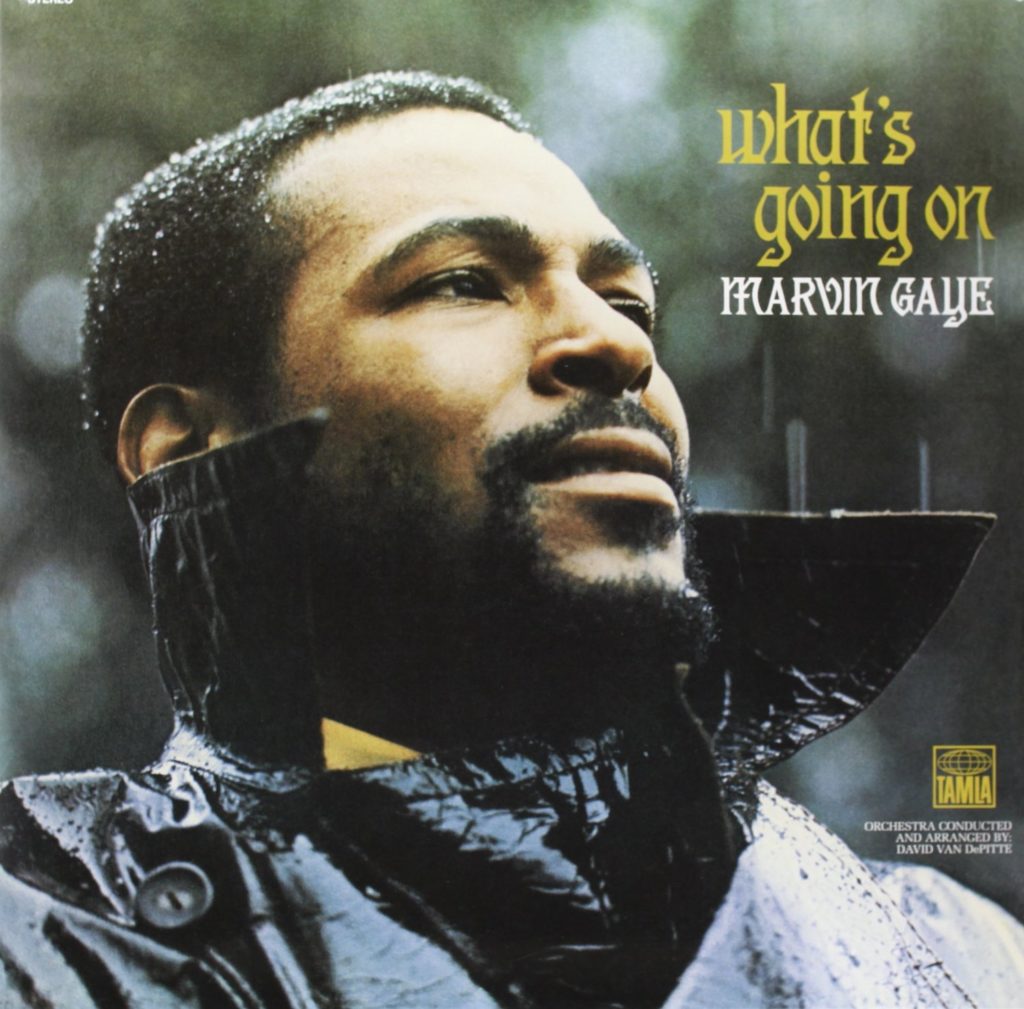

In 1970 Marvin Gaye went against his label owner, Motown Record’s boss – Barry Gordy – who didn’t want to publish his new album ‘What’s Going On,’ saying it was too political and commercially unappealing. Gaye went on a strike, refusing to record any new song until he had Gordy’s approval for the album. ‘What’s Going On’ finally came out in 1971, becoming one of the soundtracks of the 70s social and political tumult, and inspiring other so far less socially committed artists – like Stevie Wonder – to give their music a higher purpose.

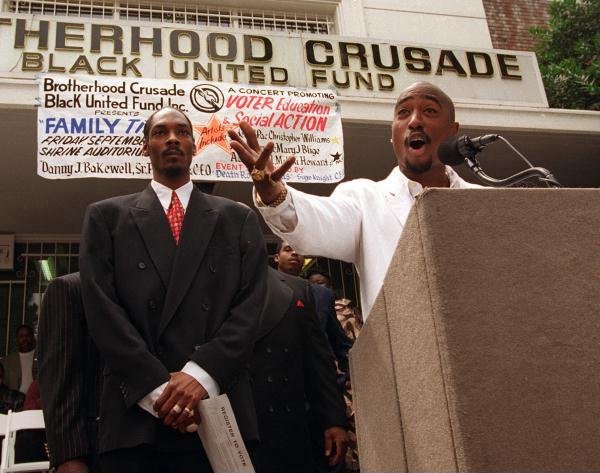

Other examples of leadership through music can be found in other troubled times: such as the first half of the 90s. In this era, Rap took the place of Soul in the 70s, and an extensive number of rappers presented themselves as revolutionaries, trying to connect with the community and inspire people. In 1995, black men from all across the country united for the “Million Man March” in Washington D.C., and Hip Hop artists playing a major role in appealing to young black men. It was clear that they weren’t simply rappers, they were leaders. The examples were many: Ice Cube, Geto Boys, Chuck D, KRS-One, Mos Def, but most af all: Tupac Shakur.

I guess ’cause I’m black born

I’m supposed to say peace, sing songs, and get capped on

But it’s time for a new plan – bam!

I’ll be swingin’ like a one man clan

[2Pac – Holler If Ya’ Hear Me]

It is clear that the Black Music scene today lacks a modern 2Pac. It lacks a musician with the role of a civil rights leader. But does today’s Black Music actually needs it? Are we supposed to look at the 2020s through the same lens of the 70s, the 90s, even the 10s?

It is clear that the Black Music scene today lacks a modern 2Pac. It lacks a musician with the role of a civil rights leader. But does today’s Black Music actually needs it? Are we supposed to look at the 2020s through the same lens of the 70s, the 90s, even the 10s?

If until a few years ago it was difficult to think of outlining a music horizon without a firm leadership that addressed and guarded ideologies, today the panorama is so complex and broad-spectrum that the need to class it up using anachronistic mapping models seems to be no longer necessary.

Black Music can still be the voice of the oppressed, the voice of the pain and struggle, its eyes are still watching the streets, its protests, its claims, but Black Music today it is the new Pop – who has totally absorbed Hip Hop and R&B. What used to be against the mainstream, now has completed his transition into it.

Once realized and embraced this transition, it’s maybe time to stop waiting for the new Strange Fruit, while being ready to embrace the next They Don’t Care About Us.