Exercises of Seeing II | The Lonely Man

This focus is dedicated to the screenings that premiered at the 78th Venice International Film Festival and aims, through a montage exercise, to reveal a leitmotiv that links many of the narratives presented. Indeed, a common theme, sometimes more hidden, sometimes more explicit, seems to characterize the contemporary vision: the crisis of masculinity; or rather: the lonely man and his detachment from relationships.

This focus is dedicated to the screenings that premiered at the 78th Venice International Film Festival and aims, through a montage exercise, to reveal a leitmotiv that links many of the narratives presented. Indeed, a common theme, sometimes more hidden, sometimes more explicit, seems to characterize the contemporary vision: the crisis of masculinity; or rather: the lonely man and his detachment from relationships.

This year’s festival was full of films that presented visibly harmful and poisonous models of masculinity, highlighting all sorts of patriarchal stereotypes and militaristic upbringing where tenderness and feelings are silenced or raped through passive aggressive attitudes that mock their nature. The topic is a hot one. The male as we have widely known him is over. Even in the most mainstream western cinema we can now see the consequences of a widespread intercultural climate that has so far remained socially underground and academically clandestine ⎯ finding strong resistance in the political and institutional system ⎯ but which for at least fifty years has critically addressed male subjectivity in order to rethink it. We mention only two major European exhibitions that have recently explored the theme to reflect on contemporary negotiations in terms of identity and gender: Maskulinitäten (2019) a tripartite exhibition between Bonn, Dusseldorf and Cologne interested in “questioning how a feminist exhibition on masculinity could look;” and Masculinities. Liberation through Photography (2020) at Barbican in London that considered “how masculinity has been coded, performed, and socially constructed from the 1960s to the present day.” Last but not least, Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear (2022), a forthcoming exhibition at V&A Museum in London (another notable show on men’s fashion has just closed in Brussels) that plans to “explore how designers, tailors and artists have constructed and performed masculinity, and unpicked it at the seams.”

In any case, it was a surprise newcomer who won this year’s coveted Golden Lion. The young French-Lebanese filmmaker Audrey Diwan triumphed with L’événement, a movie set in the 1960s that takes the viewer through the anguished experiences faced by Anne (Anamaria Vartolomei) when she decides to have an abortion (an illegal act at the time, but still sadly at the center of political and social debate in many countries), shortly before coming of age, from a pregnancy that is as unexpected as it is inappropriate. Anne’s cry of pain sweeps away all pretenders (the jury voted unanimously) bringing the body and its political relevance to center stage.

All around this powerful movie, we should make the effort to imagine a multitude of inebriated male figures dancing, like praying mantises, just like the bodies in Maurice Bejart’s magical, seductive and deadly choreography of Ravel’s Bolero. Hopelessly defeated but untamed, they pile up filling the whole space: they yearn for power for an outro of pure violent silence.

We find both in and out of competition many case studies that attempt to unwrap old anachronistic masculine models by exacerbating their traits in pursuit of new relational ecologies. The essay will assemble a bumpy path connecting different salient manifestations of masculinity in crisis for new stimulations. Like pieces of different puzzles put together, the filmic narratives will come together to create a disjointed form with more ruptures and cuts than unified coherence.

Let’s start with another abortion, symbolically different from L’événement, to open the puzzle. This is Scenes from a Marriage, the remake of Ingmar Bergman’s 1973 six-part television miniseries of the same name, written and directed by Hagai Levi.

Let’s start with another abortion, symbolically different from L’événement, to open the puzzle. This is Scenes from a Marriage, the remake of Ingmar Bergman’s 1973 six-part television miniseries of the same name, written and directed by Hagai Levi.

Jonathan (Oscar Isaac) is a professor at Tufts; Mira (Jessica Chastain) is a technology executive. They live near Boston. A graduate student in psychology is there at home to interview the couple for research on gender norms and monogamy in couples. The researcher tells Mira and Jon that the average American marriage lasts 8.2 years. They, having exceeded 10 years together, deserve to be included in the study. Indeed, it seems that couples in which the female partner earns more than the male partner, while also leaving the latter with extensive parental duties, are those in which the couple’s happiness is maintained the longest. Mira seems distracted and responds hastily. Only Jon is eager to talk about his marriage; he volunteered for the study to undo its premises, such as the rejection of the concept of “successful” marriage. He hates to think of marriage in terms of the marketplace. He sees marriage as a means for having children, feeling secure, pursuing meaningful work outside home. Mira prefers talking of “an equilibrium”. Their marriage is no longer very desirable. When the researcher finally asks them about their monogamy, a shy laugh is the only answer. They haven’t given it much thought. If self-abnegation seems natural to Jon, Mira is painfully repressing something that will soon be revealed. Can Jon imagine himself prey to desire?

The five-episode series is an endless dialogue between the two characters. Scenes from a Marriage is as much a love story as a divorce story. On the night of the interview, Mira reveals to Jon that she is pregnant and though initially reluctant, they decide to keep the baby. Jon in particular wants to keep it. His upbringing as an Orthodox Jew and his attachment to his daughter Ava, who had repeatedly expressed a desire to have a baby brother, convince him that it is the right thing to do. A few scenes later we find Mira swallowing an abortion pill. For her, the time is not right. Her career takes priority. Jon is against it but suffers in silence. Everyone remains alone in their rooms. Home is the third major protagonist of the series. The house as an active organism with its own function in the relational ecosystem. The whole series takes place in the house, in its different rooms, each with its own soundscape. The house transforms when relationships change. It absorbs their energy. Jon, left by Mira, moves downstairs, sleeping in the same room as his daughter. He seeks comfort. Home, without his wife, becomes a nightmare too great to face. He holes up in his daughter’s room, a room still of dreams and caresses. He has nothing but her. Throughout the series he is deeply alone and tries to fill so much emptiness with words, and with Ava.

The father-son relationship is at the heart of many of the movies screened at the festival. Out of competition we find the second piece of the puzzle: Old Henry by Potsy Ponciroli. Wyatt (Gavin Lewis), son of a docile, quiet, very reserved, and widowed farmer (Tim Blake Nelson), is alone in the house with a wounded stranger in his bed. He finds his father’s rifle and begins to “man up” by firing a few shots here and there near the house. When he returns home the wounded man has untied himself and is waiting for him in an ambush that only his father, duly returned, can foil. Every time Wyatt tries to “become a man,” his masculinity assaults him, trying to steal his life. The father in his son’s eyes is the ultimate symbol of repression and distrust. The boy can’t wait to run away from home; he is naive but has an insatiable desire to see the world and get out of his corner at the edge of the forest. Old Henry harbors a deep secret that forced him to isolate himself from the world long ago, dragging his entire family into anonymity and remote solitude. The innocent son is unaware of the past. The geographical isolation in which they live coincides with the emotional isolation that fuels their relationship. Only the discovery that the dying father was actually the legendary Billy the Kid will reconcile them in extremis, finally redeeming a parental figure otherwise apathetic and severe, but perhaps the only one who had tried to repress a masculinity forged on violence and arrogance, without finally succeeding. The entire film is more interested in safeguarding the honor and father figure of Billy the Kid than in putting itself in the shoes of the young man who, however reckless, deserves much more trust, not only from his father but also from the director.

The father-son relationship is at the heart of many of the movies screened at the festival. Out of competition we find the second piece of the puzzle: Old Henry by Potsy Ponciroli. Wyatt (Gavin Lewis), son of a docile, quiet, very reserved, and widowed farmer (Tim Blake Nelson), is alone in the house with a wounded stranger in his bed. He finds his father’s rifle and begins to “man up” by firing a few shots here and there near the house. When he returns home the wounded man has untied himself and is waiting for him in an ambush that only his father, duly returned, can foil. Every time Wyatt tries to “become a man,” his masculinity assaults him, trying to steal his life. The father in his son’s eyes is the ultimate symbol of repression and distrust. The boy can’t wait to run away from home; he is naive but has an insatiable desire to see the world and get out of his corner at the edge of the forest. Old Henry harbors a deep secret that forced him to isolate himself from the world long ago, dragging his entire family into anonymity and remote solitude. The innocent son is unaware of the past. The geographical isolation in which they live coincides with the emotional isolation that fuels their relationship. Only the discovery that the dying father was actually the legendary Billy the Kid will reconcile them in extremis, finally redeeming a parental figure otherwise apathetic and severe, but perhaps the only one who had tried to repress a masculinity forged on violence and arrogance, without finally succeeding. The entire film is more interested in safeguarding the honor and father figure of Billy the Kid than in putting itself in the shoes of the young man who, however reckless, deserves much more trust, not only from his father but also from the director.

Out of competition we also find Stefano Mordini’s The Catholic School, a movie that tries (and in my eyes fails) to capture the rage and violence that lurks latently in the hearts of upper middle-class Roman boys in the mid-1970s, educated in a brutal and physical masculinity that constantly demands practical demonstrations of strength and supremacy. The holy power of command. The sons of the country’s ruling class soon turn into murderous rapists, suddenly overturning the good values with which, according to the system, they had been brought up. They find themselves slaves to a fierce masculinity that they could never renounce, this being the only gender expression they really knew.

A violent and criminal masculinity is likewise the subject of Lorenzo Vigas’ excellent La Caja. Hatzin (Hatzin Oscar Navarrete) insists on entering the life of what he believes to be his biological father (Hernán Mendoza), who denies any connection. Not yet fully aware of the kind of work his supposed father does, Hatzin keeps track of his expenses/income and reveals to him that he is paid less than he should be. The parent looks at him in astonishment. He, who lives by deceiving poor people, has himself been deceived without realizing it; and it is the most deceived creature of all ⎯ a little boy looking for his father ⎯ who warns him. Hatzin is all proud, he would even kill to keep his father out of trouble, but soon he must face reality. Although he does everything he can to elevate his father as an example, the latter is not the man he thought: he is an underpaid labor trafficker, working by stealing money from the poorest and illegally confiscating equipment for his factory. This realization will finally lead Hatzin to recognize that the masculinity he had taken as a model would soon lead him to ruin.

A violent and criminal masculinity is likewise the subject of Lorenzo Vigas’ excellent La Caja. Hatzin (Hatzin Oscar Navarrete) insists on entering the life of what he believes to be his biological father (Hernán Mendoza), who denies any connection. Not yet fully aware of the kind of work his supposed father does, Hatzin keeps track of his expenses/income and reveals to him that he is paid less than he should be. The parent looks at him in astonishment. He, who lives by deceiving poor people, has himself been deceived without realizing it; and it is the most deceived creature of all ⎯ a little boy looking for his father ⎯ who warns him. Hatzin is all proud, he would even kill to keep his father out of trouble, but soon he must face reality. Although he does everything he can to elevate his father as an example, the latter is not the man he thought: he is an underpaid labor trafficker, working by stealing money from the poorest and illegally confiscating equipment for his factory. This realization will finally lead Hatzin to recognize that the masculinity he had taken as a model would soon lead him to ruin.

A son is also the protagonist of Paolo Sorrentino’s intimate The Hand of God. Fabietto (Filippo Scotti) stares at his naked aunt (Luisa Ranieri) and daydreams of erotically possessing her, or rather being possessed. Throughout the film, Fabietto’s verbs should be conjugated in the passive form: he suffers life, he always looks at it from a non-participatory distance. Only pain brings Fabietto back to the active stage, as a desperate episode of rebellion against a reality that is too complex and articulated to handle. Indeed, having lost both his parents in a tragic accident, he finds himself completely alone. Enrolled in a high school run by priests, he has no friends, no affection or love. He is stuck with his older brother, who no longer has career ambitions and thinks only of his friends and girls. Fabietto, on the other hand, doesn’t even look at his peers, his aunt absorbs every fantasy. But even though the film ends on a hopeful note ⎯ the boy realizes he wants to make movies (the film is an autobiographical confession by the director) ⎯ a feeling of sadness and incommunicability hovers in the air. The boy seems lost in thoughts too liquid to take communicative form. Or perhaps, he is too sensitive and masks his pain in a silence full of suffering. A convulsive attack seizes him at the umpteenth quarrel of his parents (due to his father’s repeated betrayals) and the cries of pain in the finale certify his submerged emotions.

While in Sorrentino’s film Toni Servillo dies prematurely, in Mario Martone’s The King of Laughter, in which he also plays a father ⎯ the eccentric master of Neapolitan theater, Eduardo Scarpetta ⎯ he occupies the entire scene until the end. During a play, the audience, paid to boo, interrupts the parody. Eduardo pretends to have an illness and orders the audience to be told that in a few minutes the company would be back on stage with a new act. His son Vincenzo would take his place. But Vincenzo is stopped just as he is about to take the stage: Eduardo is unable to stay backstage and promptly recovers his position at the center of the scene. A character of a thousand virtues and a thousand vices, he submits to his will all those who work and live with him. He will never recognize many of the children he has had out of wedlock, although he will always keep them very close to him. More than one child tries to rebel, and the extended family is in danger of falling apart several times. But his strength and resourcefulness will prevail: he wins the trial that sees him clash with D’Annunzio and defeats the loneliness of the man alone in the crowd that for a moment strikes him. His children, legitimate or not, will continue in his art. The character is very complex, Martone treats an extra-ordinary virility and the family around him with a sensitive trait capable of capturing both the rigidity and the tenderness diffused in everyday gestures.

While in Sorrentino’s film Toni Servillo dies prematurely, in Mario Martone’s The King of Laughter, in which he also plays a father ⎯ the eccentric master of Neapolitan theater, Eduardo Scarpetta ⎯ he occupies the entire scene until the end. During a play, the audience, paid to boo, interrupts the parody. Eduardo pretends to have an illness and orders the audience to be told that in a few minutes the company would be back on stage with a new act. His son Vincenzo would take his place. But Vincenzo is stopped just as he is about to take the stage: Eduardo is unable to stay backstage and promptly recovers his position at the center of the scene. A character of a thousand virtues and a thousand vices, he submits to his will all those who work and live with him. He will never recognize many of the children he has had out of wedlock, although he will always keep them very close to him. More than one child tries to rebel, and the extended family is in danger of falling apart several times. But his strength and resourcefulness will prevail: he wins the trial that sees him clash with D’Annunzio and defeats the loneliness of the man alone in the crowd that for a moment strikes him. His children, legitimate or not, will continue in his art. The character is very complex, Martone treats an extra-ordinary virility and the family around him with a sensitive trait capable of capturing both the rigidity and the tenderness diffused in everyday gestures.

The piece of the puzzle where the sensitive gaze seems willfully missing is the D’Innocenzo brothers’ America Latina, where an alienating patina of disbelief envelops the entire movie. The directors, minor relatives of a peerless Yorgos Lanthimos, have explicitly declared their intention to narrate the crisis of the contemporary male in a love story that is also a film noir and a thriller. The masculinity expressed by the protagonist Massimo (Elio Germano) is that of an ordinary man, a family man with a suburban villa, a dentist by profession with a hobby of drinking beers with a friend who at first glance is much more desperate than him. This mask of ordinariness hides a monster unable to communicate, detached from reality, with paranoid fits and fear of life outside the norm. Massimo’s madness becomes relevant because of an inexplicable event: the kidnapping and imprisonment in the basement of a young girl victim of violence.

The piece of the puzzle where the sensitive gaze seems willfully missing is the D’Innocenzo brothers’ America Latina, where an alienating patina of disbelief envelops the entire movie. The directors, minor relatives of a peerless Yorgos Lanthimos, have explicitly declared their intention to narrate the crisis of the contemporary male in a love story that is also a film noir and a thriller. The masculinity expressed by the protagonist Massimo (Elio Germano) is that of an ordinary man, a family man with a suburban villa, a dentist by profession with a hobby of drinking beers with a friend who at first glance is much more desperate than him. This mask of ordinariness hides a monster unable to communicate, detached from reality, with paranoid fits and fear of life outside the norm. Massimo’s madness becomes relevant because of an inexplicable event: the kidnapping and imprisonment in the basement of a young girl victim of violence.

If Massimo’s alienation takes on a violent parabola, the total dissociation from reality of Neil (Tim Roth), the protagonist of Michel Franco’s Sundown, borders on a distorted form of ataraxia. Neil is on the beach, alone, drinking the nth beer of his day. It is thanks to the beer that he met Berenice (Iazua Larios), from the local store, who now greets him from the sea. In the meantime, a jet ski approaches and soon reaches the shore. A young Mexican starts shooting a guy near Neil on the beach, killing him instantly. Even the residents of Acapulco, who are much more used to such violence than Neil, flee and run screaming in fear. Neil doesn’t flinch, as if he didn’t even notice. Unfortunately, his excessive imperturbability ends up hurting everyone around him (and even himself!). Neil’s solipsism is brutal; no one but Tim Roth could have played a gait more suited to the character. His silence seems to come from a frightening awareness: a cancer now too widespread to tame. But doubt persists; perhaps this disease has only made clear to him the absurdity of his life. Perhaps he doesn’t even know about the disease. His passive wandering through a violent, thieving Acapulco is the most evident juxtaposition of this festival. His primary impulse seems to be to undo a life as social practice in order to regress to a state of essential, bare, tongue-less living. With Berenice more than communicating he makes love, they cuddle, without many words (unlike Jon and Mira from Scenes from a Marriage!).

If Massimo’s alienation takes on a violent parabola, the total dissociation from reality of Neil (Tim Roth), the protagonist of Michel Franco’s Sundown, borders on a distorted form of ataraxia. Neil is on the beach, alone, drinking the nth beer of his day. It is thanks to the beer that he met Berenice (Iazua Larios), from the local store, who now greets him from the sea. In the meantime, a jet ski approaches and soon reaches the shore. A young Mexican starts shooting a guy near Neil on the beach, killing him instantly. Even the residents of Acapulco, who are much more used to such violence than Neil, flee and run screaming in fear. Neil doesn’t flinch, as if he didn’t even notice. Unfortunately, his excessive imperturbability ends up hurting everyone around him (and even himself!). Neil’s solipsism is brutal; no one but Tim Roth could have played a gait more suited to the character. His silence seems to come from a frightening awareness: a cancer now too widespread to tame. But doubt persists; perhaps this disease has only made clear to him the absurdity of his life. Perhaps he doesn’t even know about the disease. His passive wandering through a violent, thieving Acapulco is the most evident juxtaposition of this festival. His primary impulse seems to be to undo a life as social practice in order to regress to a state of essential, bare, tongue-less living. With Berenice more than communicating he makes love, they cuddle, without many words (unlike Jon and Mira from Scenes from a Marriage!).

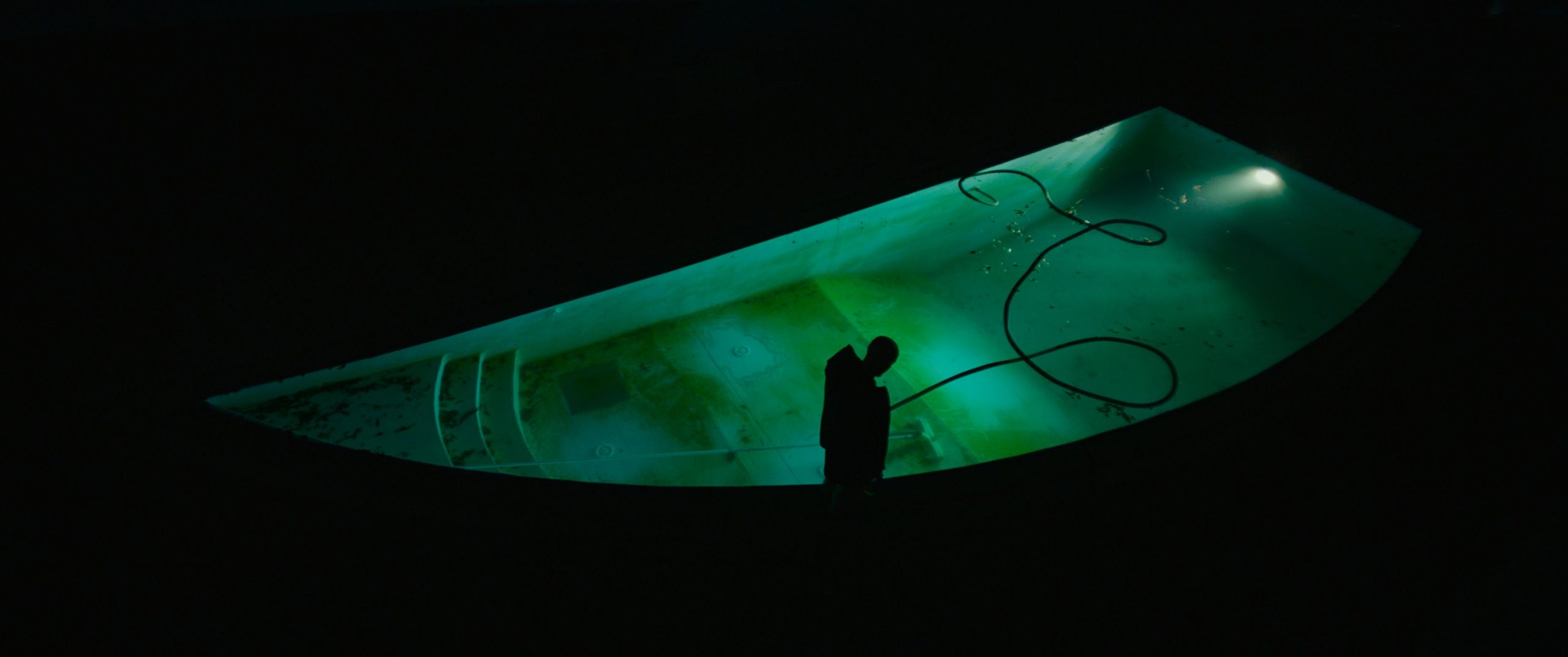

The last piece of the puzzle is shared by two films in competition that are structured around an intergenerational male relationship: The Card Counter by Paul Schrader and The Power of the Dog by Jane Champions.

In Schrader’s film, the male shatters in the violent game of the world. Paying with their lives are William Tell (Oscar Isaac) a former military interrogator ⎯ the lone man in the room ⎯ repentant and escaping his brutal past; young Kirk (Tye Sheridan) seeking revenge to redeem a father who was in turn a torturer; and veteran Major John Gordo (Willem Dafoe) the sadistic officer guilty of every crime. The young man will be overwhelmed by the weight of the male role model he carries on his shoulders.

Finally, antithetical models of masculinity compete in Jane Champions’ The Power of the Dog. We’re in mid-1920s Montana. Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch, really impressive in the part) is a strict rancher who inspires fear and respect in everyone who meets him. He lives wildly by castrating calves with his bare hands, swimming naked in the river, and smearing his body with mud as if it were a purification ritual. He is hypermasculinity in command. The only affection he has left is his brother George (Jesse Plemons), with a much milder temperament and much less overbearing ways. When the latter decides to get married, Phil will try in every way to ruin the life of his brother’s wife and son in tow. Phil is cruel but, as bad and rough as he may be, he hides a tormented, fragile and sensitive soul with a single sincere admiration for his old ranch master: the cowboy Bronco Henry. As the film develops, we understand that the relationship between the two hid something forbidden, erotic for sure, a sort of pederastic relationship like the one between erastes and eromenos in ancient Greece. Bronco Henry is a ghost whose influence will deeply influence the relationship between Phil and Peter, son of Phil’s brother’s wife. Although the boy is ephebic and effeminate, unfit for ranch life and targeted by all the cowboys, Phil, after initial reluctance, takes him under his protective wing and teaches him to live like a “real man.” Soon Phil will have to come to terms with a removed past that leads him into the impossibility of being a homophobic and even homosexual alpha male. Peter, for his part, will show much more resourcefulness and cold blood than expected and will exploit his master’s feelings to condemn him to death, turning the whole game upside down. The lazzo, symbol and talisman of the cowboy, that Phil intends to give to Peter as a final form of investiture, will end up killing the alpha male. The metaphor is powerful: for the hypermasculine Phil, the lazzo is transformed into a rose, a flower to be given as a gift to declare one’s love; for the feminine and cunning Peter, the lazzo becomes a weapon to kill, reversing its function; the cowboy (and what he represents) is now the poison to be eradicated.

Finally, antithetical models of masculinity compete in Jane Champions’ The Power of the Dog. We’re in mid-1920s Montana. Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch, really impressive in the part) is a strict rancher who inspires fear and respect in everyone who meets him. He lives wildly by castrating calves with his bare hands, swimming naked in the river, and smearing his body with mud as if it were a purification ritual. He is hypermasculinity in command. The only affection he has left is his brother George (Jesse Plemons), with a much milder temperament and much less overbearing ways. When the latter decides to get married, Phil will try in every way to ruin the life of his brother’s wife and son in tow. Phil is cruel but, as bad and rough as he may be, he hides a tormented, fragile and sensitive soul with a single sincere admiration for his old ranch master: the cowboy Bronco Henry. As the film develops, we understand that the relationship between the two hid something forbidden, erotic for sure, a sort of pederastic relationship like the one between erastes and eromenos in ancient Greece. Bronco Henry is a ghost whose influence will deeply influence the relationship between Phil and Peter, son of Phil’s brother’s wife. Although the boy is ephebic and effeminate, unfit for ranch life and targeted by all the cowboys, Phil, after initial reluctance, takes him under his protective wing and teaches him to live like a “real man.” Soon Phil will have to come to terms with a removed past that leads him into the impossibility of being a homophobic and even homosexual alpha male. Peter, for his part, will show much more resourcefulness and cold blood than expected and will exploit his master’s feelings to condemn him to death, turning the whole game upside down. The lazzo, symbol and talisman of the cowboy, that Phil intends to give to Peter as a final form of investiture, will end up killing the alpha male. The metaphor is powerful: for the hypermasculine Phil, the lazzo is transformed into a rose, a flower to be given as a gift to declare one’s love; for the feminine and cunning Peter, the lazzo becomes a weapon to kill, reversing its function; the cowboy (and what he represents) is now the poison to be eradicated.

The puzzle is done. Putting the pieces together, it turns out that the resulting image is opaque and the subjects in the background are poorly defined. A spot blurs the surface making it impossible to read.

The puzzle is done. Putting the pieces together, it turns out that the resulting image is opaque and the subjects in the background are poorly defined. A spot blurs the surface making it impossible to read.

George, Phil’s brother in The Power of the Dog, at one point in the film, after he has finally managed to move away from Phil whose attachment exasperates him, is on a hill with his wife Rose (Kirsten Dunst), who is trying to teach him some dance moves. They are newly married, in a moment of simple peace. But George suddenly begins to cry and whispers, “how nice it is not to be alone.” Unfortunately, fate doesn’t smile on the two; Rose, having fallen prey to uncontrolled alcoholism because of Phil, will leave George more alone than ever not long after. The spot on the puzzle now seems to turn into a tear. Is it not the damp, misty curtain that males lift in their melancholy-filled cries? Is not the puzzle itself an ode to relationship? After more than 45 films in 10 days, what remains is a blurry image of male figures too prevalent to become extinct and too lonely to stand out.

by Simone Rossi

CACTUS CLIMAX FW 21/22

Original title: Exercises of Seeing II. The 78th Venice Film Festival and the Lonely Man

Images in order of appearance:

Michel Franco, Sundown, 2021.

Hagai Levi, Scenes from a Marriage, 2021.

Potsy Ponciroli, Old Henry, 2021.

Lorenzo Vigas, La Caja, 2021.

Mario Martone, The King of Laughter, 2021.

D’Innocenzo brothers, America Latina, 2021.

Michel Franco, Sundown, 2021.

Paul Schrader, The Card Counter, 2021.

Jane Champions, The Power of the Dog, 2021.

Jane Champions, The Power of the Dog, 2021.

All images: Courtesy of La Biennale.