Mark Flood. Pathways

On the occasion of Mark Flood’s solo exhibition “Battlefields” at Peres Projects, Milan—on view through March 3—I had the chance to get closer to the American artist’s practice and exchange views on some of his key themes, such as social body monsters, idol formats, pathways. This meeting shed light on Flood’s poetics and relevance, while also delving into his collaboration with fashion.

On the occasion of Mark Flood’s solo exhibition “Battlefields” at Peres Projects, Milan—on view through March 3—I had the chance to get closer to the American artist’s practice and exchange views on some of his key themes, such as social body monsters, idol formats, pathways. This meeting shed light on Flood’s poetics and relevance, while also delving into his collaboration with fashion.

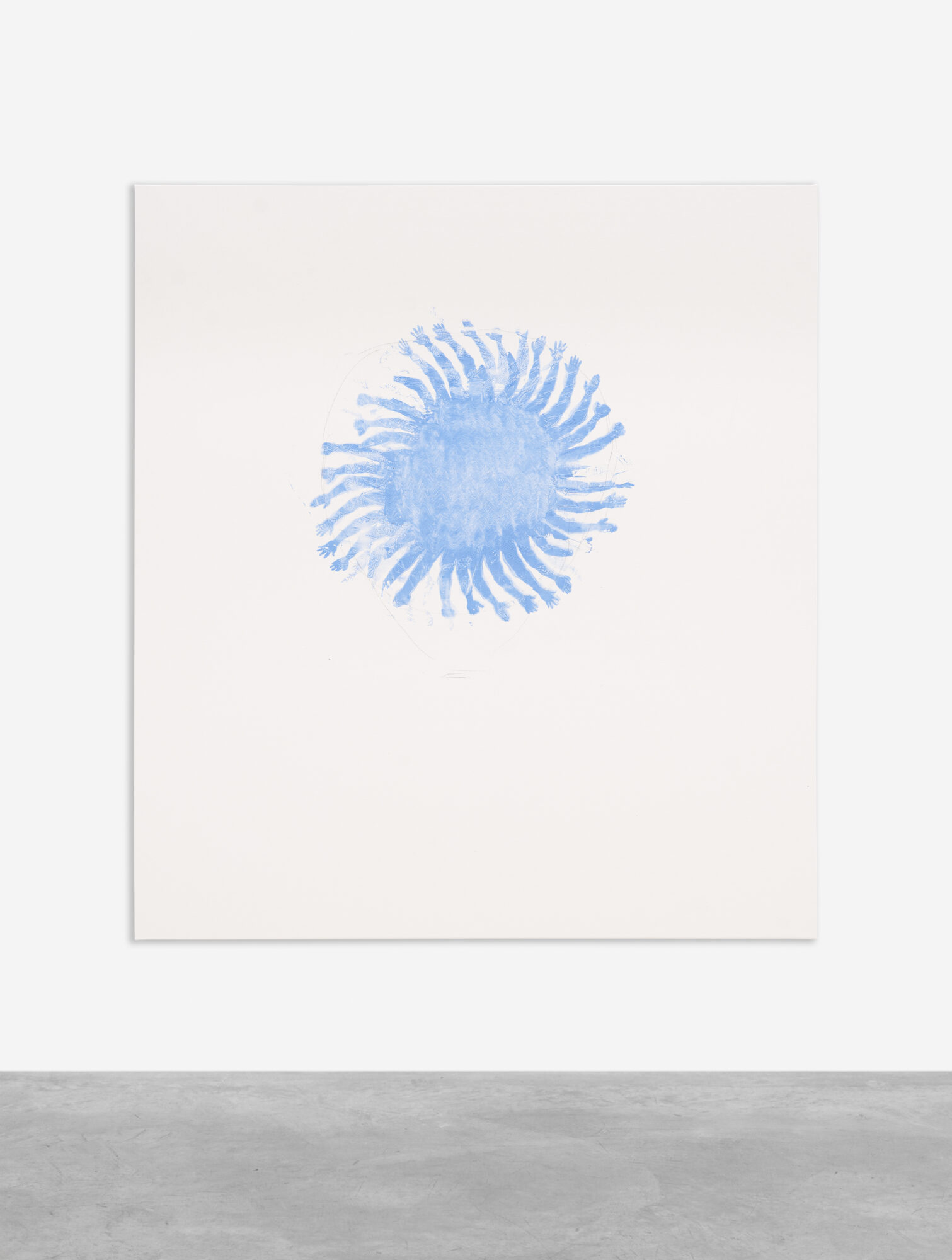

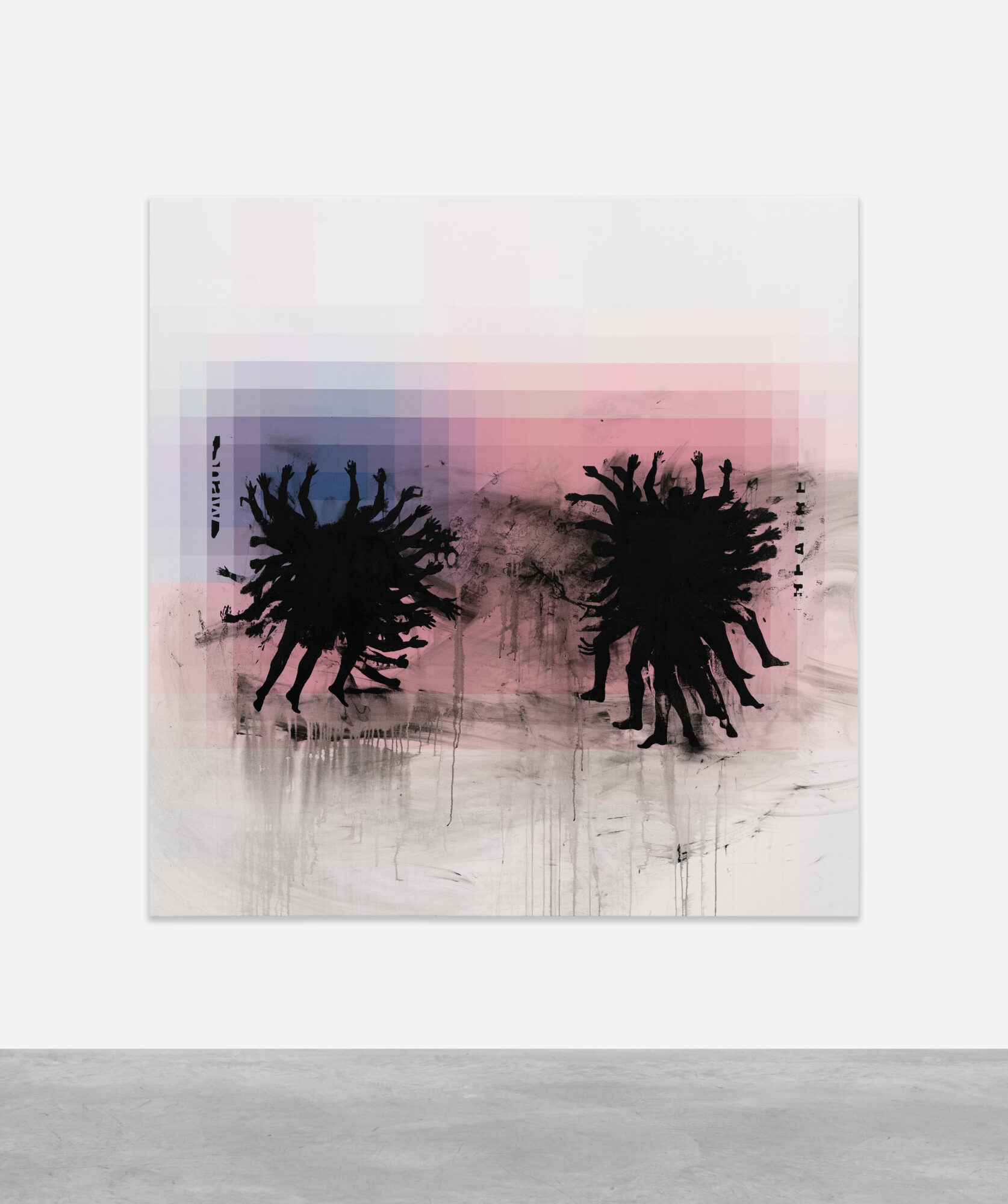

Martina Alemani: With “Battlefields”, and artworks Authority with Fuzzy Flag (2018) and Cannon Fodder (2022), you returned to social body monster paintings that you have been exploring since the beginning of your exhibition career in the 80’s. What meanings do they have in the contemporary?

Mark Flood: I like to think my silhouettes of the human body are a familiar referent to which no particular meaning is attached. I combine those body parts into monsters. Monsters signify intense episodes of violence in the human community, but again without being specific.

The works that you mention place monsters on top of one of my fuzzy U.S. flag paintings. So the USA is indicated as the place of conflict. There’s an idea of a contemporary civil war. I expect audiences could project any situation onto these images. I make meaningless paintings, but I hope audiences are stimulated to bring meaning to them.

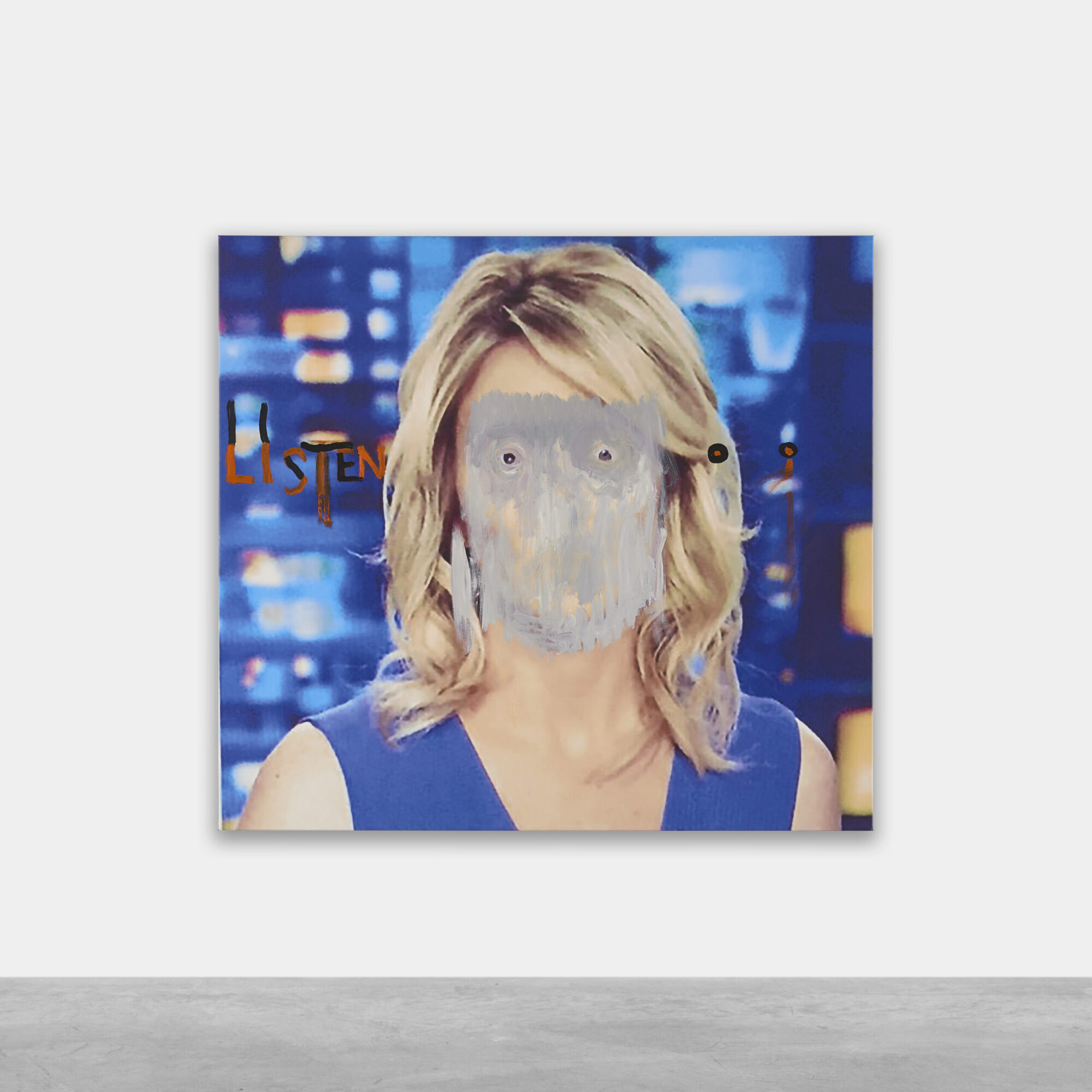

MA: In your brother Clark’s book Mark Flood in the 1990s (2022) I read a sentence that I think is a key to your work: “an idol, staring at you, whispering commands only you can hear.” This is something I can feel also looking at the work on display Listen (2017) where a CNN news anchor—as an authority figure—is obscured in her face by rough brushstrokes in gradients of gray, and the word ‘Listen’ hovers next to her head. Did you apply an “idol format” approach to the media?

MA: In your brother Clark’s book Mark Flood in the 1990s (2022) I read a sentence that I think is a key to your work: “an idol, staring at you, whispering commands only you can hear.” This is something I can feel also looking at the work on display Listen (2017) where a CNN news anchor—as an authority figure—is obscured in her face by rough brushstrokes in gradients of gray, and the word ‘Listen’ hovers next to her head. Did you apply an “idol format” approach to the media?

MF: Yes. I have been using the idol format for decades now. I took the idea from a book by Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. It was big in the 1970s when I was starting out. I don’t know how it’s viewed today.

Jaynes talked about the idol format: big eyes staring at you, combined with written or spoken commands to convey authority. It was just a tiny bit of his book. I have been milking the idea ever since.

It’s hard to find specific information about how images interact with our brains!

MA: On the last Milan Men’s Fashion Week, a collateral exhibition of your most signature series and trademarks motifs works (enlarged, pixelated corporate logos; irreverent stenciled catchphrases; and lace panoramas) was presented at Spazio Maiocchi—in collaboration with 1017 ALYX 9SM. How did the idea for this exhibition and the dialogue with fashion designer Matthew Williams come about?

MA: On the last Milan Men’s Fashion Week, a collateral exhibition of your most signature series and trademarks motifs works (enlarged, pixelated corporate logos; irreverent stenciled catchphrases; and lace panoramas) was presented at Spazio Maiocchi—in collaboration with 1017 ALYX 9SM. How did the idea for this exhibition and the dialogue with fashion designer Matthew Williams come about?

MF: Javier Peres of Peres Projects started the process by showing Matthew my work over the years. The first thing I did was tell them that they could do anything they wanted with my art; they could alter it in any way they needed.

ALYX had a lot of ideas and I wanted to get out of their way. I have done many collaborations over the years, in art and music, and I have learned that often its important to hold a space so your partner can do what they do.

I have friends who build houses. There’s a lot of creativity in building, but there’s also a practical side. People have to live in what they build. I always say I could never do that; I’m too irresponsible. I felt the same way about ALYX. People have to wear clothes! The functional dimension scares me.

So I let them do what they do, and I helped them on some technical issues. I was very happy with their choices, particularly with their focus on text paintings. I was amazed at how carefully they translated effects from my paintings onto the garments.

And I was honored that my paintings were placed alongside the runway.

MA: In lots of your works, you combine emptiness and meaningfulness. Why this grand ambition?

MA: In lots of your works, you combine emptiness and meaningfulness. Why this grand ambition?

MF: My art is like a pathway. I make it attractive in some way to lure the viewer down the path. I make the viewer think the art is about them, and they like that. But then they turn a corner and confront the nothingness of their existence. I thrust them into a void with vague spiritual overtones. It’s frightening at first, but then they like it. They find their reflection in the void of nothingness.

It’s like a ride at an amusement park. You think you might die but then it brings you back to safety. People like that.

MA: I quote another key sentence from Clark’s book: “Having dumped those feelings, I’ll allow that this scene has some charm.” Why do you think the viewer is so attracted to what you depict with dark humor and septic intelligence?

MA: I quote another key sentence from Clark’s book: “Having dumped those feelings, I’ll allow that this scene has some charm.” Why do you think the viewer is so attracted to what you depict with dark humor and septic intelligence?

MF: I think only some viewers are attracted by those qualities. I think it sometimes takes people a long time to get used to my art. I think a lot of people from my past were shocked that my art became successful because they had never taken it seriously. Dark humor… My work is funny to me and all my favourite artists are funny to me. But I have learned that there are many people who have no sense of humour.

MA: What has making art meant to you? I think a great achievement is that your works give the feeling of being timeless.

MA: What has making art meant to you? I think a great achievement is that your works give the feeling of being timeless.

MF: What is art? That is the question every artist is answering with their work. I have lots of ideas but I’m content to make the painting that hangs over the sofa, or over the bed.

I don’t care about timelessness, because I’ll be dead. I think the best way is to focus on the present.

Some people seek timelessness, and they use a Greek column or a spaceship. I think just walk down the street, see what people are actually doing. Most of all, what do they hang on their walls? There are signs and pictures everywhere. Ask yourself why.