Sunday at the Church. Other Spirituality, Other Community

Time and space are combined notions whose fragments are fully editable and replaceable. That’s why contemporary visual culture acts as an elastic space composed of chaotic moments which can be affected by continuous shifting in context. From past to present, from nonfiction to fiction, from the real to the paradox, these new artistic episodes open up new horizons shifting the directions of time, challenging memory and altering the balance between self and collective expression.

Time and space are combined notions whose fragments are fully editable and replaceable. That’s why contemporary visual culture acts as an elastic space composed of chaotic moments which can be affected by continuous shifting in context. From past to present, from nonfiction to fiction, from the real to the paradox, these new artistic episodes open up new horizons shifting the directions of time, challenging memory and altering the balance between self and collective expression.

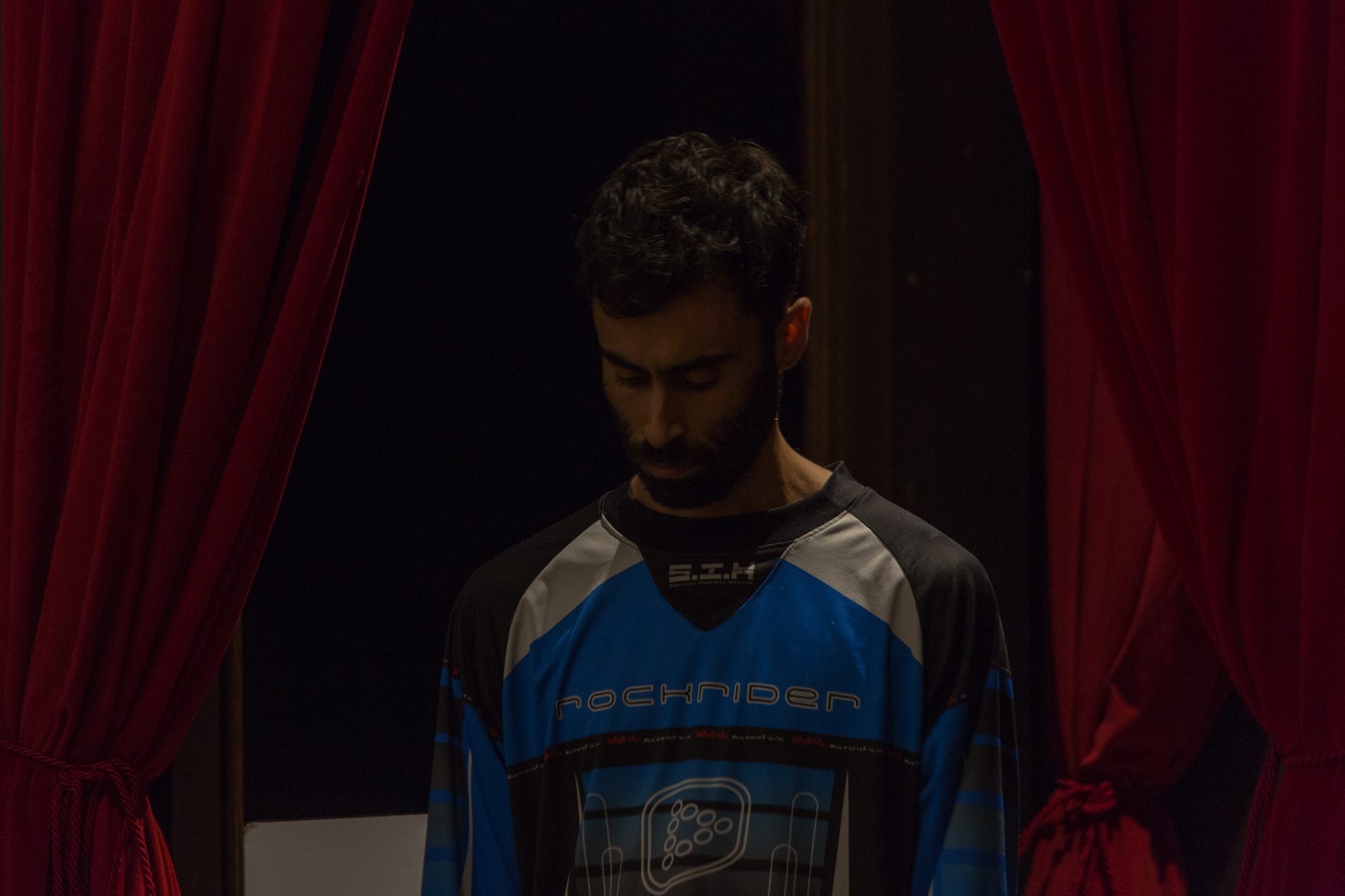

On the occasion of the last appointment of “Time, forward!” – VAC Foundation’s Public Program curated by Giulia Morucchio and Joel Valabrega at the Venetian ‘Chiesetta della Misericordia’ – Amsterdam-based, Italian choreographer and artist Michele Rizzo presented an adaptation of Higher xtn, a performance he has been performing since 2015.

This time was not just about re-staging an aesthetic object in a new context: a club in a museum or a party in a sacred place. Even if the operation is clear, precise and not even complicated – a variable number of performers dancing a techno piece by Lorenzo Senni – the conceptualization of the work itself is far from being so simplistic, and it rather describes an imaginary migration that makes gestures become vehicles and the bodies archives.

Drawing a correlation between classic clubbing aesthetics, as well as gesture drawn from ritual dance alienation, Rizzo’s Higher weaves a powerful dramaturgy that relates to contemporary sociality and its tension between self-expression and new communities.

What follow is a conversation with the artist, starting from this last Venetian variation of Higher xtn.

Stefano Mudu: I would start this conversation speaking about the spaces and frameworks that, in its various formalizations, Higher has involved so far. The performance experienced a series of migrations that go from the profanest space – the club – to the most sacred one – a church – even if desecrated. How did you approach different spaces? Do you think Higher gained meaning from this shifting?

Michele Rizzo: Higher comes from a specific period of my life as well as a peculiar place: the club. It was the moment of an immersive series of experimental researches and I used to spend my time in those spaces following a ritual that I enjoyed a lot. With other rhythms, it’s something I keep practicing and believing in.

As a dancer, performer and choreographer I have always been tied to body gestures, but dancing in the club made me aware of another, and completely new, movement education. So, this is the background where I thought about the first migration. I tried to bring my experience outside the dance floor reenacting it into the studio; let’s say forcing the performative object from its original space to a much safer, and even more protected, environment.

Actually, the experience was traumatic and represented a general desecration. In fact, the way they are generally conceived, clubs and discos produce an overwhelming experience that goes beyond spatial or acoustic conditions, and achieve a perfect balance set on a lot of parameters. Artist studio does not. The main reason that drove me into Higher research flow, was the necessity to relate these two movement approaches: the first one belongs to a strong and underground social context led by Dionysian feeling; the second, more institutional and controlled, looks at body language as the grammar of an art form.

Then a second important transition happened in theatre. The occasion featured three dancers only, a frontal execution, an audience, and was strictly organized in term of timing and setting, which made the space a black box. Let’s say that it was even more desecrating than the original context as it seemed extremely classic.

Thus, the most important migration was to museum. And it was not only thanks to the space, but also because it helped me to understand that Higher was appreciated from the art spectator even more precisely than from the theatre’s one.

My approach to dance is particularly meditative. I work with movements that are internal activations, and quoting Renaud Barbaras, my dance is a sensation of self-expression obtained by impression. That is why I believe that theatre audience, acting as a whole body which does not preserve individualities, represents a spectator who is difficult to deal with. On the other hand, I guess that museum audience manages each spectator’s individuality even when it is supposed to collectively occupy the space.

At Stedelijk for instance, working with a wider group of performers in a three-dimensional space, gave me the possibility to break down the usual theatrical frontality, and to work on four different sides.

Finally, having the possibility to show the piece in a church was a great chance to give me another realm to explore. I think clubbing culture has a kind of profane spirituality, not only aesthetically speaking, so this last migration loaded the performance with new meanings. Since the first studio experience thus, each context variation has also described a different social group that develops a sort of devotion towards its peculiar objects. In general, I like saying that Higher gains new pieces or opens new imageries each time it is shown. I imagine its movement as an infective agency or a virus that invades living contexts by using and contaminating them.

SM: Staying in the talk, I would insist that the smartest consequence of this migration lies in the concept of community. Would you speak about your idea of dancing in the community – or with it?

SM: Staying in the talk, I would insist that the smartest consequence of this migration lies in the concept of community. Would you speak about your idea of dancing in the community – or with it?

MR: On a choreographic level, the score is based on two simple principles: it deals with preserving an individual dimension and to be part of a community at the same time.

During rehearsals, I always invite my performers to experience the entire choreography as a useful journey to reach their inner self. Finding a balance between being concentrate while performing on public stage, is indeed the main effort in Higher. Performers need to focus on movements while they are addressing the spectator with a precise and firm self-expression.

By default, this attitude produces an energy that goes beyond the individual and embraces the group. That is to say, there is no clubbing without a community (and vice versa) but also that clubbers must pursue their own sensitivity to be part of a group.

Physics defines quantum superposition state as a principle that controls any system made of a combination of possibilities preserving their autonomy despite their general configuration. I guess this assumption well describes my idea on clubbing experience: a context in which is possible to preserve one’s individuality and sharing it at the same time. I find this condition particularly rare in everyday life.

SM: Let’s describe Higher choreography: each performer enters the space alone, complying with its sense of rhythm and respecting Lorenzo Senni’s music. As the beat starts increasing, then all the performers coordinate and find a way to dance together. Following the climax, individual bodies become one. I find many similarities with the aesthetic of rituals or folk dances. Do you think that clubbing dance still has something to do with these vernacular dimensions of togetherness?

MR: I have never directly experienced folk dance and since my work relates to a personal involvement, I just considered that Higher might have something to do with a certain kind of folklorism. They are both handed down through generations in situ, for instance, and I remember that when I started working on Higher I was also looking at Gurdjieff Sacred Dance for its effective unison and mutual balance.

Even if it has something related to rituals, Higher refers to a specific style danced by people I used to look at in Amsterdam. They were dancing the Shuffle dance, a series of movement obtained mixing different styles such as Merlburn Shuffle, Konijnendans (rabbit dance) and Gabber (a specific movement danced on hardcore music in Rotterdam during Nineties).

The style I was referring to was a choreography with very strict rules and steps that has passed down over many generations of clubbers becoming an element of cultural unification as is evident in documentaries such as Fiorucci Made me Hardcore (1999).

Although there was no effective grammar for these movements, the current clubbing gestures are completely different to those practiced when I started working on Higher. The vocabulary has evolved and sometimes crystalized in a very local way: for example, there are many differences between Berlin’s variations to those in Amsterdam. Or even, until a few years ago, dancing with feet and legs was much more common than planting feet in the ground and working with arms, as it is today.

When you think about it, this vocabulary has a sort of liturgical value eventually.

SM: Thus, we could also consider Higher as a platform for recording gesture variations in the clubbing scene.

SM: Thus, we could also consider Higher as a platform for recording gesture variations in the clubbing scene.

MR: We could, potentially, even if my aim has never been to create a historical repertoire. All the movements in the performance pretend to be an interpretation of the originals but I couldn’t ever record their precision. Rather, it is an out-of-time discourse through which I am interested in defining dance as an artistic material, in the same way a sculptor uses clay.

Actually, I would also say that dance is a raw material that, along with the body, creates a kinesthetic identity; something that goes beyond appearance, connects with a complex energy and engages each dancer in a peculiar way. I mean dance as a sculptural agent.

SM: Your body’s clay sculptures, for instance, remind me the same Higher trance sensation.

MR: I have always carried out sculpture and choreography in parallel. What really fascinates me on both levels is the synergy between materials and action. In-between these moments, there is an external and pervasive energy I feel I can connect to, and any outcomes of this trance state, sculptural or not, contains much more fluidity than we think.

After Higher, I worked on other two theatre projects, which I then gathered in a purely conceptual trilogy. Spacewalk (2017) is conceived as a transition of spaces, or an investigation over the space of trance. It is probably the representation I wanted to give to the agency I have just finished talking about, in which I have the chance to consider the watery dimension of my editable identity. The following project, Deposition (2019), it is an attempt to study the effort of returning from that state and re-embracing a tangible existence.

Once again, I stole a term from physic: science defines deposition as a transitional state in which, after specific changes, materials deposit creating new surfaces.

As in a perpetual change of state we exist on a spiritual level, but we manifest ourselves in physical way which is far from being immanent. Intuitively, I tried to bring these two realms together and I am quite sure that my interest in sculpture come from here: it is the effort of crystalizing something that is always constantly bubbling.

SM: This liminal state is also experienced by the spectator to the point that I felt engaged by performers’ gaze and I wondered which kind of boundaries you wanted between performers and audience.

SM: This liminal state is also experienced by the spectator to the point that I felt engaged by performers’ gaze and I wondered which kind of boundaries you wanted between performers and audience.

MR: Part of my research employs alienation processes as moments to reach a meditative distance from reality. But a fundamental element recalibrates this position and asks the performer to develop an external contact with the audience.

During rehearsals, I always encourage my performers to engage the audience as if they were looking out a window; I want them to feel like they belong to a double space, giving importance to both. They have somehow to find their way to embrace a clear perception of the world by taking distance from it.

An important reference to me has been Thought in the act (2014), a book by artists-researchers Erin Manning and Brian Massumi. In its first chapter, Coming Alive in a World of Texture, they reverse classical studies claiming that the neurotypical perception of the world is much less sensitive than that of an autistic person. In particular, they assert that, while the neurotypical brain tends to isolate the object of its attention from the context in which it is included, the autistic brain does not operate this way and rather removes any sort of hierarchy making the entire context uniform. According to Manning-Massumi, for instance, the autistic brain has much more sensibility in empathizing ecological problems.

Aside from this psychological specificity, this assumption drove me in defining my own imaginary. In particular, I believe that developing a multichannel perception is a necessary tool that the self needs to be aware of.

SM: All these energies go hand in hand with a kind of gender-free eroticism they infuse. I don’t know if I am right, but this feature makes your performances intriguing, combining struggle and loneliness as well as a performative freedom of sexuality. What is your take on this?

MR: What we do with Higher is to get naked in front of the audience. But this is an investment that goes beyond a classical expression of sexuality and rather represents a self-engagement. So if ever there was something erotic, it would surely be autoerotic.

Moreover, ecstatic dancing generates a personal physical pleasure both in movements and rhythms. It also gives the sense of fluidity you asked about while describing that general sensation of watery body.

I had different feedbacks similar to yourse. But I guess that behind this perception there is an absolutely unpretentious gender-free eroticism, or there is no desire to be naughty.

Indeed, the body is a sexual object but erotism is internal at the same time. Dancing is a self-stimulation matter.