Luís Lázaro Matos

In anticipation of his upcoming solo show at Madragoa, Lisbon, in May, I sat down with Luís Lázaro to discuss his next project, find out more about his artistic practice and his intimate alogical relation with the place he lives in.

In anticipation of his upcoming solo show at Madragoa, Lisbon, in May, I sat down with Luís Lázaro to discuss his next project, find out more about his artistic practice and his intimate alogical relation with the place he lives in.

Simone Rossi: In your recent works stand out how central the theme of travel is. A journey in which the animal kingdom accompanies the viewer on an illustrated route. Looking at the next show at Madragoa, I am naturally wondering: where will your next speculation lead us?

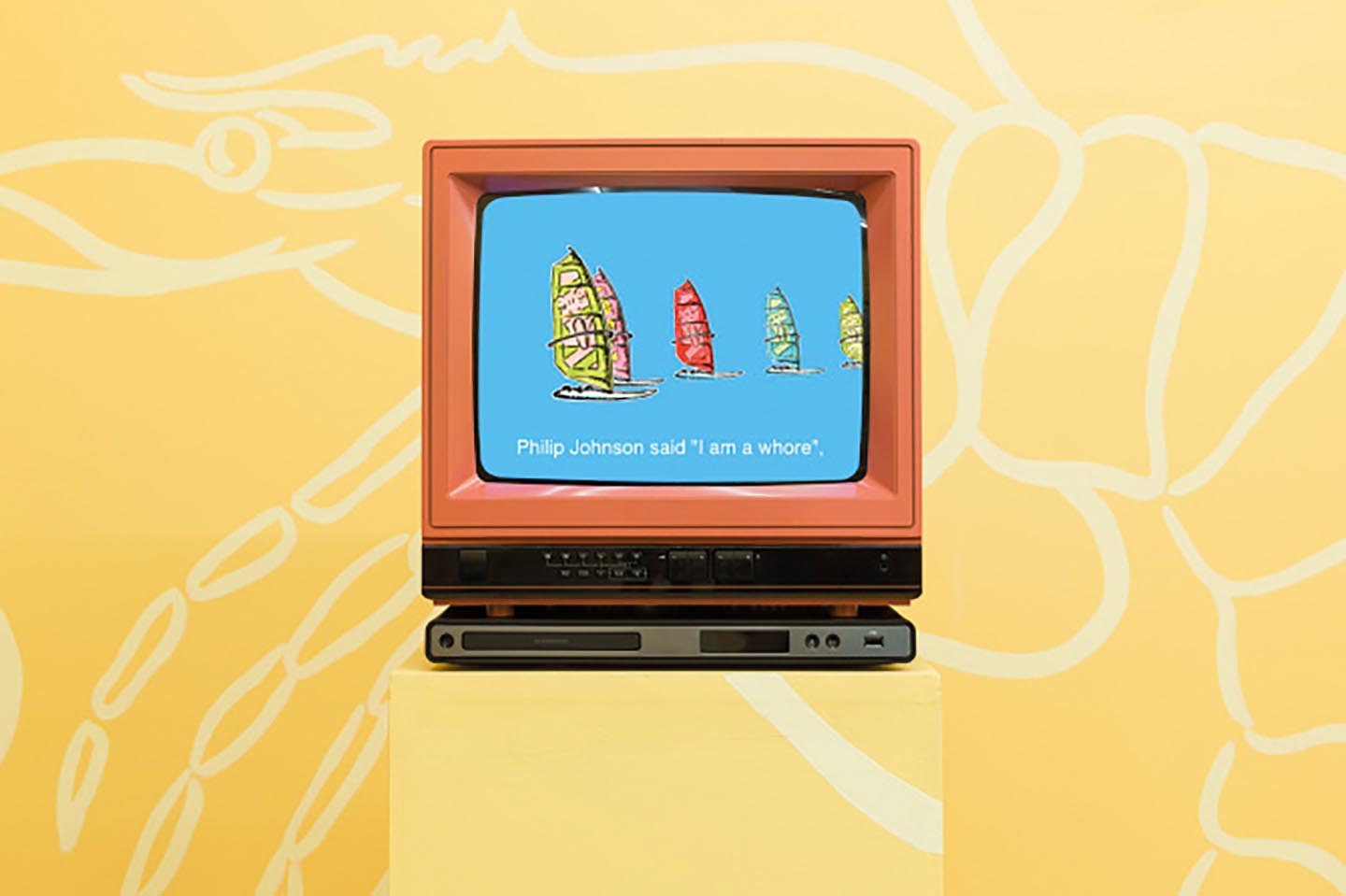

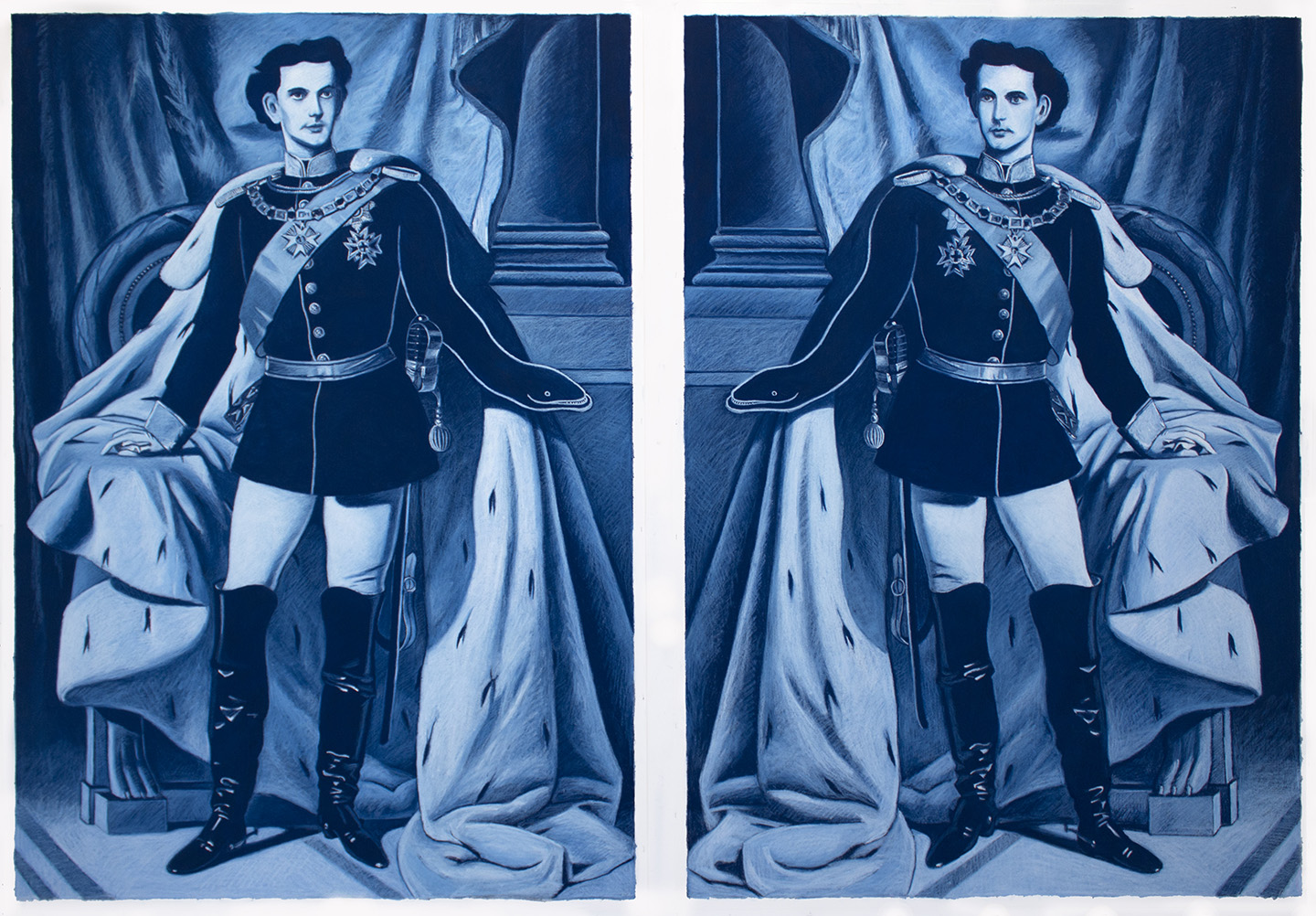

Luís Lázaro Matos: There’s a lot of animal kingdom in my next solo show at Madragoa, it will all be about fishes. The central character of the show will be a tropical eel, that I use to represent the figure of Ludwig II of Bavaria. When I created this project about Ludwig II of Bavaria I thought of him as a sort of eel, living into a beautiful cave inside a coral. It seemed to me that this fish could perfectly embody the misanthropic nature of Ludwig in my narrative. You see, Eels hide in caves, they don’t like to stay around with any other fish. This Bavarian king had many problems precisely because he was literally hiding from his government responsibilities in his luxurious and refined palaces. There’s no theme of travel in this project. I’m approaching the issue of escapism – living in a world of illusions – and what happens when reality bites the fish tail, portraying an eel character with severe egomaniac disturbances. To put it in very general terms – through the link between the history of Ludwig of Bavaria and eel fish – I’m trying to create a narrative in which fantasy clashes with “reality”, as it happened to Ludwig when dethroned.

S: You can move comfortably between illustration, animation, video, painting, drawing: which technique do you consider essential for yourself and which other ones could attract you in the future (if there is any)?

L: I don’t think in terms of which technique is more attractive to me, I see all my works as drawings, even my texts and performances. I’m now making music. I see that as a drawing with sound. I fantasize about one day making a dance piece. All these mediums can reinforce each other. But if I were to talk about drawing techniques, as an example I could mention charcoal. There’s a particularly interesting way this material works. Big charcoal sticks are literally made out of a burned tree. There’s an intrinsic violence in the material that attracts me. I used it recently to make the portrait of ‘Messy Nessy All Over The Place’. The technique was used here only because at the base of the project I felt the need to express myself through a material that was somehow dead. The way the charcoal was done approximately on paper was and is an essential element to be taken into account. What history do materials keep inside them? How can they be performed? And to express what exactly? These are questions I use to organize my ideas. I thought that portraying a monster with charcoal was a perfect wedding. I do this also with colours. Colours often have specific meanings. The whole show at Madragoa, in May, will be in Prussian Blue. The name of the colour is evidently connected with the downfall of Ludwig’s kingdom, which ended up joining Prussia immediately after his death. Prussian Blue is also a very melancholic tonality, it will give the right framework for the show.

S: An architectural approach pervades your practise. How important is it in your artistic method? Are you more interested in it as a modus operandi or as a tool to inquire space?

S: An architectural approach pervades your practise. How important is it in your artistic method? Are you more interested in it as a modus operandi or as a tool to inquire space?

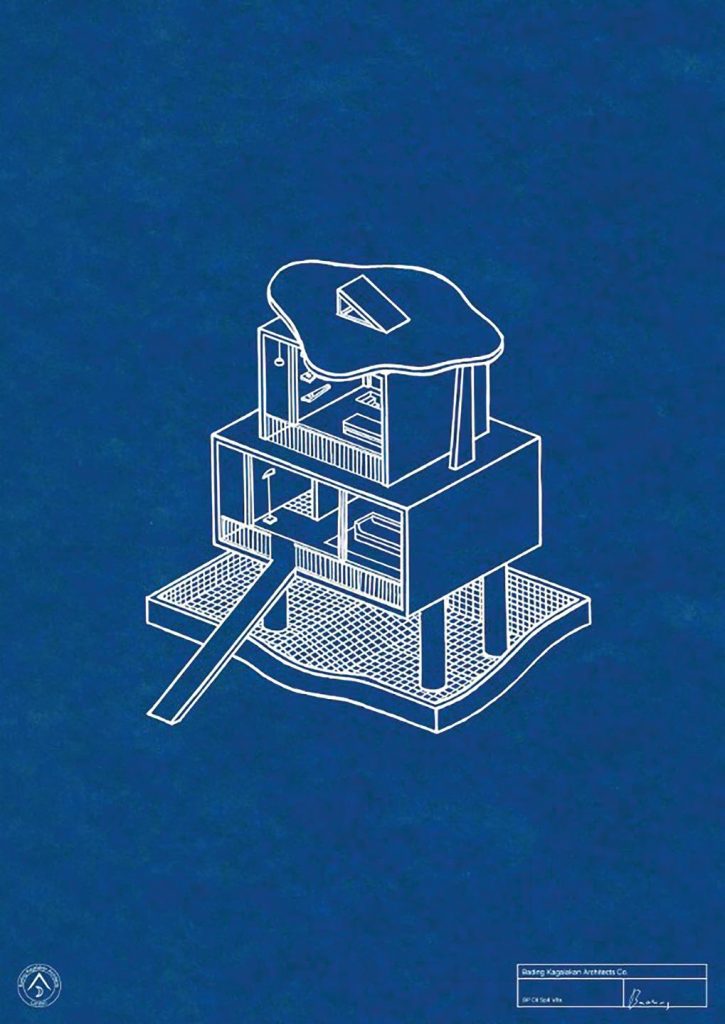

L: I have a very intimate relationship with architecture. This is a very personal matter for me. I have many architects in my family, my father and I grew up in a very iconic neighbourhood designed by Alvaro Siza Vieira – Bairro da Malagueira. I had Japanese tourists knocking at the door to see the house. I remember that when I was a child I wanted to have my own room, so I designed solutions for the extension of the house and gave these designs to my father, so that he could adopt some modifications. Later, when I began to design these architectural fantasies at Goldsmiths College in London, I realized that the lines of my buildings were very much informed by Siza or my father’s works. So, at some point I started to impersonate a role and wrote my architectural manifesto called “Voilá! Manifesto Architecture!” informed by a lot of queer references and Susan Sontag Notes On Camp. In my work Voyage To Papua New Guinea I reacted to Adolf Loos Ornament and Crime text, by metaphorically making my utilitarian Alvaro Siza’s house travel to Papua new Guinea, to finally become an extravagant and hyper decorative version of itself. Maybe I’m becoming a bit Freudian here, but I see this work as a self-portrait: I was the house that was traveling to Papua New Guinea. I was camping myself out of the reality. When I realized that architecture has a lot to do with fiction, I started to see the infinite conceptual possibilities I could make with the design of a building. I could make it travel, change its appearance, become something or someone else, give it a character, even “emotions”.

S: The several wall paintings in your installations immerse the viewer in an atmosphere of sweet hypnosis, and are almost able to enrapture him/her, making him/her more indulgent; how do you explain the choice to always use only two background colours?

S: The several wall paintings in your installations immerse the viewer in an atmosphere of sweet hypnosis, and are almost able to enrapture him/her, making him/her more indulgent; how do you explain the choice to always use only two background colours?

L: Very simple answer: when I install, and most of my murals were installed in art fairs, I often only have ½ or 2 days to paint them. If the colour scheme becomes too complex, the risk of not working is very high, and it’s difficult to repaint the 16 m walls in half a day. In addition, I’m very afraid to use many colours in the murals. I know that one day I will overcome this fear. But I don’t want to get over it during an installation at a fair. It seems too stressful to me. But I would love to make something very Kandinsky like one day. The Madragoa mural in May, as I said before, will be in different shades of Prussian Blue, it makes no sense to add another colour. At Kunsthalle Lissabon it had to be turquoise, in order to give a sort of Hockney-swimming-pool vibe.

S: If I think of Messy Nessie All Over The Place (when you play alone, you always lose) or The Nomadic City of Camela, among others, I let myself get carried away towards a fairy-tale and dreamy world, made of quiet and fluctuating creatures, in complete harmony with the environment that surrounds them, so much that they seem to be made of the same substance. Everything is so relaxing but at the same time weird, so far from the real. What does this approach represent for you?

L: I feel that the character in ‘Messy Nessy All Over The Place’ is a bit uncomfortable. It’s a Lochness monster, plays tennis alone and smokes at the same time. The player doesn’t seem to have a very healthy life, my challenge in every project is how to make the reality I create credible. I believe that it is necessary to approach my projects by suspending the judgment of credibility. Often, it’s because I’m never really sure if what I’m trying to express it’s true or even relevant, so I kindly ask the audience to believe it, by knitting concepts, elements and shapes carefully together. In the end, I offer them at least an aesthetic experience. I really want people to believe Ludwig of Bavaria was a self-obsessed, misanthropic, egomaniac and self-delusional tropical eel. I really want people to believe that in the depths of the ocean there might be some beautiful corals inhabited by a bunch of Clown fishes that shout things like: “Mach Bayern Wieder Großartig” (Make Bavaria Great Again).

S: In ‘Smile You Are In Spain Studio’ the re-semantization of Munch’s scream allows us to contextualize it in a landscape of architectural holidaying of a cliché Spain. Extracting elements from their kingdom and reactivating their ability to signify is an indispensable tool today. Images constantly require it. How do you consider your role as an artist in a European Lisbon context today? And how would you re-contextualize it?

S: In ‘Smile You Are In Spain Studio’ the re-semantization of Munch’s scream allows us to contextualize it in a landscape of architectural holidaying of a cliché Spain. Extracting elements from their kingdom and reactivating their ability to signify is an indispensable tool today. Images constantly require it. How do you consider your role as an artist in a European Lisbon context today? And how would you re-contextualize it?

L: I have an idea for a project about Lisbon, but I can’t reveal it yet. One day I wrote a story about a cafe next to my mother’s house by the beach, in Cascais. The cafe was called Mar à Vista (Ocean view). For almost 20 years the only thing you could see from it was a very ugly condominium, whose construction was interrupted because one of the investors ran away to Brazil with money. So, the only thing that most of elderly people spending their afternoons there could see was actually a bad view of the building, not the sea. I could do something about that.

S: How much of your artistic practice is influenced by the place you live in? Lisbon, for gexample, is a city that has been undergoing many changes in recent years, what impact is it having on its inhabitants?

L: There’s a lot of nonsensical elements in my work. Do you know any other more fascinating and senseless reality like Lisbon from which I could draw inspiration? I want to know, I could move there…. A lot of people are experiencing very different things, I can’t complain a lot. There are more galleries, more concerts, more people from abroad, it’s becoming increasingly cosmopolitan. At institutional level I’m concerned that there is not enough money for cultural things. If Lisbon becomes a party playground for spring breakers I would not be happy. I’m worried that the rental market will force me or my friends to leave the city centre, which is still the most vibrant place to develop our projects. I would hate if Lisbon became something as hideous as Barcelona – A theme park for tourists. Maybe it won’t happen, we don’t have buildings in the shape of a lizard. I still think custard tarts are more boring than Gaudi. I understand why people go to Barcelona.