Design Narratives. On Sonic Arts and the Creations of Worlds

One of the core elements in contemporary visual and audio culture is, without a doubt, the creation of narratives: everything needs to merge together in different shapes to give life to a sequence of events, materials, designs, memories, and objects. The creation of an art product requires the creation of a narration, that it has been affected and shaped by other narrations − and that could affect in turn.

One of the core elements in contemporary visual and audio culture is, without a doubt, the creation of narratives: everything needs to merge together in different shapes to give life to a sequence of events, materials, designs, memories, and objects. The creation of an art product requires the creation of a narration, that it has been affected and shaped by other narrations − and that could affect in turn.

In recent years, technology helped to land into an unknown territory of representation and interactivity, in part due to the sky-rocketed evolution of game design as an affective tool, capable of modelling new scenarios in contemporary practices. Therefore, game design is a combination of different elements able to spread into every mode of expression, such as visual contents, sonic objects, screenplays, coding, interactive components and so on.

Nevertheless, what I really would like to highlight in relation to this particular context is the combination of sound and game design as innovative tools to establish new systems made of environments and worlds.

The role of sound in games has been always identified as something more related to a decorative purpose rather than a central one. Instead, my research is focused on its own deconstruction, departing from the standard use of the soundtrack and audio effects and in favour of a more affective and conceptual approach.

As I explained, narratives had their basis in the conjunction of affected objects from different territories, making game design as a privileged field in the creation of worlds. Sound design, on the other hand, develops itself on a temporal progression − a succession of events and elements − and this feature brings this analysis on the next level: narratives are a succession of objects, distributed on a sequence of events not necessary linear.

The creation of a narrative environment through sound design also aims to establish a defined aesthetic in some product. On a basic level, we could look for example at the renowned mixture of industrial noise, minimal electronic music and a certain kind of J-Rock in the Silent Hill series’ early releases, that helped to shape a peculiar and landmarked aesthetic based on the distinctive anxious affect of the survival horror genre.

The creation of a narrative environment through sound design also aims to establish a defined aesthetic in some product. On a basic level, we could look for example at the renowned mixture of industrial noise, minimal electronic music and a certain kind of J-Rock in the Silent Hill series’ early releases, that helped to shape a peculiar and landmarked aesthetic based on the distinctive anxious affect of the survival horror genre.

But it is in the second chapter of the franchise, Silent Hill 2 (2001), that the audio section of the product works on a deeper role. The plot of the game revolves around James Sunderland and his blurred memory about the death of his wife Mary; proceeding with the story, the audience will discover that James subconsciously creates an alternative version of his past to cover and bury the truth about the fact that he is the true murderer of his wife.

The sonic melange made of oppressive field recordings, lullabies and melancholic guitar riffs becomes a hauntological narrative element in the soundtrack composed by Akira Yamaoka. The audio section of the game is pervaded by a twisted veil of tape-loop effect and a general gloomy ambience, that runs in parallel with the whole scenario to create a distorted present dimension made by a never happened past. The ghost of a gnarled event that haunts the reality of the entire experience. It is easy to trace a parallel between the soundtrack of Silent Hill 2 and The Disintegration Loops project (2002-2003) by William Basinski, one of the most representative examples of hauntological music of the last twenty years.

However, the ambience created is particularly remarkable not only due to the eerie result in-game but also as a reflection of some tendencies in the pop-cultural field on a broader acception, as the spreading of post-metal tunes and the new goth and rave aesthetics in cinema and fashion in the late ‘90s/early ‘00s.

Composer and researcher Emile Frankel discuss the role of sound design as a creator of dreadful and non-anthropocentric environments in his text Hearing the Cloud (2019). He focuses on the sound design of the Dark Souls series (2011-2016) and its uncommon and disturbing method of using sound as an affective tool after stepping into some Youtube playlists dedicated to the ambient sounds of such game.

Composer and researcher Emile Frankel discuss the role of sound design as a creator of dreadful and non-anthropocentric environments in his text Hearing the Cloud (2019). He focuses on the sound design of the Dark Souls series (2011-2016) and its uncommon and disturbing method of using sound as an affective tool after stepping into some Youtube playlists dedicated to the ambient sounds of such game.

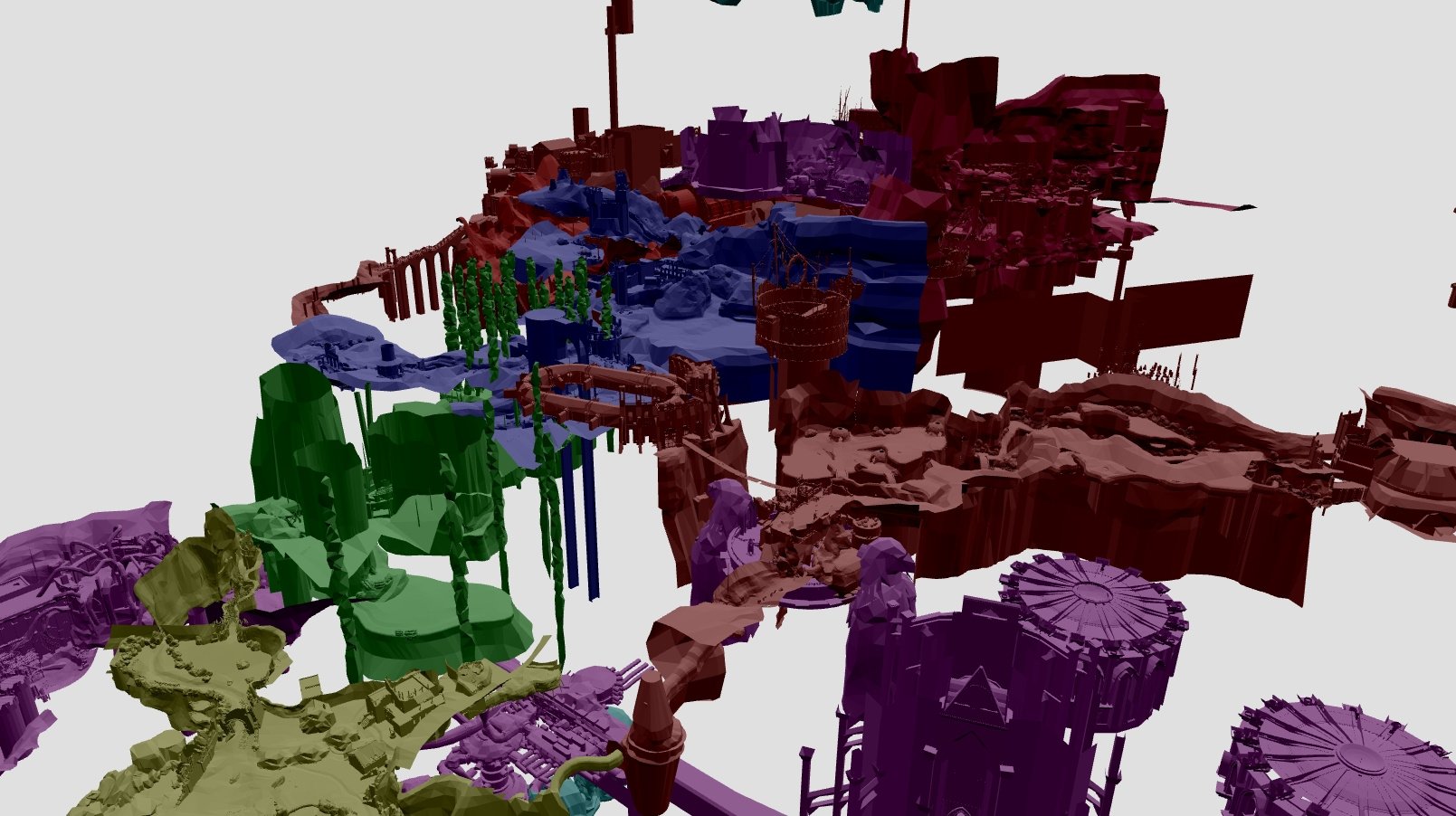

Set in a post-apocalyptic and oppressive world, Dark Souls presents almost no soundtrack for the entirety of the experience − except for some rare and dramatic enemy encounters. Instead, its sound design leaves space for immense and disturbing silence, made of wind blowings and distant inhuman screams, to narrate a sensation of a calm eeriness and standing in opposition to the high action rate of the title.

Dark Souls and other games from the development company “From Software” are based on the concept of lore as a method of world-building, which uses a mixture of different and indirect hints spread in the background of the game’s scenario to communicate the narration. For example, the Lovecraftian narrative of Bloodborne (2015) is reproduced also through sound design which transmits hidden events from the main story arc just by using some peculiar sonic elements, like the chants of certain creatures or an unknown cry.

Dark Souls and other games from the development company “From Software” are based on the concept of lore as a method of world-building, which uses a mixture of different and indirect hints spread in the background of the game’s scenario to communicate the narration. For example, the Lovecraftian narrative of Bloodborne (2015) is reproduced also through sound design which transmits hidden events from the main story arc just by using some peculiar sonic elements, like the chants of certain creatures or an unknown cry.

In the game design method adopted by the company, sound design becomes one of the main vehicles for the representation of a work as an environment: through the use of an indirect sonic narration, made of background elements, is possible to create a more immersive, liquid and singular experience.

In this sense, Dark Souls and Bloodborne follow a rhizomatic approach in the creation of a game experience, in which there are no direct inputs/outputs or grades of relevance between the different objects that compose the game design of such products. Everything is flattened, everything is moved to the background, everything is in the hands of the player and it can decide how to be affected by that narration. “From Software” uses the standard laws and codes of RPG and gamebooks and brings them to an extreme level of interaction.

In a certain sense, this system partially follows what theorist Monika Fludernik defines as experentiality of narration, in which the entirety of the experience is triggered by a series of cognitive parameters present in the composition of a game narrative, like the consciousness of intentional actions and the emotional value of a determinate object − for example, the infamous and semi-human Cleric Beast’s scream and its impact on the community.

Speaking about affection and experentiality in terms of sound, one of the most remarkable texts on this topic is Sonic Warfare (2009) by theorist and musician Steve Goodman, aka Kode9. The core of the book is an analysis of the affective feature of sounds as a weapon through a series of examples that goes from historical events, deconstructed philosophy, to club culture. Sound works as a tool able to create repulsive or attractive forces that push people in the creation of new environments − both cultural and spatial.

Speaking about affection and experentiality in terms of sound, one of the most remarkable texts on this topic is Sonic Warfare (2009) by theorist and musician Steve Goodman, aka Kode9. The core of the book is an analysis of the affective feature of sounds as a weapon through a series of examples that goes from historical events, deconstructed philosophy, to club culture. Sound works as a tool able to create repulsive or attractive forces that push people in the creation of new environments − both cultural and spatial.

Steve Goodman highlights in particular one of the tactics deployed by US soldiers during the Vietnam War, which involved the use of reverberated and distorted audio recordings of human laments and screams reproduced through speakers. This strategy was used as a psychological weapon that subliminally attacks the beliefs of the Vietnamese population and creates the illusion of ghost presences on the battlefield. The legacy of such affective phenomenon is detectable in the game-changer masterpiece Death Stranding (2019) by visionary designer Hideo Kojima, which presents a unique use of sound as a psychological tool. The whole plot of the game revolves around the concept of death and the emotional connections between individuals, using an innovative approach that granted Death Stranding a series of awards in the field of the arts. Apart from the stunning soundtrack that directly plays with the emotional value of the audience in some of the most memorable moments in the history of the game medium − making Death Stranding a product that becomes one of the greatest attempt to create an immersive and interactive cinematographic experience − the sound design section works on a deeper level of affection. The use of sound as a psychological weapon is particularly enhanced in a segment of the game set in an illusory Vietnamese battlefield, in which the protagonist is surrounded by haunting presences that melt together within the deafening sounds of war. Such presences are reproduced by using the same affective tactics reported by Steve Goodman in Sonic Warfare, reproducing the sound of ghostly screams that run from a speaker to the other.

The choice of using a sonic strategy that has such an affective impact on the listener and is linked with an unearthly plan of existence − the invisible spiritual world, inhabited by the deads – represents a precise narrative expedient in Death Stranding. The whole conceptual environment is based on lost connections between people, whether they be living or dead − some visual object like umbilical cords, ladders, bridges, and other “connective tools” are recurrent in the game − and the use of such sound design links not only Death Stranding with a real historical event but also enhances the relational concept with the world of the “unseen”. Sound becomes an active part of lore by connecting conceptual, visual and narrative elements together.

Moreover, it is to be considered that Sonic Warfare revolves around the idea of connecting and repulsing people through sound, so the audio choices of Hideo Kojima must not be taken as merely casual and aesthetical.

Game design is becoming an instrument of world-building by its own, and it’s capable of using its elements in brand new modes, far from a purely visual, audio or performative manner. As I already wrote, the creation of an environment is a method of production able to erase codes and languages that can arrest the development of new artistic outputs. The liquid behaviours of sound and game design work as a catalyst for different objects, chronological events and unusual references; there’s compelling evidence that more and more artists and theorists are analyzing components and instruments coming from such fields in their works. This is due to the ability of sound and game design to merge disparate elements together to build a concrete narration, or in other words, an environment.

Game design is becoming an instrument of world-building by its own, and it’s capable of using its elements in brand new modes, far from a purely visual, audio or performative manner. As I already wrote, the creation of an environment is a method of production able to erase codes and languages that can arrest the development of new artistic outputs. The liquid behaviours of sound and game design work as a catalyst for different objects, chronological events and unusual references; there’s compelling evidence that more and more artists and theorists are analyzing components and instruments coming from such fields in their works. This is due to the ability of sound and game design to merge disparate elements together to build a concrete narration, or in other words, an environment.

Game directors, for their parts, are challenging the way in which sound is perceived and experienced. The role of audio as a pure background or accompanying element in a game is slowly disappearing in favour of a more avant-garde approach, not only on a technological side but also as a conceptual one.

Our times need a reconsideration of the game medium as one of the most valuable tools of innovation and affection in the art field; its ability to affect external territories and push their features to the edge to create unexplored narratives represents, in my opinion, what contemporary artists must actually pursue.

Listen to the playlist featuring some of the most engaging game soundtracks of the last generations, from hauntological j-rock and deafening orchestras, to dreamy lullabies and folk ballads.