Jannis Kounellis

“I wasn’t born in Rome, I was born in Athens – and made that ancient little journey to get to Rome”

“I wasn’t born in Rome, I was born in Athens – and made that ancient little journey to get to Rome”

Jannis Kounellis

Jannis Kounellis (1936-2017) is a key figure of the Arte Povera movement. The major retrospective of his work is on view now, through November 24, at Fondazione Prada, Venice, in a show curated by historian, curator and director of the above-mentioned Foundation Germano Celant (Italian, b. 1940).

In a collaboration with Archivio Kounellis, from Italian and international institutions, museums and important private collections, more than 60 works from 1969 to 2015 – key to the evolution in his visual research and production – are on view in a dialogue with the eighteenth-century palazzo Ca’ Corner della Regina.

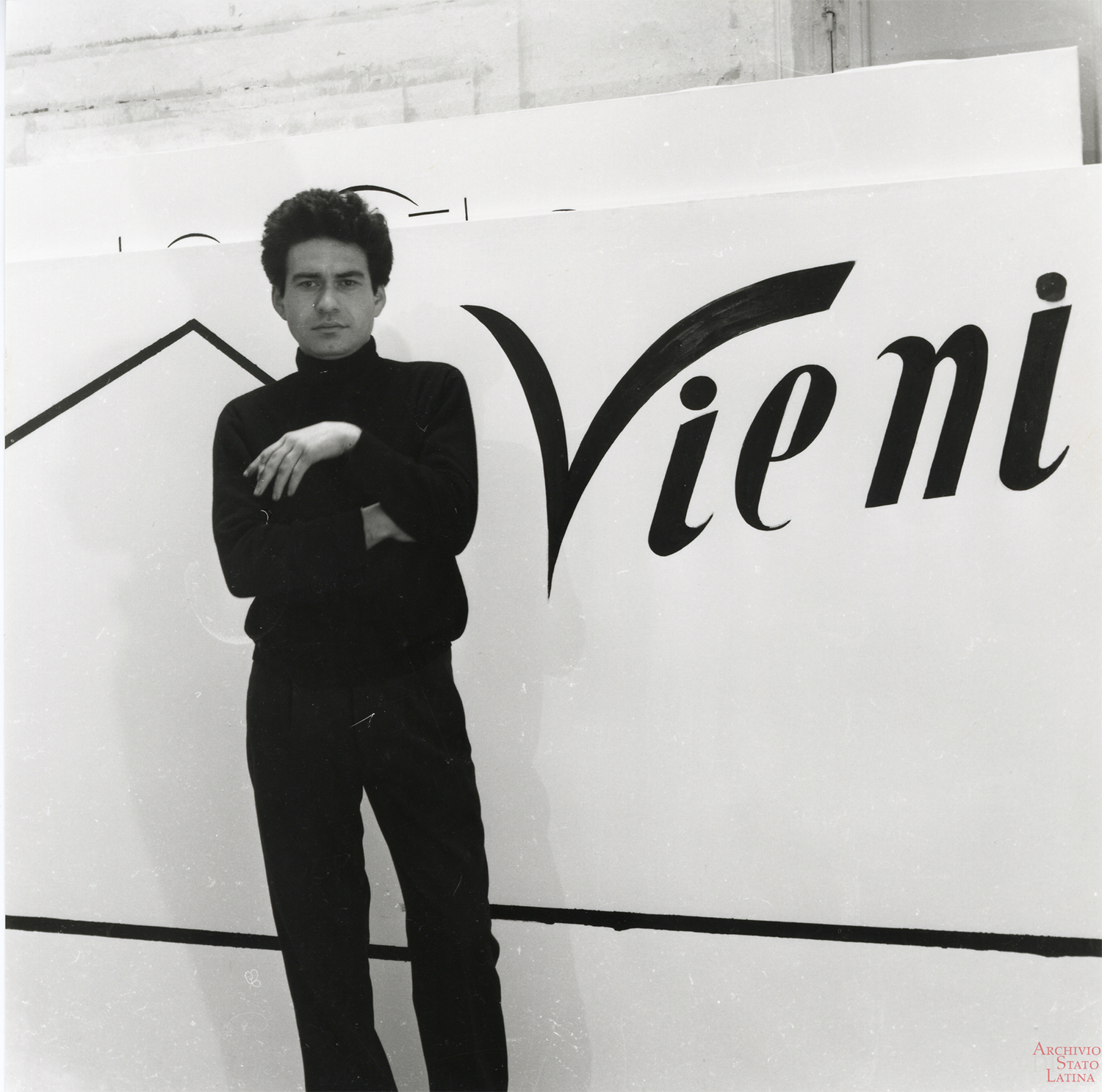

On the first floor, hosting imposing porteghi with stuccos and frescos, can be found works from the early period – between 1960 and 1966 – featuring a historical sequence from his first shows in Rome. In an early phase writings and signs from the street of the city were reproduced, then the artist transferred to canvases and other surfaces fragments of language, in a representation of a deconstructed reality.

“Our generation was the one to build a bridge to a more nomadic approach, though I am not sure if it was by choice, or because we felt forced to become wanderers – wandering monks, theorists or artists – in order to survive,” suggested Celant in a conversation with Kounellis.

“For good or worse, national identity can come down to just that: the frustration that the country brings, the limits imposed by the obligations of tradition. We are modern artists, but I shall not forget Caravaggio’s indication just because I am a modern artist,” he replied.

The desire and the seeking to “hear” the space through phonetic works came into being at that time, influenced by Ungaretti to a certain extent, while the artist was still attending the Academy.

Subjects taken from nature appeared since 1964:

Subjects taken from nature appeared since 1964:

I did a big white picture with a large black rose, not in the center but off to one side. After that, I did another painting with a black structure, like this, and left the other part white. I wrote the word ‘Notte’ on it. Afterwords I did another painting the color of aluminium and wrote ‘Giallo’ on it in red. Then there was a dreaming of a house; it was very rigid in an industrial way, just lightly sketched like this, with a line indicating the horizon, and I wrote ‘Vieni’ on the other part. There are birdcages all around that big picture with the black rose. (Excerpt from: Carla Lonzi Un villaggio pieno di rose. Un’intervista a Kounellis, Catalogo 3, June 10, 1966)

From 1967 concrete and some natural elements became part of his works. He clarified “flowers are not nature’s love, but a shocking thing, like the parrot and fire. But shock is not a mythology of violence. In truth it responds to an Enlightened mentality.” The wool for example, if it is bound, it also helped him unknowingly find greater contact. Symbolically and physically introducing a parrot in a work, the artist subverted the gallery situation: it left the status of marketplace, luxury shop for turning into a theater where Kounellis gave his critical vision of history – acquiring the language, the level and the weight of a literate of the 1800s.

Detaching from a show for him meant lending a dimension to the show itself, opening up a new greater idea of freedom. When the product itself works it becomes obsessive, this condition instead is made for life, liberating, it creates identity and – from the chaos of past – a new order.

The participation in the tragedy of the fundamental artistic event naturally comes from a historic and inevitable memory, the one of the Greek, Italian or European culture.

The written and pictorial language – always about a certain rhythm and how it affected the space – in Kounellis’ practice was transformed into corporal experience as a sensorial transmission and investigation, based on the primacy of vital elements and a terrestrial relationship with art, in contraposition to the elitist, aseptic and authoritative langue of the arts during that time. Sound dimension was explored translating a painting into sheet music to be played and danced, to say something about a certain kind of history and a certain kind of pleasure – in 1971 he had flautists placed in Palazzo Taverna in Rome performing fragments by Mozart – and olfaction was investigated through materials such as coffee and grappa.

The written and pictorial language – always about a certain rhythm and how it affected the space – in Kounellis’ practice was transformed into corporal experience as a sensorial transmission and investigation, based on the primacy of vital elements and a terrestrial relationship with art, in contraposition to the elitist, aseptic and authoritative langue of the arts during that time. Sound dimension was explored translating a painting into sheet music to be played and danced, to say something about a certain kind of history and a certain kind of pleasure – in 1971 he had flautists placed in Palazzo Taverna in Rome performing fragments by Mozart – and olfaction was investigated through materials such as coffee and grappa.

In the installations present in this exhibition the battle is between lightness, instability and temporal nature and fragility of the organic and heaviness, permanence, artificiality and rigidity of the industrial structures, in this case modular surfaces in metal. This opposition is a metaphor of the human condition: the desire for absolute freedom and the physical and moral constriction coming from social structures.

Recalling ancient and mythical culture with a radical approach of visual expression – through components at once natural and historical, corporeal and symbolic – and an energetic exchange with the viewer, fighting the loss of identity from the postwar period, the Arte Povera movement was born.

Recalling ancient and mythical culture with a radical approach of visual expression – through components at once natural and historical, corporeal and symbolic – and an energetic exchange with the viewer, fighting the loss of identity from the postwar period, the Arte Povera movement was born.

Beauty is a revolutionary factor, and beauty as such is an indicator of equilibrium. (…) Moreover, when one has an idea of formal justice, there is always beauty in it. (…) Beauty appears to us as an indication; it is given, and that is why it is lovely. (Excerpt from: conversation with Antonio Lucas, in 11 artists en una cámara frigorifica. Conversaciones sobre la practica sitio especifico, Madrid: Matadero Madrid, 2011, p. 79)

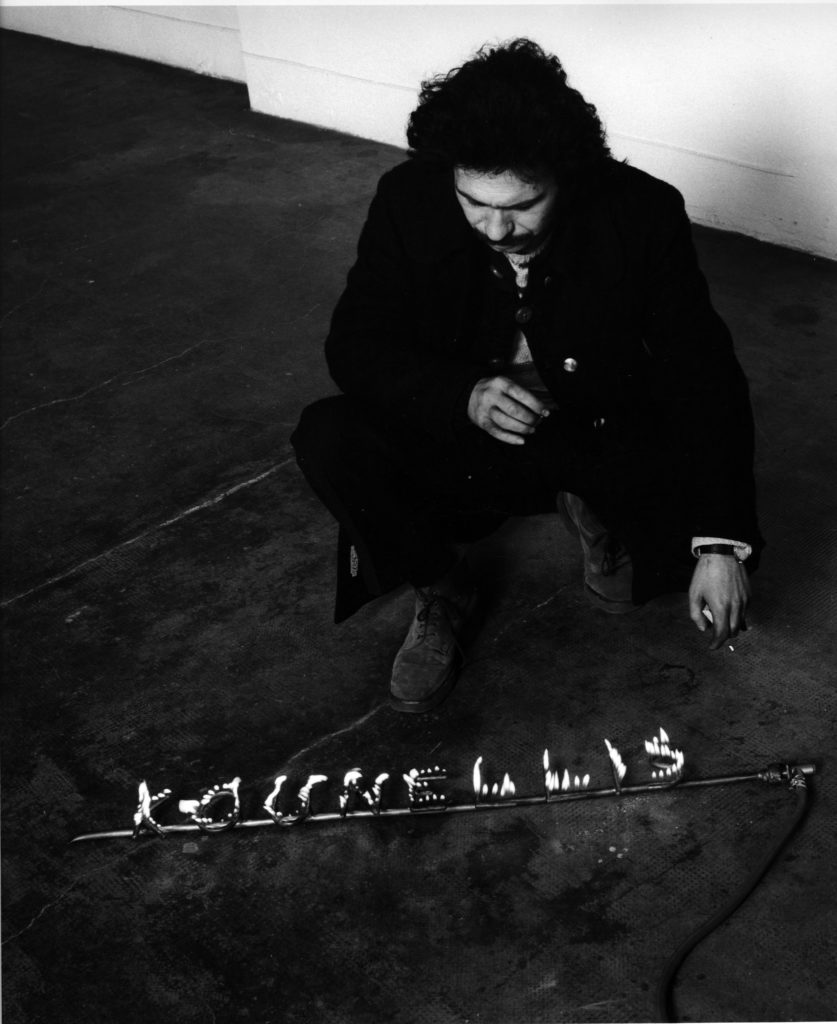

From 1967, the year of the “fire-daisy,” the artist introduced a “fire writing” for the possibility of a revolutionary intervention on reality. As stated by Kounellis himself “fire, in medieval legends, is identified with punishment and purification”. Coming in the form of a gas torch, the visitor is allowed to a potential use – or a greater attention to interior sensations. As a network of flames across the floor, in a work from 1971, it announces the will of a total change. With its iron support, they – alive, real – are above all signs of an image constructed on relationships between structure and sensitivity. Fire is not only heat, but it is also a source of light. It creates shadows, marks volumes, and determined the image. Later in Kounellis’ works, due to a political and artistic more conservative context, it took the hopeless reductive form of a candle, a paraffin lamp, a barely visible cannula along the surface of the painting.

The natural connection with fire, smoke, was seen by the artist as the residual of a creative process, energetic transit, and its passing of time. Left on stones, canvases, walls, fragments of classical sculptures it signed a new painting that differed from the anti-ideological and hedonistic one common in the 1980s. The industrial chimney motif was also developed, its soot and smoke symbolized the end of a possible political and social act through art.

According to alchemical tradition, at the top of mutation and sublime result of combustion there is gold. This material has been employed by Kounellis for instance to underline a condition of complementary crisis, existential and artistic – as in his well known work Untitled (Civil Tragedy) of 1975 made in Naples and exhibited again at Documenta, where the golden leaves covering a wall give the background to himself seen as the black clothing hanging on a coat rack. But with a hope, represented by a lit acetylene lamp. The influence of certain Sienese paintings is evident on a figurative plane, as well as that of another painter the artist loves: Klimt.

According to alchemical tradition, at the top of mutation and sublime result of combustion there is gold. This material has been employed by Kounellis for instance to underline a condition of complementary crisis, existential and artistic – as in his well known work Untitled (Civil Tragedy) of 1975 made in Naples and exhibited again at Documenta, where the golden leaves covering a wall give the background to himself seen as the black clothing hanging on a coat rack. But with a hope, represented by a lit acetylene lamp. The influence of certain Sienese paintings is evident on a figurative plane, as well as that of another painter the artist loves: Klimt.

The lit paraffin lamp and portions of classical statues, plaster casts, return in the artist’s path and support his way of conceiving culture and history – as in a work from 1974 where they appear together laid out on a table. The table – like the bed, the door – is disciplined by human need and Kounellis was interested in working within such measurements. It is an everyday object, a sign of life. In this manner, reliving does not mean reincarnation but reliving the aims. Also the mask helped him representing the Greco-Roman heritage. In the Greek tradition it defines the role and identity of the character, its origins and future.

In his attempt to achieve unknown energy, he employed doors – made of stone, lead, bells, wood, sewing machines and iron reinforcing bars – to close empty spaces and their interiority.

In the central rooms of the two main floors large-scale installations, inhabiting the space, are featured. Shelves or metal constructions contain various objects like coal, ship fragments, coats, chairs, mechanical gears, plaster casts, stones, glasses. For the artist, iron and coal are the materials that best evoke the world of the industrial revolution, the origins of contemporary civilization.

In the central rooms of the two main floors large-scale installations, inhabiting the space, are featured. Shelves or metal constructions contain various objects like coal, ship fragments, coats, chairs, mechanical gears, plaster casts, stones, glasses. For the artist, iron and coal are the materials that best evoke the world of the industrial revolution, the origins of contemporary civilization.

An intervention of different coloured closets and other furniture pieces, conceived for the first time for Palazzo Belmonte Riso in Palermo in 1993, stands on a ceiling challenging the laws of gravity and imitating the impossible perspectives of baroque painting through the casually opened doors. On the ground floor of the palazzo interventions involve the architectural and urban space – like the monumental 1992’s external installation, dealing with the motifs of gravity and equilibrium taking advantage of the formal and imaginative possibilities of the act of hanging, presented in the courtyard and originally conceived for the external façade of a building in Barcelona that it is composed of seven metal plates supporting sacks – tied to the idea of the whole world over maritime commerce – filled with coffee beans; and a walled-up door with stones, of 1972. This kind of door has a distant ancestral mother in the 19th-century novels, it is a matter of an idea tied to something mystical. To complete the retrospective, a selection of documents tracing the artist’s exhibition history – films, exhibition catalogues, invitations, posters, archival photographs – and a focus on his theatre projects are shown.

From Janni Kounellis’ words: “The artist has an intellectual opinion to defend which makes him a participant and a creator of the world. It gives him his drive and the poetic dignity for retrieving the epic. It is no accident that together with shadow and drama, it is that which is unconditionally missing today.” The condition is the idea of being internationalists while preserving the basic reasons enabling an artist to become so. Consciously political, where politics stand for polis, the system one inhabits. For Kounellis “the reality surrounding the artist is a formal protagonist. Caravaggio’s message is one of cultural, political counter-reform – meaning the artist doesn’t necessarily have to follow the trending idea, but can be against it, rediscovering the drama and the past. In this sense, the past becomes more than a shelter; it becomes a condition itself.”

From Janni Kounellis’ words: “The artist has an intellectual opinion to defend which makes him a participant and a creator of the world. It gives him his drive and the poetic dignity for retrieving the epic. It is no accident that together with shadow and drama, it is that which is unconditionally missing today.” The condition is the idea of being internationalists while preserving the basic reasons enabling an artist to become so. Consciously political, where politics stand for polis, the system one inhabits. For Kounellis “the reality surrounding the artist is a formal protagonist. Caravaggio’s message is one of cultural, political counter-reform – meaning the artist doesn’t necessarily have to follow the trending idea, but can be against it, rediscovering the drama and the past. In this sense, the past becomes more than a shelter; it becomes a condition itself.”