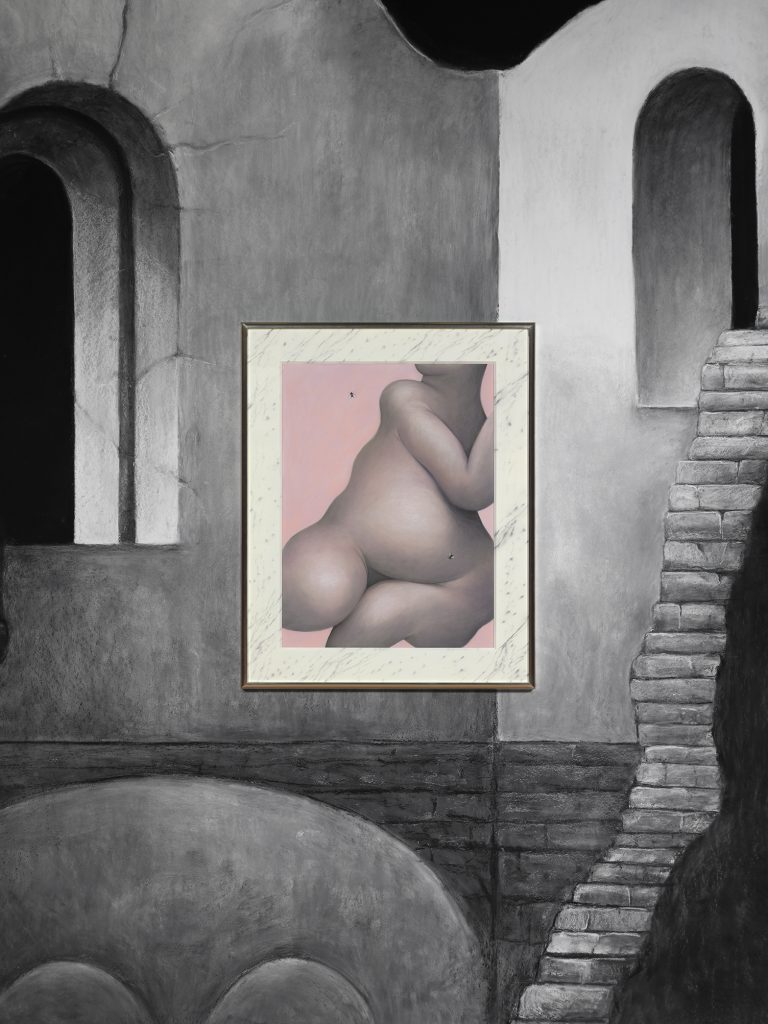

Nicolas Party. Before and After That Time

On a pleasant summer morning, I set down with Nicolas Party for a conversation on the occasion of his solo show Rovine [Ruins] at MASI in Lugano on view through January 9, 2022, unveiling the behind the scenes of the exhibition, his practice and success, thoughts on nature in contemporary times, and a glimpse into his personal life.

On a pleasant summer morning, I set down with Nicolas Party for a conversation on the occasion of his solo show Rovine [Ruins] at MASI in Lugano on view through January 9, 2022, unveiling the behind the scenes of the exhibition, his practice and success, thoughts on nature in contemporary times, and a glimpse into his personal life.

Martina Alemani: The show at Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana [MASI] is the first major monographic exhibition of your work ever to be displayed in a museum in Europe. How did you build your style of extremely vibrant color palettes and simplified figuration, elaborating a universal and timeless language?

Nicolas Party: We never really know where our perceives come from, because it is a mix of what our parents have been showing us during childhood, the cultural environment, and personal taste. In terms of the bright and strong colors style that I have, I connect it to when I was a teenager, I was doing a lot of street art and graffiti at that time, and to make graffiti that are visible in the street or on trains you need to use very bright contrasts, very graphic styles, you do not have much time to see them so you want your art to be visible and direct. Since I did that from age 12 to 19, I feel that it definitely drove what my taste and color palette are in my work today. There is another interesting little anecdote, a French historian specialized in Middle Ages area – called Michel Pastoureau – studied the language of that time, which was also full of logos. It happens that in Switzerland, because of its federation of cantons, they still have those logos and when I grew up, I saw them everywhere. When Pastoureau was asked about this style, he pointed out that when you grow up in an environment that is still actually full of the presence of images and graphics from the Middle Ages, you then tend to create art that is graphic. It is true that there is a tradition of graphic and colorful arts in Switzerland, especially after World War II. There is something that visually is kind of structured, like for example with Max Bill or Le Corbusier, both in those different references. This is also my background, being born in Lausanne.

MA: How do you frame man’s relationship with nature in contemporary times, between exploitation and destruction on the one hand and the anguished desire to preserve and protect it on the other?

MA: How do you frame man’s relationship with nature in contemporary times, between exploitation and destruction on the one hand and the anguished desire to preserve and protect it on the other?

NP: In my still life and landscape works, especially landscapes, I present a nature that stays without human transformations or human presence. The history of landscapes speaks of a conquest by humans, either in the Romantic era the human presence is overwhelmed by the mountains or nature – if we think about Caspar David Friedrich or Arnold Böcklin. Or in the United States, with the Hudson River School, where basically the landscapes are very majestic, but they are all representing how humans and human culture were conquering the wildness, especially in the western US. My landscapes do not have human presence and I think the feelings around that are that for a long period of time in Europe humans were crossing the Alps, etc. with the idea of conquering and having power over the nature, but nature is more powerful than that and at some point it switched to the extent of where we are now: in a stage of a complex regret of conquering and destroying everything. We are in a very interesting moment where we want to recreate nature with some sort of romantic idea of what nature is: replanting trees, re-putting wild animals right back where they belong… but there is still complete control and debate on what nature should be. Should we bring back wolves to forests? How many, which kind? We can almost choose which nature we want to have. It is also scary, because we know that those changes – that we have longed for much time – will be completely devastating for our environments. We have seen that nature can live without us, but we can’t live without it and we need to find a way to live together. We have been in a very strong conflict with each other, humans, and the idea of nature. But we live on the same planet, we are nature too, we are also animals. So, what I want to represent is a kind of idealized nature that we want to create, that is properly composed and where the colors are beautiful. It is almost a pure fantasy, you can see it even in the absurd colors that I use, that turn nature into a nightmare as well.

MA: It is kind of weird and true, we want the nature back but we still want to control it.

MA: It is kind of weird and true, we want the nature back but we still want to control it.

NP: Exactly, and even now we are asking South America, like to Brazil, to stop cutting trees, but we have already done it here in the west. We did cut down a lot of trees. It is strange to tell this to the other side of the world, they want to plant vegetables too, they say “you guys have done it, why can’t we?”. We moved entire big forests.

MA: This ambitious exhibition is a project you conceived on the basis of the specific structure of MASI’s largest exhibition hall. Here, on an imposing scale, its soaring, centrally planned architecture is divided into five distinct environments, each dedicated to still life, portrait, rocky views, caves, and landscape. Why do you work on a recurring motif?

MA: This ambitious exhibition is a project you conceived on the basis of the specific structure of MASI’s largest exhibition hall. Here, on an imposing scale, its soaring, centrally planned architecture is divided into five distinct environments, each dedicated to still life, portrait, rocky views, caves, and landscape. Why do you work on a recurring motif?

NP: After my Master’s in Glasgow, I started to divide my production: landscapes, still life, portraits. Now I take one of the genres and don’t mix them. A portrait is just a portrait, there is no landscape on the background. And if I do a landscape, I don’t put humans in it. Also, if I do rocks, there are no trees. The idea is trying to investigate and get to the essence of the motif and especially how it is metaphysical, symbolical, meaning. If you just make one motif and repeat it, you start to investigate what the motive is, as an image or vehicle for storytelling. The show is built around these five topics, the central red room is where the portrait is and on each side of that room there are different elements of nature: landscapes, rocks, caves, and at the end there are the fruits, taken out of the trees and put on top of each other. But the fruits are not on plates, the idea is that all that is depicted is just fruits. So, the human presence is in the middle, and on the other sides there are the other motifs. Starting from the position of the motif and myself, I research the different uses in history and in various cultures. The cave is an interesting motif, it represents the beginning of civilization, but it is also a metaphor of birth. A cave is also where death occurs in the history of the Christianity, and where there were the first traces of art: in our imagination the cave is the place where art was born, the origin of culture. There is a clear fascination for that dark, secret place. The cave was also used for Plato’s metaphor of shadows, and the fear of the outside. So being in the cave and looking at what is on the walls, making the outer wall feel like an illusion. It is a commentary on what images and art are in our perception of the natural environment. By doing and calling out in a very simple way, going straight to what it is and not finding another way around it, you can reach those themes: it is a cave and, what is cave and why, is interesting. You don’t necessarily have to see them when you see the cave, they also stay differently in one’s memory.

MA: Why it is such important for you the concept of ruins? I find it relating to the concept of attraction.

MA: Why it is such important for you the concept of ruins? I find it relating to the concept of attraction.

NP: Ruin is a new motif that I have been using in the show, it came out in the period of time when I had an idea for the exhibition. It was related to the fact that the world was clearly changing, there was a perception of decay and destruction happening all around us and also of displacement: a before and after that time. Ruins have been used as a symbol of that moment, where a past is gone, and in Romantic era it turned out that nature came out of those ruins: a metaphor for rebirth and restart. Ruins will never be a symbol of complete destruction, of course during the World War I in all the painting there was an idea of apocalypse and there was nothing growing, it was negative. But in the Romantic era it was often a symbol of transition, of how we cut the past and how we – by romanticizing the past – can still see the glorious side. There is an active look on reimaging the past and rebuilding a (hi)story in our mind.

Ruins represent layers of history building on top of each other. Here in Lugano, close to the Museum, there used to be a hotel and next to it there is the church of Santa Maria degli Angioli with Bernardo Luini’s fresco from the XV century. The church was a monastery that was destroyed and also the hotel was built over the traces of that. The hotel became a ruin at some point, as it was closed. And next to the hotel there was a ruin before the Museum. There are different layers of time and functionality in architecture, and in how it remains. I find it pretty fascinating how you see it as a whole, but they have all completely different functions. The attraction is probably given by how you put the story of the past in there, the feeling of the fear of destruction but also the feeling that something is being rebuilt – so there is also energy.

MA: How was born the collaboration with MASI and the two curators of the show, Tobia Bezzola and Francesca Bernasconi?

MA: How was born the collaboration with MASI and the two curators of the show, Tobia Bezzola and Francesca Bernasconi?

NP: I met Tobia in 2013, when he was the director at the Museum Folkwang in Essen. He invited me to be part of the group show Just What Is Not Is Possible. Painting in space. When he started as director at MASI, he called me and invited me to see the space. He soon asked me if I wanted to do a project. Of course, I was very happy about that and then we decided to use the space downstairs. After that, I started to work with Francesca in terms of exploring different motifs and which room will be what, with practical and artistic discussions. She also wrote the texts for the catalogue on each theme. It was a very dynamic way of working.

MA: Your artworks have been critically and publicly acclaimed and have been displayed in renowned institutions. What do you think has been the key to your success?

NP: That’s difficult to know, you always hope for some sort of response when you create anything. I don’t think you create, write a song or a book, without the terms to be shared. Sometimes when you cook something, you are much more excited about other people eating it than yourself eating it. There is an idea of sharing, a feeling of wanting to express something. You have had that since you were young, when you have brought in a drawing you have done to share it. Even when you are creating art, you like it and of course want to share it and have a reaction, make people feel something – like “thanks God someone did it!”. People enjoy it, share it, your art is growing. You have not a clear idea of when and how things start to get bigger. It is important to be just very honest with yourself, with what you do and why you are doing it and not pretend you are more skilled than how you are. It took to me around 10 years to realize that people just asked me to do exactly what I wanted. That’s hard too, sometimes you don’t know what you actually want. You are constantly asking yourself: is it exactly who I am, what I wanted? It is a complex kind of approach of the self, the influences, how the outside wants to interact with you and vice versa. It is interesting.

MA: Which is the most significant encounter you had during your career?

MA: Which is the most significant encounter you had during your career?

NP: It has happened at different stages of my life. I had a teacher when I was about 10 years old who told me that I could not only play with my art, but also build something. You need some people to open your mind, and doors. Another person is Toby Webster, when he invited me to do a show at his gallery in Glasgow. The Modern Institute has a very international audience and that really changed my life professionally and therefore artistically. Six months later my life was so different, by exhibiting there I met many people that gave me different inputs. The exhibition at MASI is also important, it is a big show, there is press talking about it and it reaches a lot of people, I get many things back from this.

MA: What are your plans for the future?

NP: Because of the pandemic there have been a lot of postponed shows, so this year there is a little bit of queuing from the last year and a half, all packed up! I am having an exhibition in Germany in Hannover (Kestner Gesellschaft, Nicolas Party | Stage Fright, curated by Lea Altner), in Beirut, and in New York. Again, there is a lot going on this year. I will start installing a show in Montreux also, opening in February 2022. Lots of things are coming up for sure!

MA: You are now living in New York. What are your favorite spots there?

NP: In New York the museums are my favorite thing to do, and I love old paintings and different historical periods, so the Met for me is always a great place to go. I like this kind of thing, I was in Milan, and I went to see The Last Supper. It was not open to the public; they were taking close-up photos. Standing in front of it was extremely magical.

The Frick Collection – now they moved it to another building – is also a place to go in New York, to see the prominent collection. In terms of exhibitions, I think the Morgan Library always hosts fantastic little exhibitions that focus on works on paper – it is also famous for its collection – or that are book–related.

In terms of venues, my girlfriend is from Los Angeles but she studied in New York and her family is from the city so she knows it very well. I like the Bemelmans Bar – inside the Carlyle, a Rosewood Hotel – with masterpiece murals by Ludwig Bemelmans, the creator of the classic Madeline children’s books. The cocktails are fantastic. I love this kind of old fashioned, art deco bar. And Milan is a haven for this!