Exercises of Seeing | Hudinilson Jr.

This focus will be the first of a series of investigations around the theme of montage in contemporary culture. The series is conceived as an “exercise of seeing,” echoing a definition that Brazilian artist Hudinilson Jr. (1957-2013) used for his scrapbooks named Cadernos de refêrencias. To these, and the tactics adopted to move within Hudinilson Jr. ‘s montages, this opening excursion will be dedicated.

This focus will be the first of a series of investigations around the theme of montage in contemporary culture. The series is conceived as an “exercise of seeing,” echoing a definition that Brazilian artist Hudinilson Jr. (1957-2013) used for his scrapbooks named Cadernos de refêrencias. To these, and the tactics adopted to move within Hudinilson Jr. ‘s montages, this opening excursion will be dedicated.

Montage will be used as a tool and a weapon for understanding the body and the self in the post-modern and contemporary era. Moreover, it will also frame the space of our experience. Quoting Martino Siegli’s Montage and the Metropolis (2018), we can think of montage as the symbolic form of modernity: “As much as perspective established a system of spatial representation for early modern Western art that encapsulated an entire worldview, montage became defining for Western visual culture in the twentieth century. The Renaissance notion of a continuous and homogeneous space was replaced by the modern notion of discontinuous and heterogeneous one.”

We will cross this fragmented space as if we were engaged in a peripatetic action: walking, Michel de Certeau reminds us, means being in search of a space of one’s own. Through this practice we will try to make all the (theoretical) objects we meet along the way shine.

The term exercise again emerges as important here. Promoting the idea of a process aimed at the maturation of new knowledge, it will therefore help to question the use and role of montage in the different case studies analyzed.

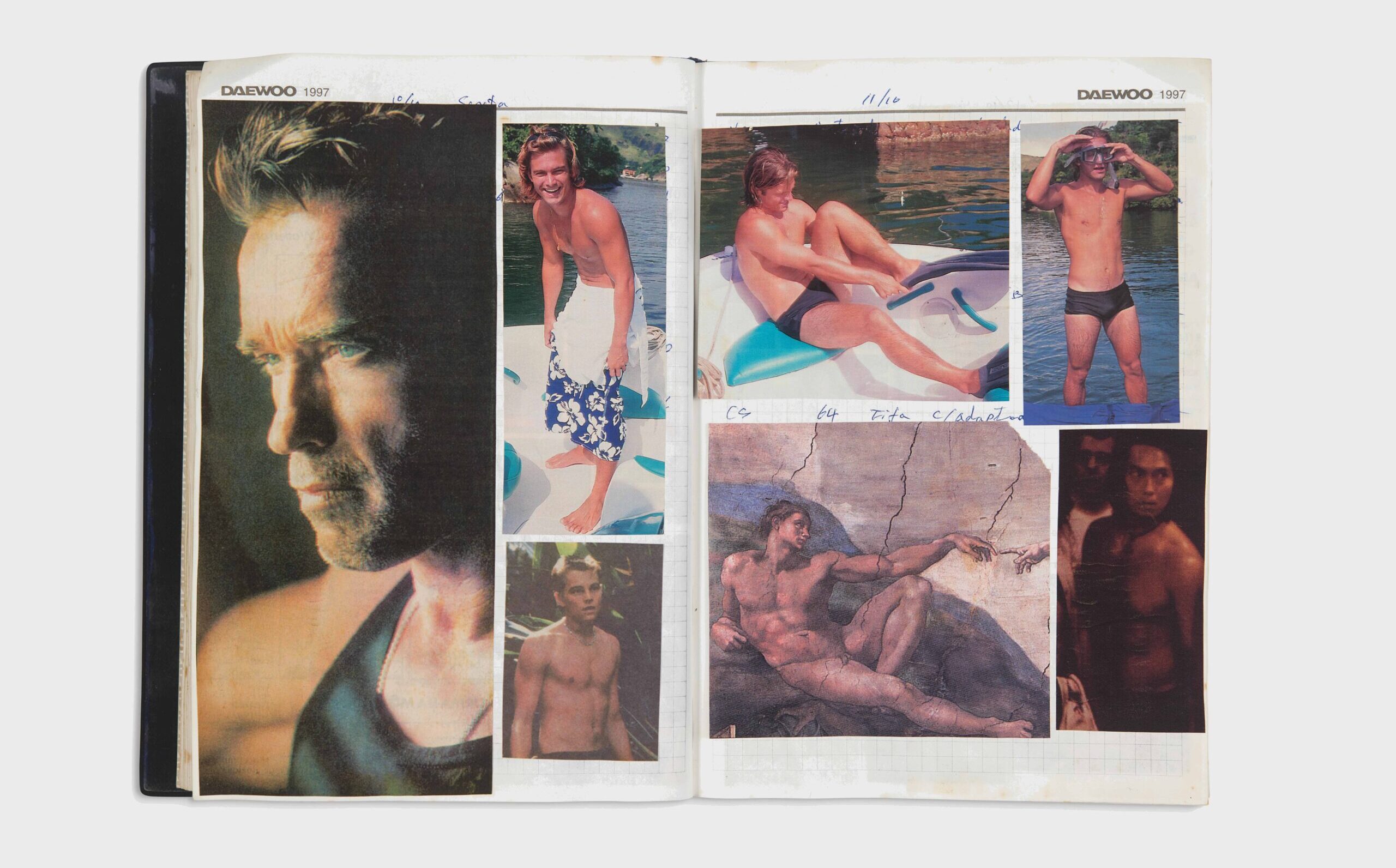

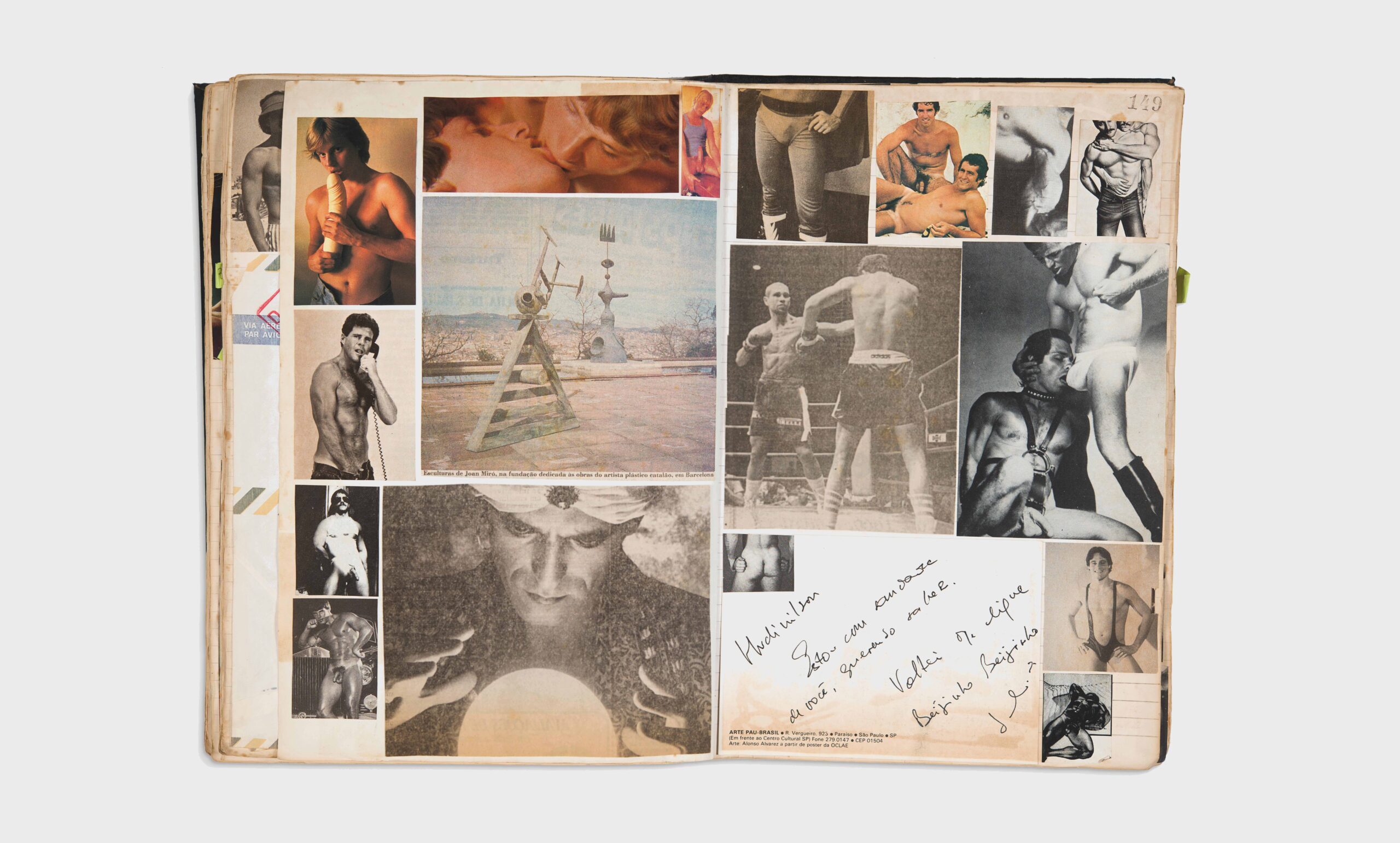

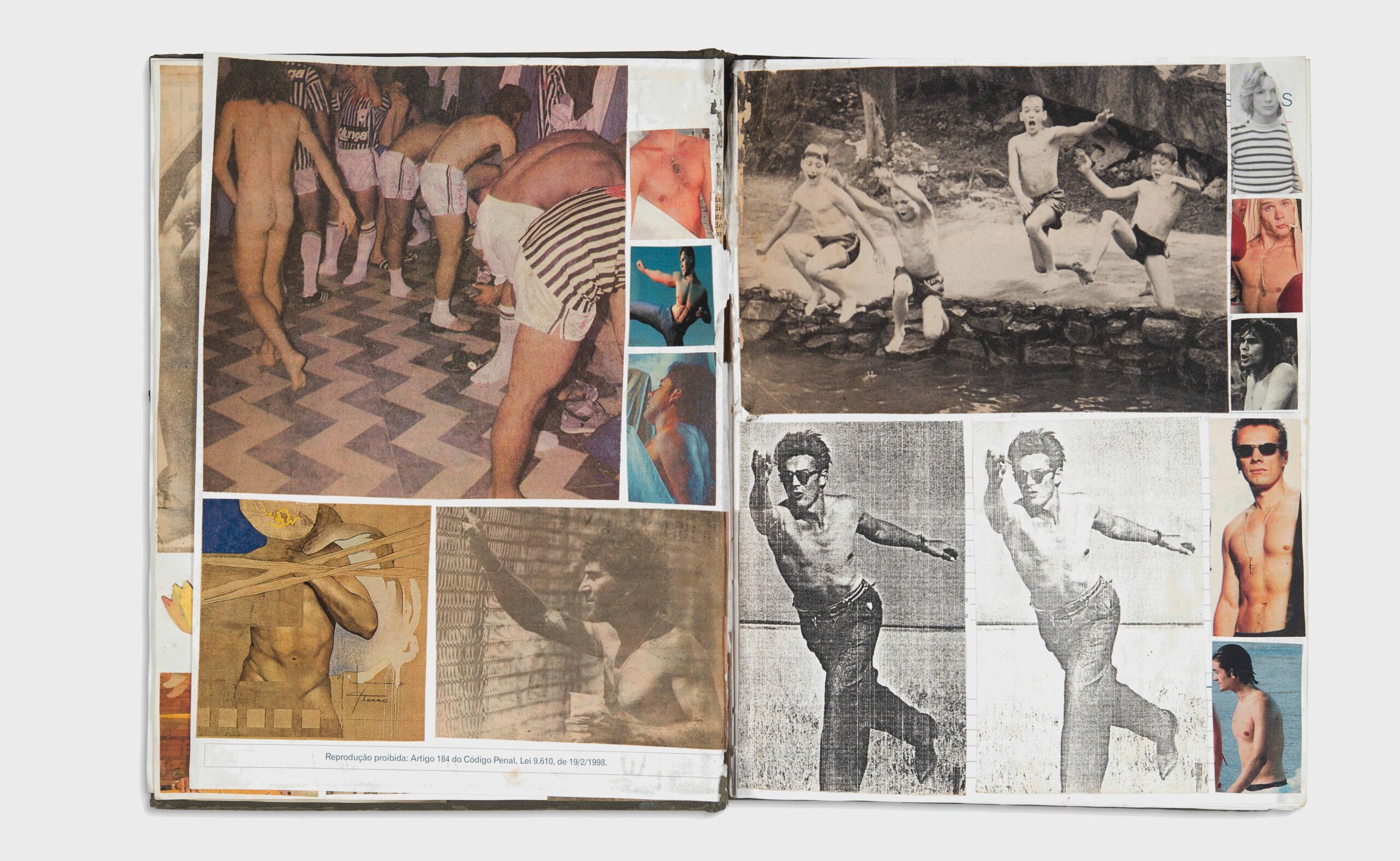

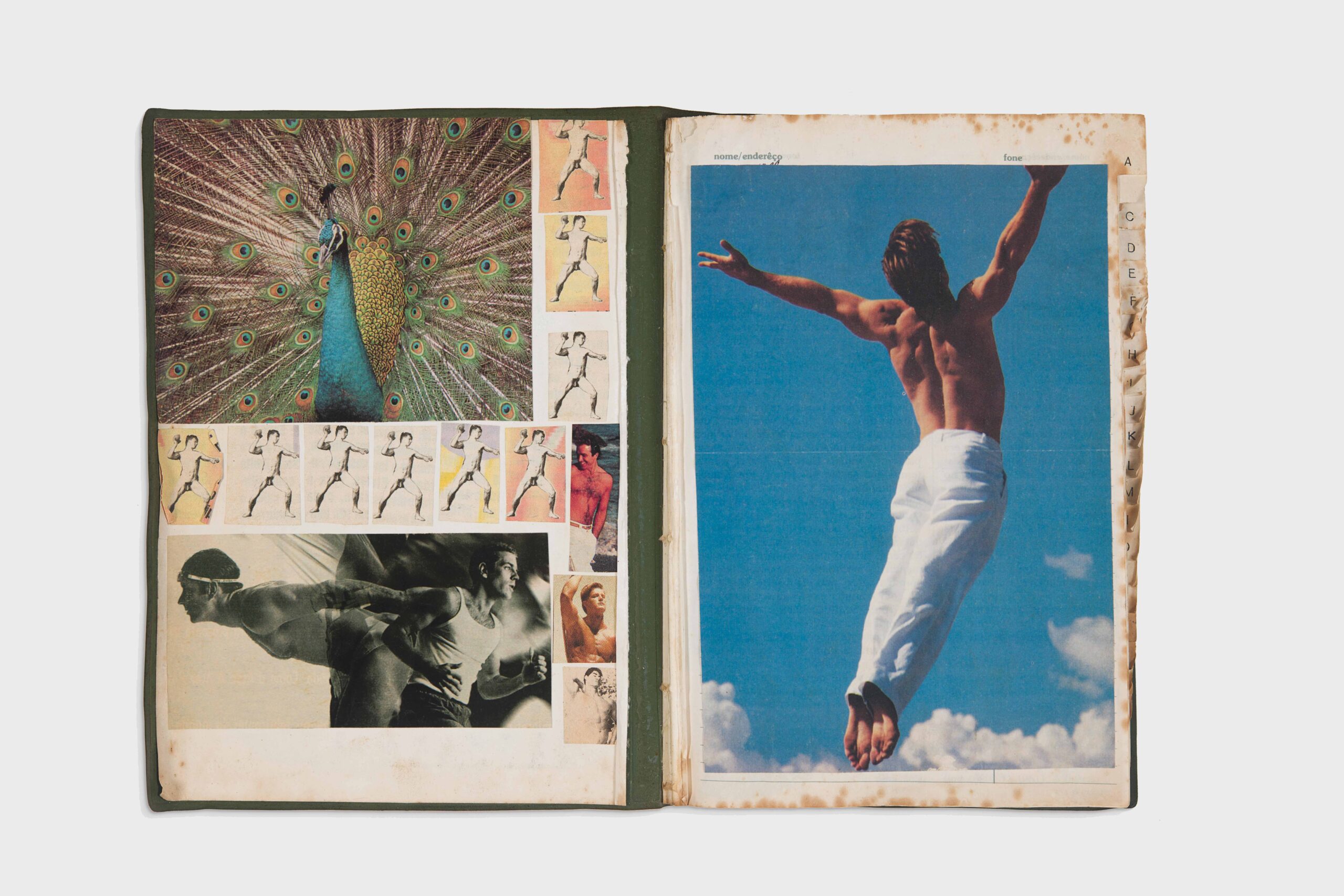

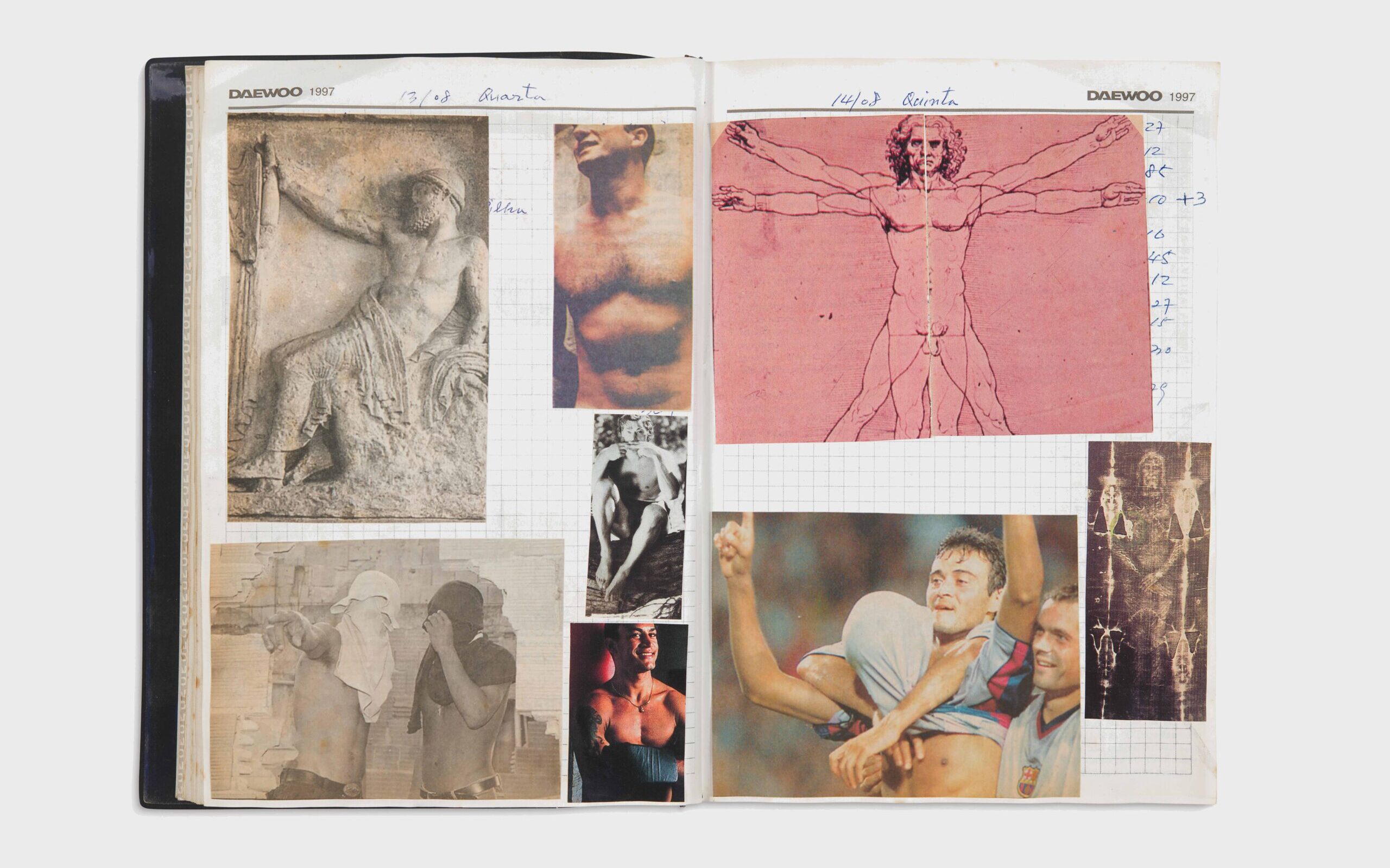

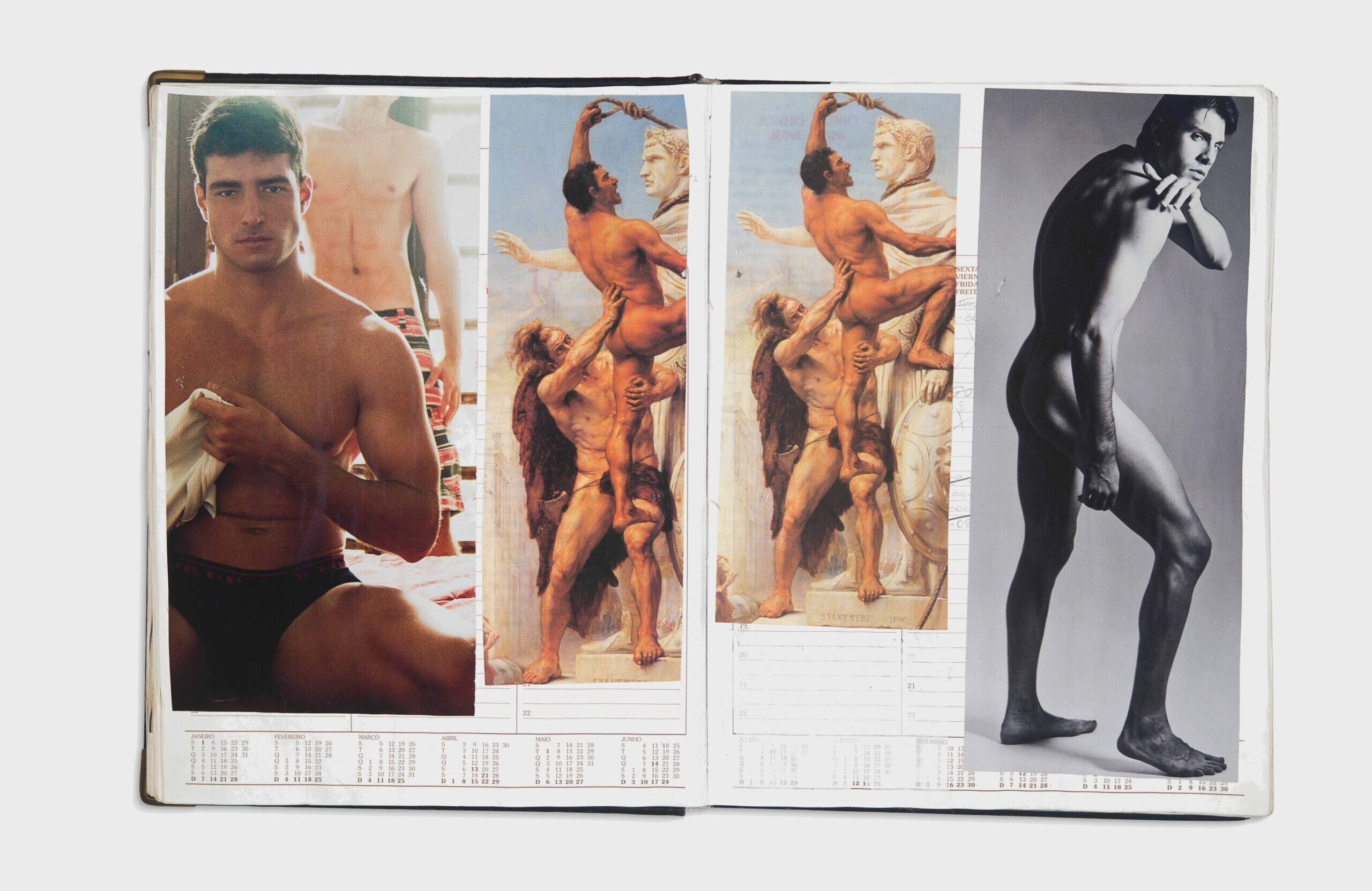

In Hudinilson Jr.’s practice, montage has a fundamental value. Although up to now the Cadernos have been largely understood as collage, let’s try to make a slight shift, replacing the word collage with the concept of montage. This is mainly for two reasons: first, the focus will be placed on the dialectical juxtaposition of elements rather than on the technique of manual assembly; second, the notebooks are studied as visual media, considering them not primarily aesthetic objects but images for reading, favoring an investigation of imaginary and remediation rather than tactile perception.

The use and reuse of materials from visual and mass media culture in Hudinilson Jr.’s work is extraordinary. Xerox images of Roman statues are juxtaposed with South American imagery, glossy pornographic images from Western magazines meet faded Brazilian newspapers. What interested him all his life was the image of the male body.

Deeply influenced by Jean Genet’s masturbatory wanderings, Hudinilson Jr. soon realized that Narcissus could become a symbol, a guiding identification for his practice. Narcissus for the artist never dies, peregrines among the images of this world. Ricardo Resende, in Posição Amorosa (2016), the first and only complete monograph dedicated to the artist, explains the theme in this way: “Hudinilson’s Narcissus is made eternal through his own image and through the hegemonic and hedonist images he gathered. A countless amount of images that integrate and complement his imagetic archive-work.”

Deeply influenced by Jean Genet’s masturbatory wanderings, Hudinilson Jr. soon realized that Narcissus could become a symbol, a guiding identification for his practice. Narcissus for the artist never dies, peregrines among the images of this world. Ricardo Resende, in Posição Amorosa (2016), the first and only complete monograph dedicated to the artist, explains the theme in this way: “Hudinilson’s Narcissus is made eternal through his own image and through the hegemonic and hedonist images he gathered. A countless amount of images that integrate and complement his imagetic archive-work.”

The myth of Narcissus deals with an overwhelming impulse, which can be synthesized through the exhortation “gnothi sautón” [Know thyself] inscribed on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. This maxim would be the backdrop for all of Hudinilson Jr.’s work. He interpreted it through a scopic and performative investigation of the body, both personally, through Xerox Actions, his most famous practice, and through a tireless work of collecting images that shaped his reference notebooks.

In late 2020, Ana Maria Maia curated, at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Explícito, the latest Hudinilson Jr.’s solo show. The exhibition was an opportunity to reinforce the intense relationship that has bound the artist to the city through the many works of public engagement that have marked his practice, from graffiti, billboards, to urban interventions. But it was also a chance to valorize the artist’s obscene, pornographic, countercultural value. Continuing the important work of rehabilitation that began, among others, with Resende’s monograph and Fernanda Nogueira on-going research on southern artistic pornographies, Maia succeeds in preserving the heuristic power of the notebooks by not reducing them to simple archives or artist’s books. In the dedicated catalogue, she underlines the profoundly anachronistic nature of the visual montages of notebooks; and she explains how the chronological breaks characterized not only their creative process but also their thematic composition, turning them into a device for cross-cultural revision.

Now, even if it would be necessary to dedicate ample space to the support that hosts these montages, and to the theme of the atlas-form, I will only be able to mention them here, to then immediately frame more closely the peripatetic action that moves this research and that here finds its declination in the practice of cruising.

Now, even if it would be necessary to dedicate ample space to the support that hosts these montages, and to the theme of the atlas-form, I will only be able to mention them here, to then immediately frame more closely the peripatetic action that moves this research and that here finds its declination in the practice of cruising.

Treating these scrapbooks as atlases means considering them as operative machines able to activate an analytical space that allows for a renewed reading of the images. Examined not as a unity, but as structures based on relation and collision, the images in this way continually question their semantic and pathos stability.

Built on montage and on an iconology of the interval, for Georges Didi-Huberman a paradigmatic example of an atlas is Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne. It would be fascinating to compare the gazes that these two ‘hyperimage machines’ are capable of fabricating. At first glance, the syntax that informs Hudinilson’s notebooks appears much more cinematic, made of shots and countershots, closeups and eye contacts.

However, what needs to be emphasized here is not primarily the construction of the gaze of Hudinilson’s notebooks. What is relevant here is to suggest a way of reading and practicing these notebooks. And I would like to think, if only as a provocation, that this “wandering practice” moved the artist’s gaze as well. After all, if the curators of the Cruising Pavilion at the 16th Venice Biennale of Architecture said that “cruising is the powerful human smell that haunts the dreams of Jean Genet,” why not think that cruising also haunts Hudinilson’s thoughts?

I would like here to take up the metaphor that Andrew Berardini uses in the essay published on Mousse 12 about the Los Angeles-based artist Richard Hawkins to state: Hudinilson Jr. as an artist is cruising. As Berardini recalls: “Cruising is a prolonged look of lust, forcing the eyes to linger. Cruising is never going anywhere in particular, but open to opportunity as it may present itself (or himself as the case may be). […] When and where it entered the gay lexicon is unclear, but the word […] matches the act of being open, the danger and adventure of sex with a stranger, the hard history of men resorting to dark, anonymous couplings because of the taboos associated with their desire. Cruising has a nomadic restlessness pulled along by the imperative of desire.”

I would like here to take up the metaphor that Andrew Berardini uses in the essay published on Mousse 12 about the Los Angeles-based artist Richard Hawkins to state: Hudinilson Jr. as an artist is cruising. As Berardini recalls: “Cruising is a prolonged look of lust, forcing the eyes to linger. Cruising is never going anywhere in particular, but open to opportunity as it may present itself (or himself as the case may be). […] When and where it entered the gay lexicon is unclear, but the word […] matches the act of being open, the danger and adventure of sex with a stranger, the hard history of men resorting to dark, anonymous couplings because of the taboos associated with their desire. Cruising has a nomadic restlessness pulled along by the imperative of desire.”

In Hudinilson both content and practice seem to be cruising. Restless. The reader of Cadernos thus lies in a position suspended between indulging the strong scopic drive typical of the voyeur and the peripatetic cinematic movement typical of the voyageur. These two reading practices, if not meeting, move together hand in hand.

In 2001, preparing the performance Narciso revisita seus espelhos [Narcissus revisits his mirrors] at the Mercosul Biennial, Hudinilson Jr. spoke of himself as an image hunter. The endless hunt for representation and reproduction of the male body that guided the artist throughout his life unites and at the same time opposes him to the destiny of Narcissus: is it not precisely after a hunt that the tired and thirsty young man goes to the source and loses himself in the illusion of the image?

Hudinilson Jr. began to enjoy international attention only after his passing. The re-evaluation of his work has only recently begun and is still to be explored, especially for its subversive potential: the investigation of masculinity and its new postures in the queer and cultural studies arenas.

Hudinilson Jr. began to enjoy international attention only after his passing. The re-evaluation of his work has only recently begun and is still to be explored, especially for its subversive potential: the investigation of masculinity and its new postures in the queer and cultural studies arenas.

From the early 1980s until his death, Hudinilson Jr. used notebooks to grab the visual environment that intrigued him and from which he was informed daily. He didn’t take photos, he collected fragments. By cutting and pasting images from magazines, newspapers and ephemera, cropping pictures from art history books and combining them with personal and friend photographic reproductions, Hudinilson Jr. impressed on paper the drives and visual thoughts of an entire life. His environments were made of bodies, male bodies full of erotic tension and identity research, such as to problematize not only the forms of heteropatriarchal desire but also those of queer representation.

Let’s conclude by introducing a final vertigo. Or at least enter an expanded constellation of images. Thinking about artistic scrapbooks and the influence of Jean Genet on the culture of the second half of the 20th century, Tatsumi Hijikata’s Butoh performance art genre and his 1960s and ’70s Butoh-fu scrapbooks sprang to mind. Later, I discovered that these same scrapbooks were the inspiration for Richard Hawkins’ Ankoku series. In 2012, talking about his work in the Whitney Biennial, Hawkins claimed: “I also found it interesting that Hijikata hardly ever used Japanese artists or figures in his scrapbooks. Rather, he was always exoticizing French and American culture. It’s Orientalism in reverse. Maybe through all this I’ll finally figure out why my objects of desire hardly ever come from my own damn culture.”

To the triangle formed by France, America and Japan, at this point it is worth adding two new coordinates to create with Brazil and the Mediterranean cultural area a pentagon always ready to change shape. Moving forward, all that is needed is to bring Hudinilson Jr., Richard Hawkins, Jean Genet, Tatsumi Hijikata, and Narcissus together, not necessarily by placing the West at the center, but by drawing a trajectory that intercepts all points simultaneously, as in a flash.