Aviva Silverman

The first time I met Aviva was in Florence, at her first solo show in Europe, at Spazio Veda. It was at the end of September and she told me that she would shortly leave for the island of Elba, out of season, in October. I found this familiar at once, I had made the same choice years earlier, and it had not been such an inspired experience (it rained all week long). I hope it has been better.

The first time I met Aviva was in Florence, at her first solo show in Europe, at Spazio Veda. It was at the end of September and she told me that she would shortly leave for the island of Elba, out of season, in October. I found this familiar at once, I had made the same choice years earlier, and it had not been such an inspired experience (it rained all week long). I hope it has been better.

Aviva Silverman: Elba was really beautiful. It didn’t rain, but it wasn’t particularly warm out. My partner Capri and I rented a tin can of a car that slid backwards down some hills (the island is all hills), and we got lost a lot because the roads aren’t well marked. The last day we found this beach full of babies and teens and couples that still had some private alcoves that felt really special.

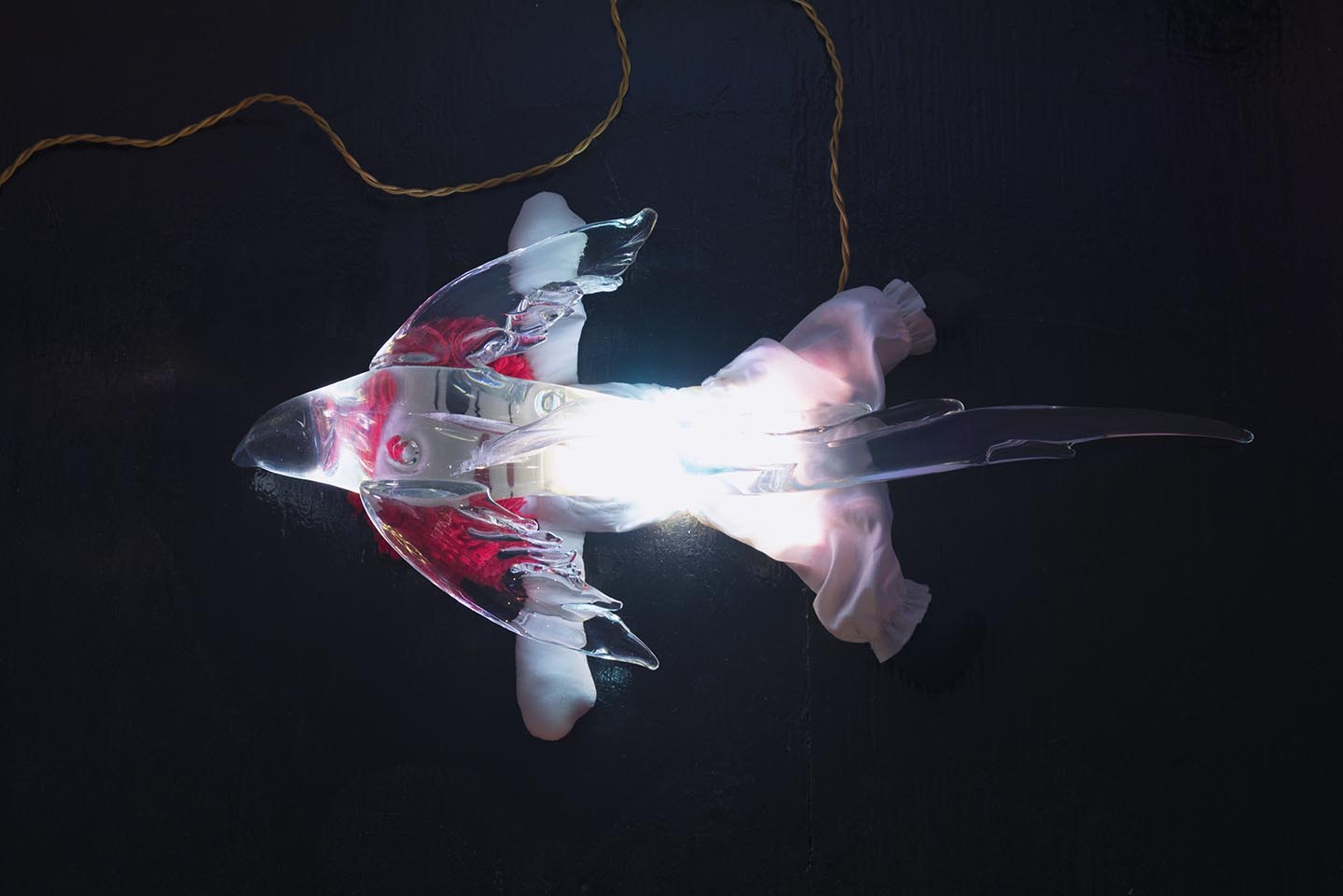

Simone Rossi: On the occasion of that show at Spazio Veda, ‘The living watch over the Living’, you revealed a central focus of your artistic path, namely the figure of surveillors, of recording angels observing life. These divine protectors were part of your following speculation in your second one-person show at Bodega, New York, called ‘Entering Heaven Alive’, which is just over. Will they appear in renewed shapes, influencing space at your upcoming show at Sommer, Tel Aviv, in May?

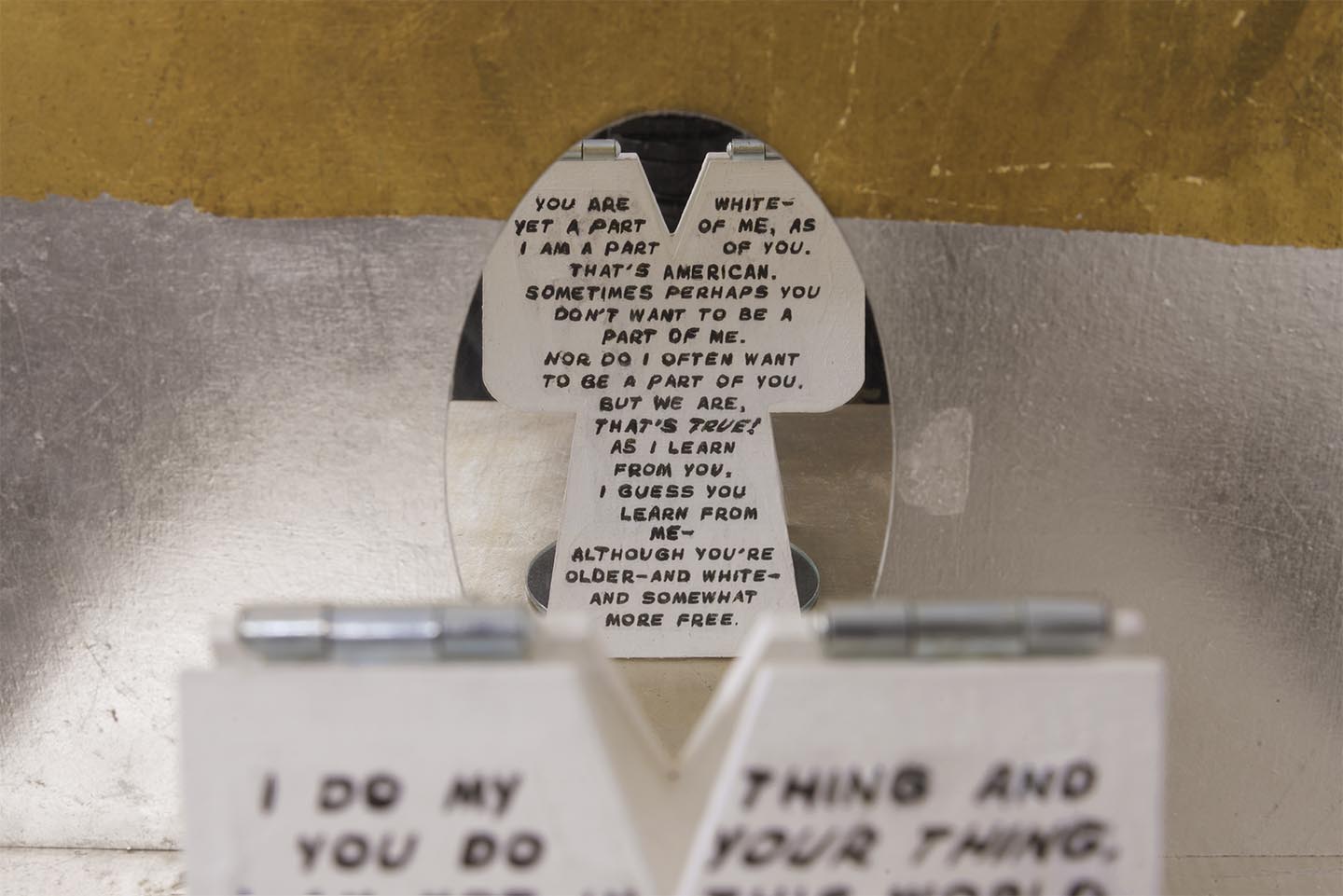

AS: I just went to D.C. and saw James Hampton’s The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly at the Smithsonian museum. It was the most beautiful, thrilling work of art. I’ve been thinking about his piece and the question, “Will there be any new masterpieces in our lifetime?” that my friend Emily asked as we stood before it. Since I’m in this transitory state between shows I’ve been thinking about Hampton’s altars made from tin foil and the other visionary work that lives in the wing of the Museum, and how (I’m assuming) it was willed through the artist’s wound: through hardship, poverty, illness, depression, and this other manifestation that could be called creativity—a burst of vision that finds this container. And then, here it lives “on view permanently” in the U.S. capital.

This makes me think more about religious iconography and the religiosity of art making; how effigies that are mass-made, handmade from tinfoil or otherwise, can bring you closer to the supernal, as well as to yourself and to other histories of survival throughout time. Folk art is a part of my religious art history experience, and I’m trying to make sense (in this question) about my compulsion to make protective symbols, and how that connects to my own personal mythologies and to greater religious iconography.

SR: Your approach to the biblical matter follows a secular tradition that makes the sacred text first of all a cultural text. As you recently observed in conversation with artist Demon Zucconi: “Atheism and spirituality aren’t diametrically opposed”. When and how, according to you, do atheism and spirituality find a bond, do they combine to mean together?

SR: Your approach to the biblical matter follows a secular tradition that makes the sacred text first of all a cultural text. As you recently observed in conversation with artist Demon Zucconi: “Atheism and spirituality aren’t diametrically opposed”. When and how, according to you, do atheism and spirituality find a bond, do they combine to mean together?

AS: I remember reading that Aristotle used to think about angels as intermediary movers within celestial spheres. His text On the Heavens and primary philosophy of the “unmoved mover” speak about angels within the laws of metaphysics, absent religious doctrine. Philosophers including Locke, Descartes, and Spinoza also used angels to explain the phenomena of the cosmos. Angels became a dialectical way of describing non-experiential knowledge. John Dee, Queen Elizabeth I’s scientist who was also a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and occult philosopher, embodied this kind of alchemy where philosophy and mysticism operate as an intellectual mode of speculation. Dee felt that man had the potential for divine power, and he believed this power could be exercised through mathematics.

SR: How much of your practice do you think is influenced by your Jewish education?

AS: All of my education becomes a part of how I creatively think about and approach reality. I wonder if my Jewish education affects my dream-space. Am I Jewish when I dream? I wonder where identity goes then.

SR: The world perceived as a gaze, in which we are subjects-that-see and at the same time objects-that-are-seen, supports of virtual information and material bodies-that-feel, makes us beings who possess a dual ontological status. Has the human being become a sort of secular angel of him/herself, overseer and supervised? data and subject?

SR: The world perceived as a gaze, in which we are subjects-that-see and at the same time objects-that-are-seen, supports of virtual information and material bodies-that-feel, makes us beings who possess a dual ontological status. Has the human being become a sort of secular angel of him/herself, overseer and supervised? data and subject?

AS: I like your question a lot, “all the world’s a gaze”. That’s what my piece “Shrinking World” was getting at in some way: a bronze collar hung neck-height (my height, more precisely) tethered to a hand mirror. All the elements of the piece are composed of the same materials. I’m really interested in how we move around these constructs of control, or lack of control. I keep working it out through mirrors: which way they face, if they are two-way, hand-held, or in the round, and what they can tell us about mediation, identification, and personal agency. I’m reminded of this piece I made in 2008 for my thesis project at MICA called “Free TV,” which is also an extension of this ontological question of control. I feel like these thoughts are sliding into that crazy chamber seen in one of the last scenes of the movie Annihilation, but that’s its own discussion…

SR: I admit that the photographic part, although minimal in your shows, is incredibly fascinating. It manages with great delicacy to make sense of the whole thing with disarming simplicity. In both your latest shows, the two photographs The Custodian and The living watch over the living have had a fatal attraction to me. I am impressed by your selection and reduction ability, which allows you to enclose the entire imaginary in a single shot. At what stage did these images enter the shows’ construction process?

AS: Thank you! I took a picture of Capri, my partner, for the piece The Living Watch Over the Living a long time before the show, but then re-staged it by adding the small image of Sputnik framed on the wall and photoshopping in a different landscape. Those details became more crystallized when I started to hone in on the show more. The image of my grandmother was taken four years ago in a series I made with Emily Shinada. We photographed my grandmother posing with a model in different arrangements in her home, mostly in the chair she sits in, on her bed, or outside on her patio where she smokes. All of those photos still feel really important to me. Choosing just one is really hard, but I like working within those limitations and seeing how they can return differently to you through the passage of time.

SR: In addition to installation exhibitions, you are used to using performance as an expressive medium. How do you understand and choose how to present your work? What method returns you (in terms of self-gratification) the most?

SR: In addition to installation exhibitions, you are used to using performance as an expressive medium. How do you understand and choose how to present your work? What method returns you (in terms of self-gratification) the most?

AS: Self-gratification is really hard to recognize, both inside and outside of making art. During the exhibition of ‘Entering Heaven Alive’ at Bodega I hosted two different meditations: one as a sound bath, and another in breath work. Those two more private exercises felt like the missing link. Showing work feels so consumerist, people come and take (see) on this unrelenting monthly schedule, each month is filled, each month is left, and the work and its context disappear on this experiential felt-level. I am often anxious about the time the show is on view. The pieces ‘survive’ the exhibition, if I’m to follow this semi-hyperbolic mode of thinking, and that’s part of what I think about when making work —what ideas-objects-permutations-of-dreams should have a life? It sounds so authoritarian and weird, but that is a part of the burden of being an author. On the other hand, performance is a place where I feel fulfilled, in that it’s a T.A.Z. (temporary autonomous zone) that lives through a more de-centralizing agent. I love how collaborative it is, how chaotic it is, how it demands presence and how the whole story can be told in 15-30 minutes through a series of monologues or songs, and ultimately how the whole universe is born and dies within that time. Photos never really work, videos never work. Mostly only storytelling carries performances on.