Disclosure #04 | Arseny Zhilyaev

Disclosure is a focus on the artist’s studio, considered both as a place of physical and intellectual production and as an archive of languages and experimentations. The project, with photographs by Riccardo Banfi and interviews by Giulia Morucchio for Cactus Magazine, features artists based in Italy who work with heterogeneous media and practices. In the fourth episode, we went back to Venice. We had a chat with Arseny Zhilyaev, a conceptual artist based between Moscow and Venice who works at the edge of fiction and non-fiction creating imaginary museums and exhibitions.

Disclosure is a focus on the artist’s studio, considered both as a place of physical and intellectual production and as an archive of languages and experimentations. The project, with photographs by Riccardo Banfi and interviews by Giulia Morucchio for Cactus Magazine, features artists based in Italy who work with heterogeneous media and practices. In the fourth episode, we went back to Venice. We had a chat with Arseny Zhilyaev, a conceptual artist based between Moscow and Venice who works at the edge of fiction and non-fiction creating imaginary museums and exhibitions.

Arseny Zhilyaev (Voronezh, 1984) is a Russian artist who has chosen the exhibition and, more generally, the museum as his ideal medium.

Arseny Zhilyaev (Voronezh, 1984) is a Russian artist who has chosen the exhibition and, more generally, the museum as his ideal medium.

His artistic production is linked to the study and recovery of Russian culture and cosmism. In particular, Zhilyaev is interested in the theories, elaborated by the philosopher founder of cosmism Nikolai Fedorov, on the role of museology and art in the construction of the ideal society. Indeed, Fedorov argued for the centrality of the art museum as a fundamental means of social and human development. Starting from cosmism, Zhilyaev’s reflections then extended to the study of museological theories that influenced the debate on art following the Russian revolution. This practice led him to revisit and re-actualise some experimental museum projects of the 1920s and 1930s, such as the complex Marxist experimental exhibitions created by Aleksei Fedorov-Davydov. The archival yet fictional materials he collected were later published in an anthology entitled Avant-Garde Museology (e-flux Classics, 2015).

In addition to experimenting with the institutional framework, one of the key features of his projects is their fictional and futurological drive. He positioned his exhibitions in an imaginary future reflecting on the present (see in this regard, The Museum of Proletarian Culture, M.I.R.: New Paths to the Objects and M.I.R.: Polite Guests from the Future). By engaging with the exhibition-making machinery and using the temporal distance, he critically explores the current state of the art and society’s status quo. Among his most recent works is the Institute for Mastering of Time (IMT), a project inspired by the book Mastering Time as the Main Task of Organization of Labor by the Russian philosopher Valerian Muravyov. This organization seeks to enhance the historical continuum condensing as much time as possible through the optimization of the past. IMT’s scientific research focuses ⎯ through workshops and training sessions ⎯ on accelerating the development of art, pushing the artificial forward to its limits, the museification of the Earth and the Universe, the maximum possible increase in the pace of artistic production, and the transition from an institutionalized modus operandi to that of teams or brigades. In Zhilyaev’s artistic production, the quest for immortality derived from cosmism appears transposed in the search and assembly of data to create new networks of meaning. From these actions the desire for immortality, at least authorial, becomes evident.

We caught up with Zhilyaev in his house in the sestiere Castello, Venice, with his wife Katia and their toddler Lev.

Giulia Morucchio: You are a post-studio artist living between Moscow and Venice, not bound to a specific working space or environment. What are the pros and cons of this methodology? Generally speaking, which conditions influence your creative and productive needs?

Giulia Morucchio: You are a post-studio artist living between Moscow and Venice, not bound to a specific working space or environment. What are the pros and cons of this methodology? Generally speaking, which conditions influence your creative and productive needs?

Arseny Zhilyaev: I work with museums and exhibitions as the ultimate mediums of expression in the territory of contemporary art. In practical terms, it led to new ways of artistic production for each new project which resulted in abandoning the permanent working space and cut my practice mainly to a laptop and table. Only about a year ago, I had the opportunity to build a studio at my dacha in the Moscow region. It is used for big projects. So, the studio in my case is mainly something in between a warehouse and a space for thinking.

In Venice, I’m doing a series of works that do not require a lot of space. These are mainly chamber “drawings” related to my research inside the “Institute for Mastering Time.”

In terms of work conditions, I grew up in a not very artistic environment and I elaborated a special mood of perception of reality split between my inner working processes and the almost entirely independent outside world.

GM: You have often worked on large-scale projects. Where and how do you store and archive them?

GM: You have often worked on large-scale projects. Where and how do you store and archive them?

AZ: From a formal point of view, I continue the tradition of total installation proposed by Ilya Kabakov, and one of the main problems with such a thing is storage. Even in the case of Kabakov’s installations, museums would throw away everything that didn’t bear the marks of his hands, like wallpapers, old floorboards, rubbish, etc. But since this is the heart of the work, what creates the atmosphere and the general impression, he was essentially required to make the work from scratch at each exhibition. As a result, Kabakov ⎯ who is very sensitive to the museum as a technology that ensures the artist’s immortality ⎯ almost completely focused on painting because it is easier to care for and archive.

Needless to say, most of the installations by less significant artists were sent to the scrap heap almost immediately after the exhibitions, but sometimes even that was not possible. For a long time, I lived and exhibited in Moscow squats located inside former factories. I had almost no money, and the removal of garbage from the industrial zone in Moscow had to be paid separately. As a result, together with my colleagues, we literally had to scatter our art through the streets of Moscow at night. Fortunately, some of my early pieces survived because they were given to museums or foundations.

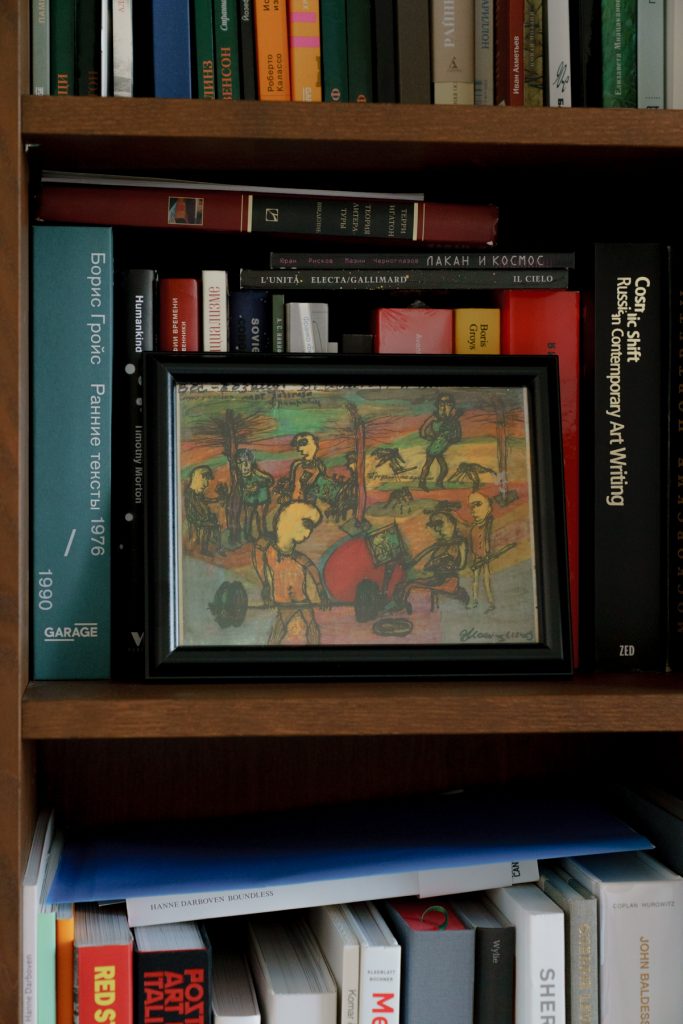

GM: In your apartment in Venice, you have artworks by other artists ⎯ like the one by Mark Dion with whom you did the exhibition Future Histories at Casa dei Tre Oci (Venice) in 2015 or by Russian artists Anatoly Osmolovsky, Pavel Pepperstein and Valery Isayants.

GM: In your apartment in Venice, you have artworks by other artists ⎯ like the one by Mark Dion with whom you did the exhibition Future Histories at Casa dei Tre Oci (Venice) in 2015 or by Russian artists Anatoly Osmolovsky, Pavel Pepperstein and Valery Isayants.

You also have a golden stone, part of one of your previous installations realized during an artist residency at Headlands San Francisco, USA.

Since the exhibition format is your medium of choice, I was wondering if there is a criterion behind this private collection and how you displayed it.

AZ: No, this is a random selection of works by artists. I worked with some of them, such as Mark Dion, who is a brilliant person, researcher and museum enthusiast, methodologically close to my artistic practice. Pavel Peppertstein, a Moscow conceptualist, is a friend to my family. Anatoly Osmolovsky is a crucial figure of the older generation from my formative point of view. Valery Isayants, on the other hand, is important in terms of memory and the places where I grew up. He was a poet and “naive artist” from Voronezh, my hometown. He was a strange fragment of late Russian modernism who was forgotten and spent the last 30 years of his life on the street.

Another significant piece I have in Venice is the book Moscow Portraits by former Yugoslav conceptualist Goran Đorđević, which contains a collection of “portraits” (mainly conceptual and abstract pictures by Yugoslavian underground artists). Goran is a technical assistant at the Museum of American Art in Berlin, the institution working forward de-artization, which is very close to what I am doing.

As for my works, there are many fragments in the house that, for some reason, stayed with me in Italy.

GM: Giving this interest in museology, how did you shape your recent projects on rave culture held in Portugal and Poland?

GM: Giving this interest in museology, how did you shape your recent projects on rave culture held in Portugal and Poland?

AZ: I create installations as imaginary exhibitions averaged in the future, and for some time now I have also been exploring role-playing games (LARP). In these collaborative projects, which often go under the heading “Institute for Mastering Time,” I invite colleagues to implement them. IMT owes its name to Valerian Muravyov, a cosmist who proposed to master time through “universal production mathematics,” that is, to remove time from our life as a significant and tragic factor. In addition to scientific works, Muravyov wrote fiction. In particular, he was planning an unwritten novel about the radio ant uprising. One of the chapters of this text formed the basis of the recent performance Honoring Faf and Tselar at Galleria Foco, Lisbon, and Goyki3, Sapot (Poland).

It consisted of a sort of rave in an underground laboratory, but with some elements of a museum display. In a nutshell, it is an experiment about zooming in time and transferring entropy from our version of reality to the one where the intergalactic revolution of radio ants won.

GM: On your table, there’s a CCCP rocket-shaped souvenir. Its presence, which refers to the Soviet myth of space, leads me to ask you about your interest in Russian cosmism with your research.

GM: On your table, there’s a CCCP rocket-shaped souvenir. Its presence, which refers to the Soviet myth of space, leads me to ask you about your interest in Russian cosmism with your research.

AZ: For the last 6-7 years, I have been working on Russian cosmism as an intellectual framework for my museological experiments. This is an umbrella term for a corpus of philosophies, artistic projects, theological speculations, and scientific theories that aim to achieve victory over death and devise a technology that provides resurrection and resettlement in outer space. I worked a lot on the topic together with Anton Vidokle, one of the founders of e-flux. But the theme of cosmism in Russian culture has deep roots. It is believed that it influenced the avant-garde; there is even Boris Groys’s interpretations of Malevich’s black square as an image of the black emptiness of the cosmos. You can find traces of the father of cosmism, Nikolai Fedorov (1829-1903), for example, in the work of one of the brightest soviet avant-garde writer Andrei Platonov, my compatriot from Voronezh. Even among Moscow conceptualists, the issues raised by Fedorov occupy an important place; in addition to Kabakov, whom I mentioned earlier, one can single out the works of the duo Elena Elagina and Igor Makarevich. To everyone interested in the reception of cosmism on the territory of art, I refer to the English publications by Italian researcher Alessandra Franetovich and philosopher Marina Simakova, who is also in Italy because of a research fellowship in Florence.

GM: A large part of your artistic production takes the form of publications. I am thinking about the books Avant-Garde Museology (2015) and Art without Death: Conversations on Russian Cosmism (2017), both edited by e-flux. Can you tell us more about your writing practice?

GM: A large part of your artistic production takes the form of publications. I am thinking about the books Avant-Garde Museology (2015) and Art without Death: Conversations on Russian Cosmism (2017), both edited by e-flux. Can you tell us more about your writing practice?

AZ: I write from time to time in a more theoretical mood. But it is not systematic writing and research. I feel more confident in fictional, poetical, or technical texts that reframe my exhibits within different versions of our universe. Meanwhile, together with V-A-C Foundation, I published some books in Venice with Marsilio Editori. Specifically, the catalogue Museum of Proletarian Culture: Industrialization of Bohemians (2013) and Pedagogical Poem. Archive of Future Museums of History (2014), edited in collaboration with Iliya Budraitskis.

GM: Your works often address the theme of the future through the filter of fiction, to talk about the current state of things and the art world. How do you see the future of art and artist?

GM: Your works often address the theme of the future through the filter of fiction, to talk about the current state of things and the art world. How do you see the future of art and artist?

AZ: It seems that the heart of “creativity,” which will replace art in the future, is the dialectic between automation and what cannot be automated (for example, in theory, the very desire of art to go beyond all automated rules constantly). And there is a lot here.

In terms of cosmism, automation frees up time. We may dream of automation as something that will give us the opportunity to create an archive of the future history of art and thereby free a person from its negative pressure. This transition can be compared with the invention of photography, which revolutionized the understanding of the aesthetics. After photography, mimesis ceased to be an intrinsically valuable and a completely defining art category.

After automation and liberation from the history of future art ⎯ which will be given to the market at this stage ⎯ fixation on novelty will take its well-deserved place in the fetish museum.