Sara Piccinini. Time for Women!

On the occasion of the exhibition Time for Women!—on view in Florence at Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi until August 31, 2025, and dedicated to twenty years of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women—we spoke with Sara Piccinini, Director of the Collezione Maramotti, about the significance of the prize, the evolving trajectories of its winners, and the value of a journey through female creativity, research, and vision.

Martina Alemani: The Max Mara Art Prize for Women turns twenty, and the exhibition Time for Women! celebrates this journey at Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi. How did the shared commitment between Max Mara, Whitechapel Gallery, and Collezione Maramotti to support women artists begin? And how did the collaboration with Palazzo Strozzi come about—where, simultaneously, Tracey Emin’s major exhibition Sex and Solitude is on view?

Sara Piccinini: The Prize was born from Max Mara’s desire—as a brand always attuned to the universe and emancipation of women, and closely connected to art and culture—to support emerging female artists at a pivotal moment in their careers, offering meaningful support to develop their research and showcase their talent.

Whitechapel Gallery has historically been the first UK institution to present major exhibitions by women artists, such as Barbara Hepworth, Frida Kahlo, and Sonia Boyce. The Max Mara Art Prize was established in 2005 from a shared need to create a dedicated platform for women artists, who then—as now—faced greater challenges in gaining visibility and recognition in the art world.

Since 2007, the year it opened, Collezione Maramotti joined as the third partner: initially as the venue for the winners’ exhibitions and the custodian of their works, and later also as the organizer of the six-month residency in Italy, designed around each artist’s personal and artistic needs.

When we began planning this major anniversary exhibition—bringing together the projects of the first nine winners—we envisioned Florence as a key stop in the contemporary Grand Tour that inspired the residency. Palazzo Strozzi, where we immediately found alignment with Director Arturo Galansino, proved the ideal venue. The Tracey Emin exhibition had already been scheduled, but we were glad to embrace what felt like a fortunate coincidence—or serendipity—in presenting the two shows together.

MA: The residency in Italy is central to the prize. What kind of impact does this immersive period have on contemporary international artists?

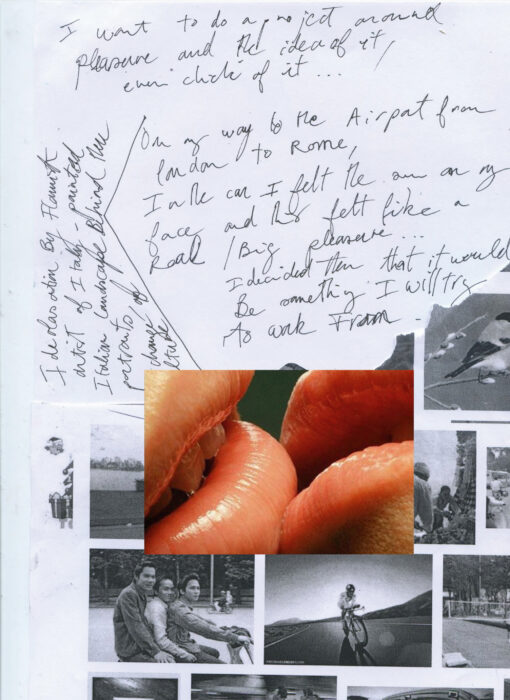

SP: Each artist has drawn from, explored, absorbed, and reinterpreted the wide range of stimuli offered by Italy. The country’s immense cultural, historical, scenic, artisanal, and human richness has fostered original and unexpected projects, never predictable in content or form.

I believe this experience has left a deep and lasting impression on all the winners: echoes of the research developed here, or of techniques acquired, continue to surface in their practices even years later. For Margaret Salmon, Corin Sworn, and Emma Hart in particular—who came with their young children and partners—it was a valuable opportunity to focus on their work without stepping away from motherhood, or to explore a different balance in family dynamics.

Italy remains a place many of them return to with pleasure, where personal and professional relationships forged during the residency continue beyond the Prize. In Emma Talbot’s case, it even became home.

MA: Are there particularly significant examples of how the prize has shaped the careers of its winners?

SP: All of them have built, and continue to build, impressive careers—and we like to think that the platform offered by the Max Mara Art Prize contributed in part to that trajectory. Following the Prize, they’ve gone on to receive major recognition and exhibitions—so many, in fact, that it’s difficult to single them out.

To name just a few: Margaret Salmon and Emma Talbot both took part in the Venice Biennale—the former in 2007, the latter in 2022. Hannah Rickards and Corin Sworn received the Leverhulme Prize in 2015. Andrea Büttner was a finalist for the Turner Prize in 2017, while Laure Prouvost and Helen Cammock went on to win it, in 2013 and 2019 respectively. Emma Hart and Dominique White have both exhibited at major international institutions.

MA: How do the acquisitions within the Collezione Maramotti relate to the Prize? In Andrea Büttner’s case, there was even a reverse kind of inspiration—she drew from works in the collection.

SP: During the residency in Italy—also because we host the winners’ exhibitions—artists always encounter our collection and its works.

Andrea Büttner’s case is particularly emblematic. Her interest in the symbolic dimensions of textiles and in Arte Povera—interwoven with a spiritual and monastic notion of poverty—led to a natural connection with works in the collection. She drew on the imagery and iconography of pieces such as Mario Merz’s magnificent 1988 table laden with fruit and vegetables, La frutta siamo noi (“We are the fruit”), or Alberto Burri’s burlap sacks, both part of Collezione Maramotti.

MA: Over the past twenty years, the prize has traced a wide range of artistic trajectories. What are the recurring themes and stylistic approaches that have emerged across the projects?

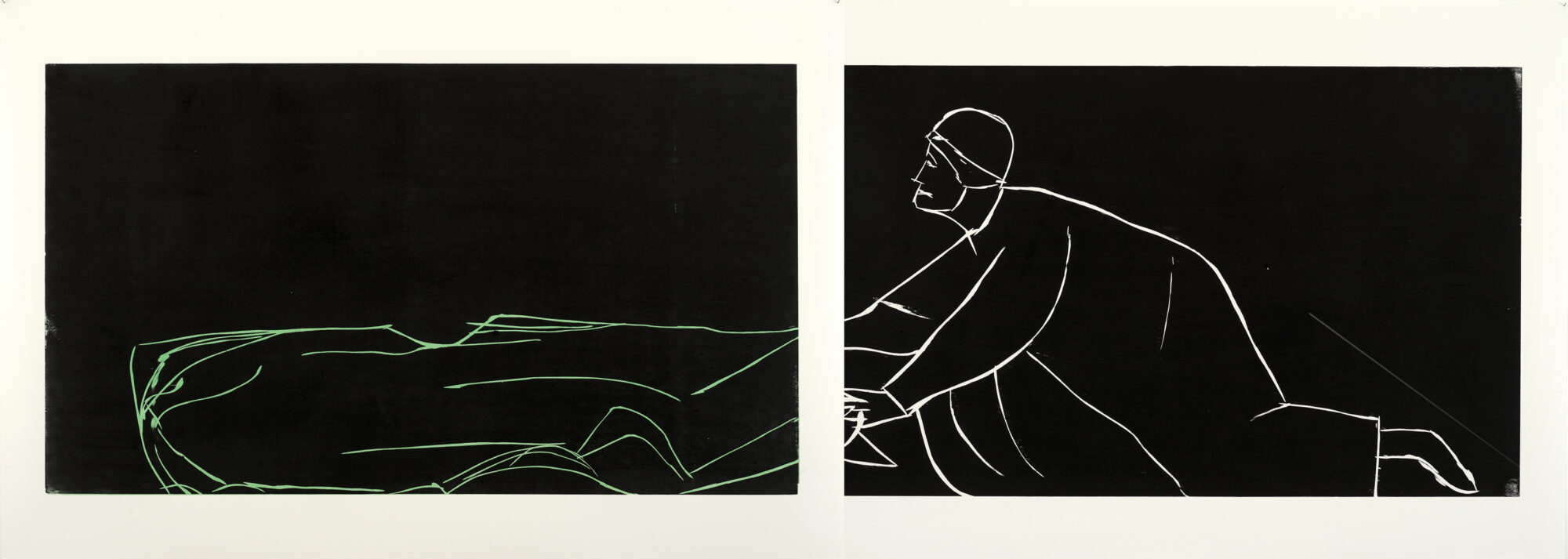

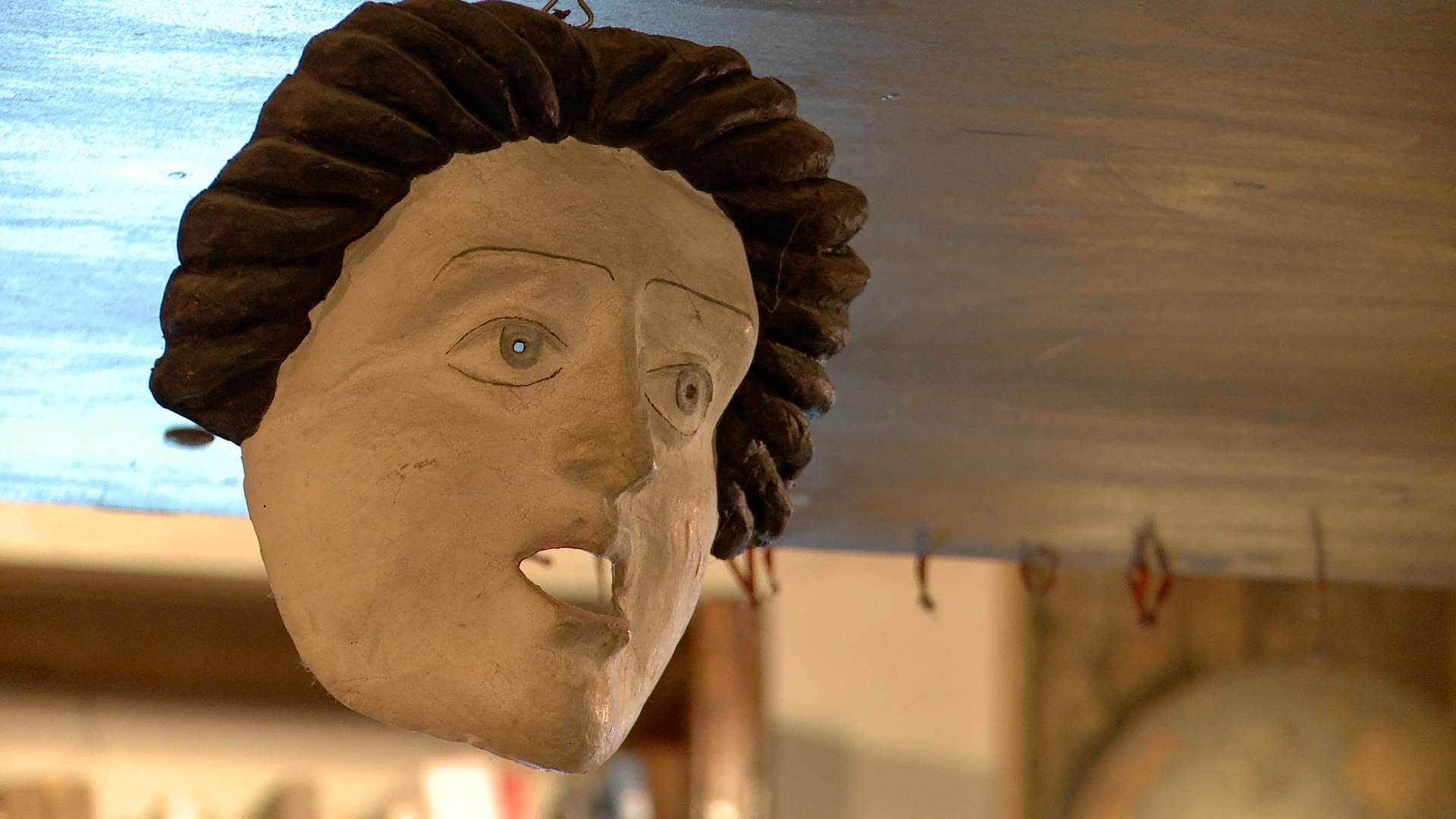

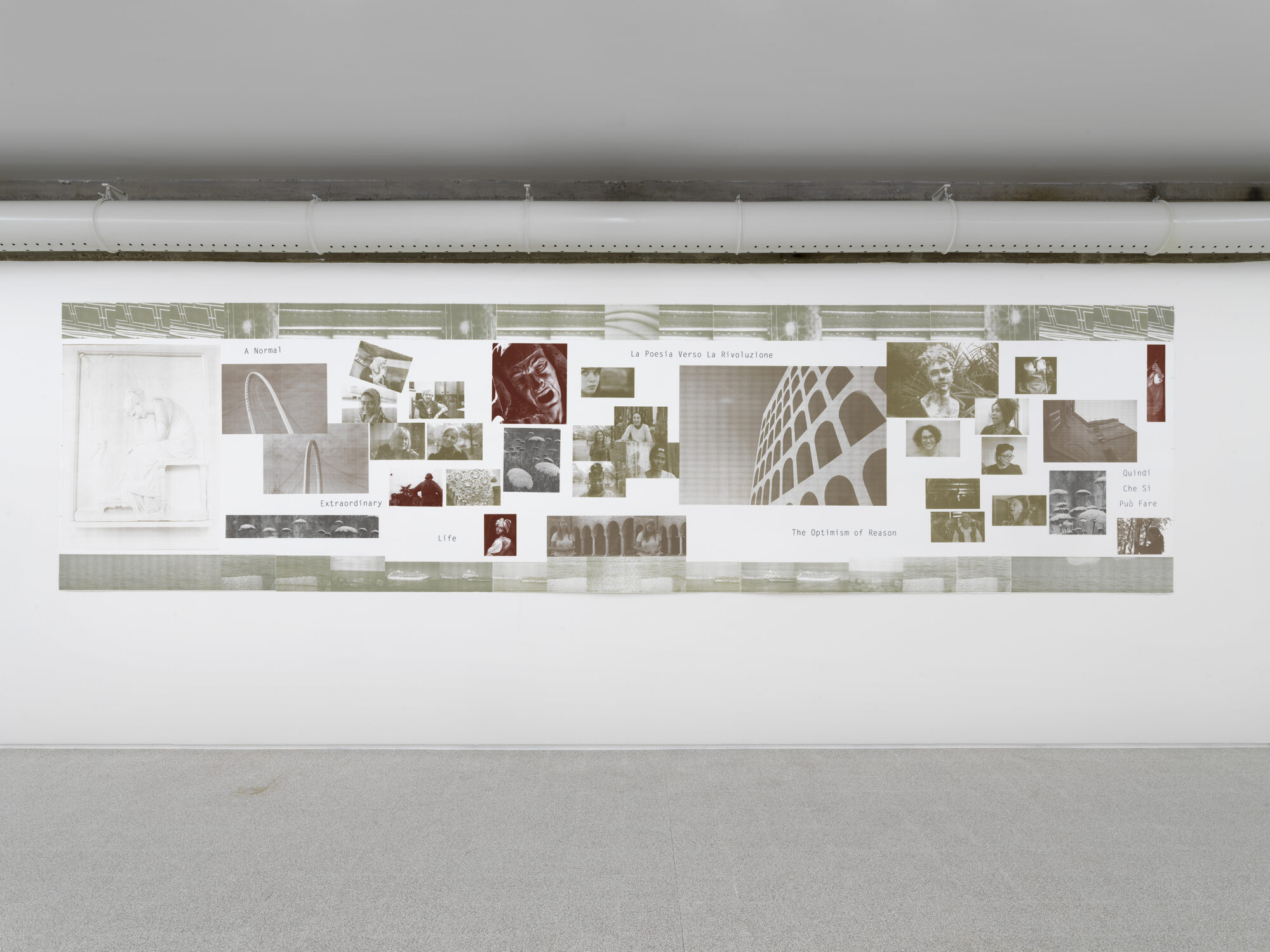

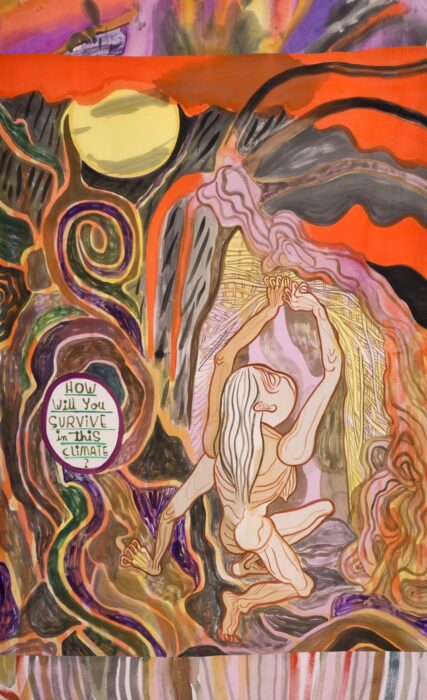

SP: Each artist has worked in distinct media and registers. This diversity of expression is particularly evident in the exhibition at the Strozzina, which brings together all the projects realized so far. We encounter Emma Talbot’s colorful silk paintings, three-dimensional sculptures, and video animations; the filmic works of Margaret Salmon, Helen Cammock, Laure Prouvost, and Hannah Rickards; Dominique White’s sharp iron sculpture; Andrea Büttner’s large-format woodcuts; Corin Sworn’s expansive installation of objects, costumes, and videos; and Emma Hart’s immersive ceramic lamp-heads, with rotating and electrical elements.

The themes range from the Commedia dell’Arte to the Labors of Hercules, from sensual pleasure to religion—some deeply rooted in Italian culture, others more universal. Recurring threads include the investigation of history (both personal and collective), memory, technical experimentation, gender roles and motherhood, the natural world, language, and narrative.

MA: Is there a common thread uniting these nine artists, despite the diversity of their media and poetics?

SP: While each artist brings a unique voice and approach, what they share is a powerful urgency to question dominant narratives, power structures, and entrenched cultural codes. Emma Talbot and Dominique White imagine alternative futures and dismantle patriarchal, capitalist, and colonial frameworks. Helen Cammock and Margaret Salmon place complex female experiences at the center, beyond idealization or cliché. Corin Sworn and Hannah Rickards investigate language, perception, and performance as tools for critical re-reading of the present, while Emma Hart and Laure Prouvost probe the limits of understanding and miscommunication, opening spaces of ambiguity and relational inquiry. Andrea Büttner, for her part, contrasts contemporary aesthetics with ethical and spiritual values in a reflection that also touches on the contradictions of the art world.

All of them, in different ways, challenge canonical representations of femininity—or themes traditionally associated with the feminine. The textile, for instance—historically linked to women’s domestic, professional, or artistic labor—becomes a conceptual field for Andrea Büttner, who foregrounds its symbolic meanings in historical and social contexts. Corin Sworn, by contrast, created costumes inspired by Commedia dell’Arte, which signal identity and social roles, while also serving as instruments of disguise or subversion.

Dominique White brought a forceful corporeality to her project, submerging large iron structures in the Mediterranean to oxidize them, resulting in the powerful sculptures of Deadweight.

Motherhood, gender, and family dynamics also recur—in Margaret Salmon’s Ninna Nanna, and in Emma Talbot’s The Age, where an older woman figure challenges normative ideas of femininity and fertility. Emma Hart integrated concepts from behavioral therapy into her installation, developed after researching family therapy techniques.

Hannah Rickards and Laure Prouvost both explore nature and language—though in opposite ways: the former with precision and conceptual clarity, the latter with imaginative and overflowing expression.

Finally, Helen Cammock, drawing on the baroque tradition of lament, gave voice to resilient and resistant women—activists, migrants, nuns, partisans, artists—figures too often hidden or forgotten, reclaiming history and offering alternative accounts of power, identity, and vulnerability.