Oliver Osborne

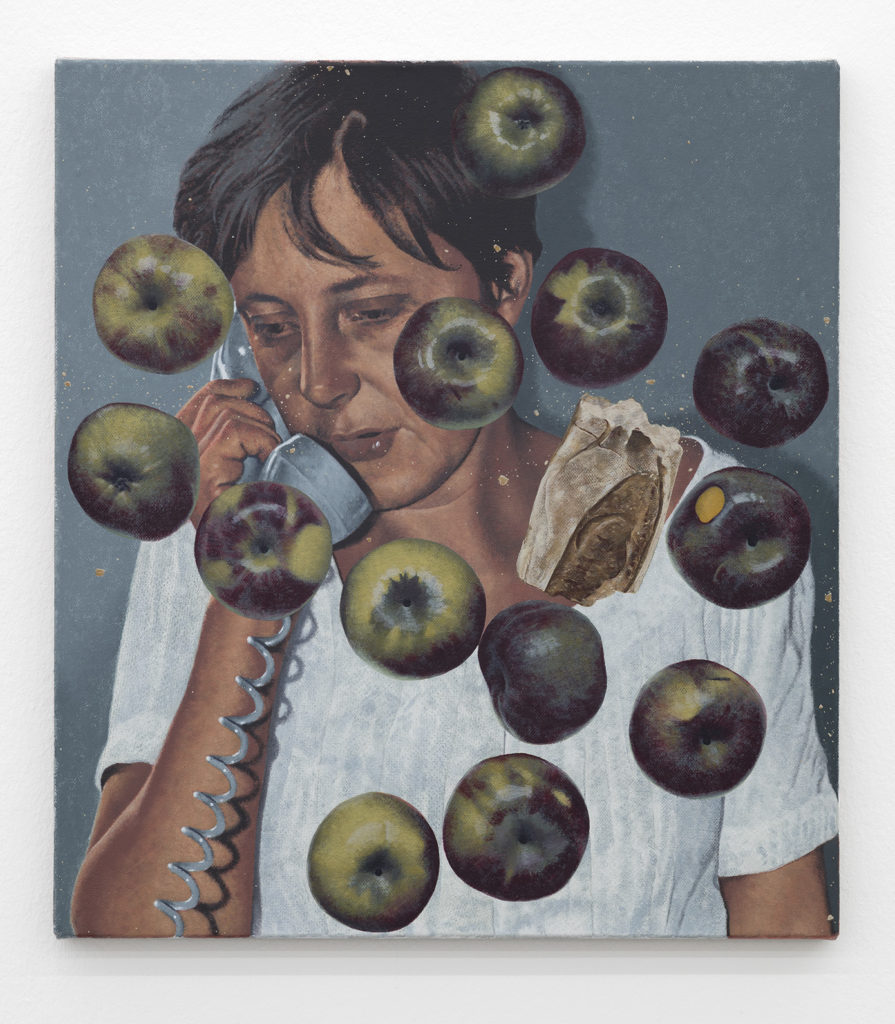

A young GDR era Merkel – as stated in the exhibition’s text by Eoin Donnelly – is depicted in and provides the title for the latest show ‘Birth, Education, Leisure, Death’ by Oliver Osborne at Gió Marconi in Milan.

Standing on one of the gallery’s walls together with other paintings, a moment of questioning and contemplation is provoked. Apples and bread fall on her static and obsolete image, as the phone she holds, showing the power of painting in how images lose their specific nature over time through a drawing out of the non-specifics and of the vagueness of its subjects.

After taking a proper look at the numerous and different plants and apples still-life paintings – common signifiers in this Language – you understand that a realistic representation of objects is never prosaic.

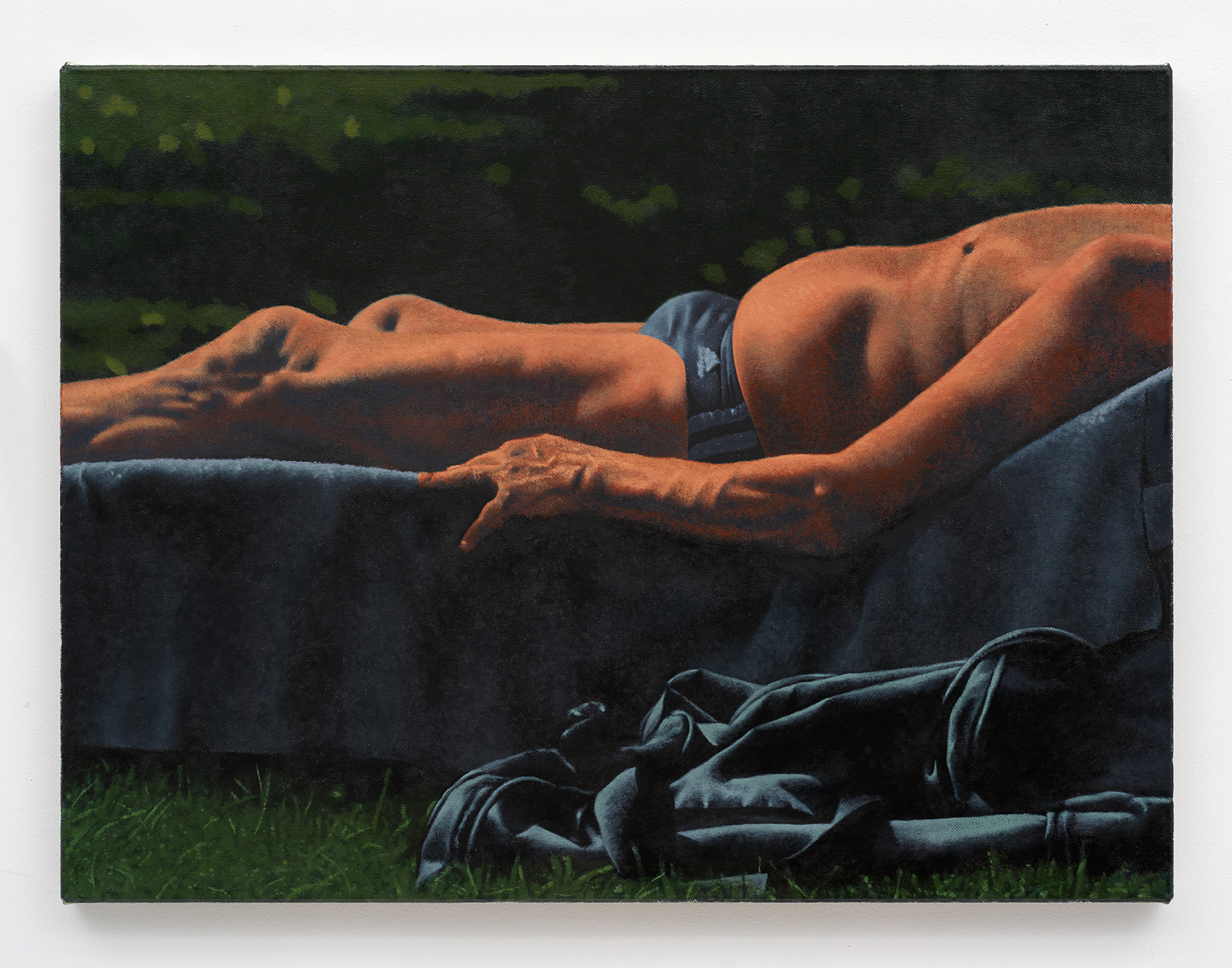

Maintaining this language, you can play with what you see as a corpse on the linens. A Reclining Nude is, in this case, a modern man (an aged fashion entrepreneur sunbathing in his garden?) that was just a Reclining White Man when being represented wearing an Adidas swimsuit.

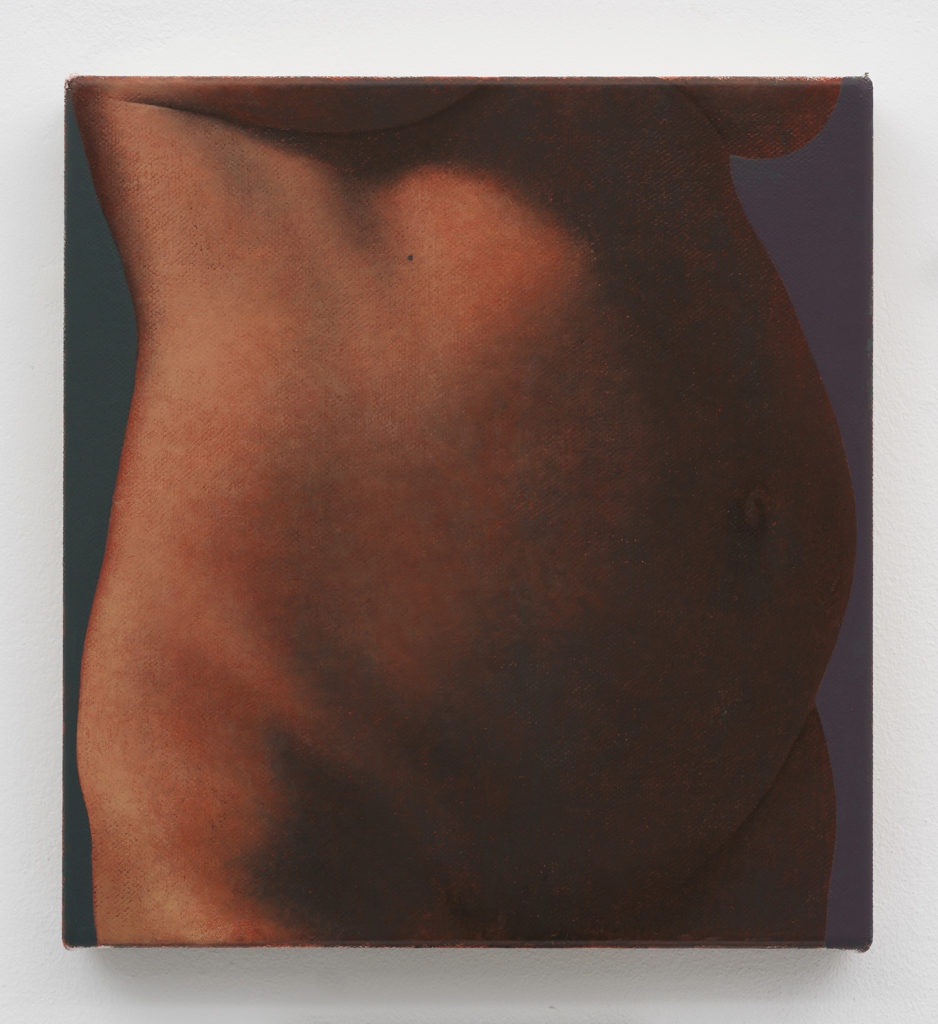

Does a pregnant woman’s belly really need overlaps?

By describing his figurations as some kind of abstract, Oliver Osborne attempts to arrest interpretation and to return it back to itself.

In this sense, a Henry James quote reported by Donnelly is very interesting: he described how relations “really stop nowhere” but it still is the job of the artist that makes them “happily appear to do so”.

A process painting is recognized also through THE FCK SEX ISM LORRY work when entering the gallery. A large pigment print on canvas displays a beautifully green urban truck and then its back, with the vertically sprayed words ‘FCK SEX ISM’ on the image of an apparently common woman on her knees, begging an apparently common man.

As for the pregnant belly, the meaning is immediate as the artwork is close to every day language.

Like a personal veiled prayer through oil colors, the apples and plants’ leaves come in succession with an effort of relieving oneself from whatever else in the world knocks on our awareness.

There is also the sacred representation of bread.

Being physically introduced to the exhibition by the statement on the lorry, the masculine abuse of power reminds you that we still live in this post-feminism era; a concept which is reinforced in the Merkel painting.

In this worldwide political situation, it is not at all surprising that a certain kind of white man feels almighty and his female counterpart finds herself on her knees for him.

When it comes to branding – do we lose purity when we are covered by visible signatures? Nevertheless, this attitude of branding nowadays seems a necessity in order to feel relevant.

Thoughts go to a beautiful scene in the recent Italian movie La paranza dei bambini [The children’s trawler] inspired by a novel by Roberto Saviano in which a bunch of sixteen-years-olds can finally spend the money they earned in a street wear shop in Naples, selling the coolest brands.

In contrast, a naked body immediately speaks of something primal.

When you see a naked pregnant belly, considering the context, it remarks a courageous choice: if it is a boy or girl – the hidden future to be discovered.

In the artist’s first exhibition at the gallery in 2015, The Neck, elements of figuration were mixed between appropriation and abstraction.

The neck is a good metaphor for the connection between thoughts and feelings, something material and ideal, in all its fragility and importance.

Among the sensitive subjects depicted in different ways, there were a rubber plant, a small orange pot, a pregnancy, a caveman, a dog… a text painting – where abstraction is discernible – full of meanings (Getränke, beverages – from store’s signs) which appear figurative by the fact of it being a text.

Osborne’s clean oils, acrylics and silkscreens hit directly and silently a subject matter of language, comprehension and translation.

In the book Oliver Osborne: European Paintings, by Mousse Publishing, with texts by Terry R. Myers and Nicholas Hatful, it is sentenced: “The categories in which his paintings could be situated remain well-placed themselves not because they have been kept in their place as dogma but rather because many artists have worked hard to resist those aspects of choice that have too often and too easily become limiting, if not exclusionary and reactionary”.

Umberto Eco expressed the concept in the words: “How can we not fall on our knees in front of the altar of certainty?”.

Laura Owens, as demonstrated in an interview, has been very much on point about what the death of painting wasn’t able to extinguish: ‘painting does things, and why wouldn’t you use all the things it does?’. “This is the attitude adjustment that emerging painters such as Oliver Osborne have taken on and then intensified to up their game. Well versed in crucial aspects of image culture (its production and analysis), and with an anything-but-lacking desire for the material conditions of making and, yes, the dexterity of both hand and brain, Osborne has through his work already established that the long-standing ways and means of painting (long, long before modernism) are not all that played out after all.

Going a little back in time, Isobel Arbison wrote on Frieze about a summer show of the artist together with two other young Londoners in 2012 at The Approach: “John Constable once called his clouds ‘the chief organ of sentiment’ and so it seems that Osborne’s combinations are a ploy: pitch one didactic pictorial device against another and see what rebounds. As cloud effect or rubbery leaf are combined with fairly humourless educational illustrations, they demand fresh attention. What do we see when we’re not looking (…) – a question that gives these paintings critical purchase”.