Under Trial | The 79th Venice International Film Festival

The just concluded 79th Venice International Film Festival shed light on an existence, ours, fully on trial. This text gathers first-hand impressions and attempts a synopsis of the main narrative trajectories that ran through the kermesse. Between courtrooms, emancipated children, rapacious love affairs and unprepared parents, this year’s cinema dares to unhinge taboos too often inviolate.

It is now since 2016, with the only exception of 2020, that I have been following the Venice Film Exhibition with uncanny willingness. My attendance at the kermesse has undergone a silent mutation over the years: the feverish enthusiasm has gradually turned into an unflappable acceptance of the rules of the game. A game of endless queues, steamboats, crowds, exasperated air conditioning and, finally, film. The film comes at the end of a maelstrom of resistance that discourages the misguided or disinterested. Having passed the cyclone, the show reveals all the coplanar trajectories that pass through it: stars, journalists, students, photographers, make-up artists, onlookers, Venetians, tourists, waiters, cleaners, security, police, masks, each one transits and leaves its own trails.

The settling in this year was longer and more apathetic than usual, emotions struggled to meet my skin. Because this year was an exhibition of processes. Processes to the real, to the imaginary, to history, to culture, to identity. And processes are known to be long-lasting and need patience, hope and tenacity. In the end, they show their worth, and never before has this year’s judgment elicited mixed feelings. Rashly opinions from critics and more generally from the press struggled to meet, disagreement was the most vibrant sentiment on screening days. There were those who loved Bardo (Alejandro González Iñárritu) and those who loathed it, those who praised Blonde (Andrew Dominik) and those who flunked it, those who felt goosebumps for The Whale (Darren Aronofsky) and those who were bored. Never have I witnessed such divided impressions. But this need not be read as a bad omen; many films presented in Venice will no doubt arouse the curiosity of many once they are released in theaters and on streaming platforms.

One thing that does not change, however, is my controversial relationship with the Golden Lion, Laura Poitras’ All the Beauty and the Bloodshed on Nan Goldin. It is customary for me to miss it. And that was the case again this year. (The bad luck is such that it was one of the three films in competition that I had to skip). Consequently, my focus will not be on the work of Laura Poitras, whom most may recall for her admirable work with Edward Snowden in Citizenfour in 2014. Instead, my narrative will attempt to weave together some of the thematic paths that ran through the exhibition. If last year it was the masculine, as gender, idea and body at the center of an expanded reflection, this year the process of the real takes on more articulated shades. On one hand, it literally takes place in an assize court, see Lord of the Ants (Gianni Amelio), Argentina 1985 (Santiago Mitre), Saint Omer (Alice Diop), and also commendable of mention is The Kiev Trial (Sergey Loznitsa) presented out of competition; on the other hand, it affects figures and postures that are undergoing a strong redefinition today, such as parenting, couple, gender, and identity. The family, in its most cannibalistic forms, serves as a backdrop and equally as an object of investigation. There is a widespread narrative sensibility interested in tracing those atavistic ties that unite and separate us to the Other, and enable existence. An existence no longer marked by idylls or conciliatory motifs, but rather raw, critical, sometimes unbearable.

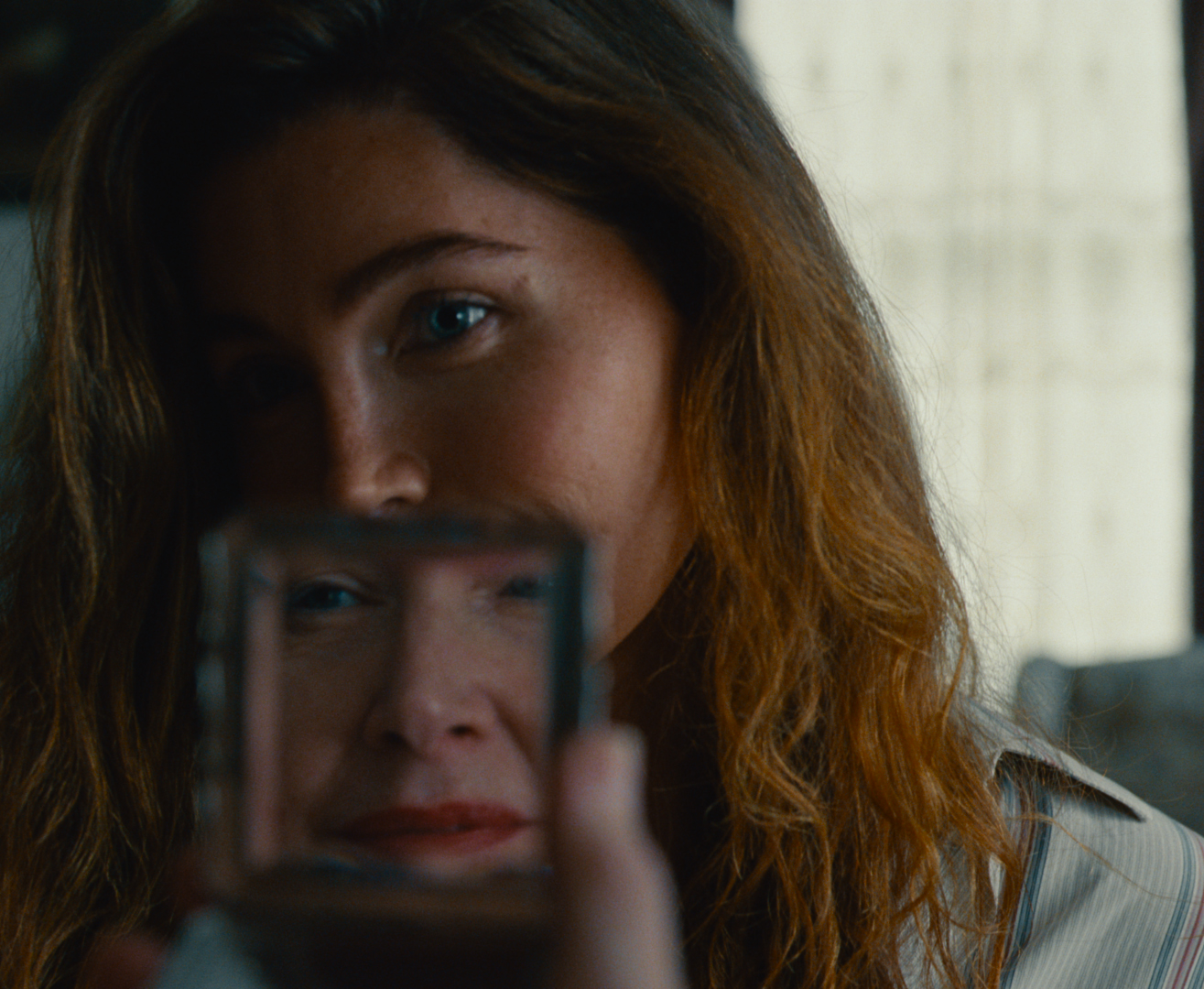

The Eternal Daughter (Joanna Hogg), The Son (Florian Zeller) The Whale (Darren Aronofsky), Love Life (Kôji Fukada), Other People’s Children (Rebecca Zlotowski), and Monica (Andrea Pallaoro), all of these films descend inside the black cave of the parent-child relationship with a lifeline that struggles even to support the weight of a glance. But each film is also something more. Monica for example is also a homecoming, silent and intimate and lacerating, and in some ways reminded me of It’s Not the End of the World (Xavier Dolan). It is also a film about trans identity, with a wonderful Trace Lysette, already admired in Transparent and Disclosure. Emanuele Criolese’s return to theaters also insists on this theme, with an autobiographically tinged drama, Immensity, where the viewer helplessly witnesses the troubled adolescence of Adriana, a young girl who rejects her own femininity and calls herself Andrea, a name that preserves a gender neutrality that allows her to experience her own residing masculinity. Amelio, too, places uncomfortable identities at the center, staging a dignified portrayal of the sad story of intellectual Aldo Braidanti and his young lover that will lead both to a painful end. In the background remains etched a homophobic and provincial Italy that is still occasionally scary today. And no less is Guadagnino, another Italian, who crosses queer thresholds to the point of pushing into an aesthetic cannibalism of love, so powerful that it ends with ingestion, an absolute form of acceptance, absorption and synthesis of the dying lover.

The Italian landscape is thus suddenly responsive to the narrative of the different, and in a surprisingly captivating way. It is as untimely as it is exciting this newfound drive. Let us hope that the fire is not already dying out.

In addition to these noteworthy Italian films, two others impressed me: The Whale by Aronovsky and The Banshees of Inisherin by Martin McDonaugh. The former because it comes close to breaking the audiovisual limits of cinema. The constant sweat, the garbage everywhere, the greasy, greasy food, all lead to a feeling of disgust that absorbs the room even on an olfactory level. Aronovski managed to trigger a reaction that made me aware of the medium I was immersed in and its limitations. Add to that an Oscar-worthy performance by Brendan Fraser, an extraordinary nurse (Hong Chau), and a camera that doesn’t come out of an apartment door. (Or rather it goes out, but only to go back in). This movie deserves attention.

The latter, The Banshees of Inisherin, on the other hand, deserves credit for truly remarkable writing (in fact, it won the best screenplay) and for characters created with a love of detail that really hits home (Volpi Cup for best actor to Colin Farrell). The parent/child or lover relationship gives way this time to friendship and brotherhood. The sensitivity with which McDonaugh captures the eccentric characters who populate this small Irish island is touching. Also to be commended is the fact that the film continually oscillates between genres. Drama, comedy, thriller alternate as in a masquerade ball.

Finally, it deserves a note, this time negative, Blonde, which reduces the complexity of a figure like Marylin to a projection so superficial as to annihilate her. No narrative line is deepened, and every path is only sketched out so that an innocent, naive, passive, but successful silhouette emerges. The daughter-father complex is trivialized and makes the whole film like its final scene: an obscene fellatio that was better avoided.