Untitled 2020. A Way to Recover One’s Own Journey and History

This exhibition (Punta della Dogana, Venice, through December 13th, 2020) comes at the right time bringing some thoughts: from space appropriation in a museum, to the idea that we can live in beauty and integrity. There are artists who have an interesting proposal and who have been able to create their own world, and artworks that remind us to think about our body and our role in the world – without overlooking the universal experience of death, as well as sex.

This exhibition (Punta della Dogana, Venice, through December 13th, 2020) comes at the right time bringing some thoughts: from space appropriation in a museum, to the idea that we can live in beauty and integrity. There are artists who have an interesting proposal and who have been able to create their own world, and artworks that remind us to think about our body and our role in the world – without overlooking the universal experience of death, as well as sex.

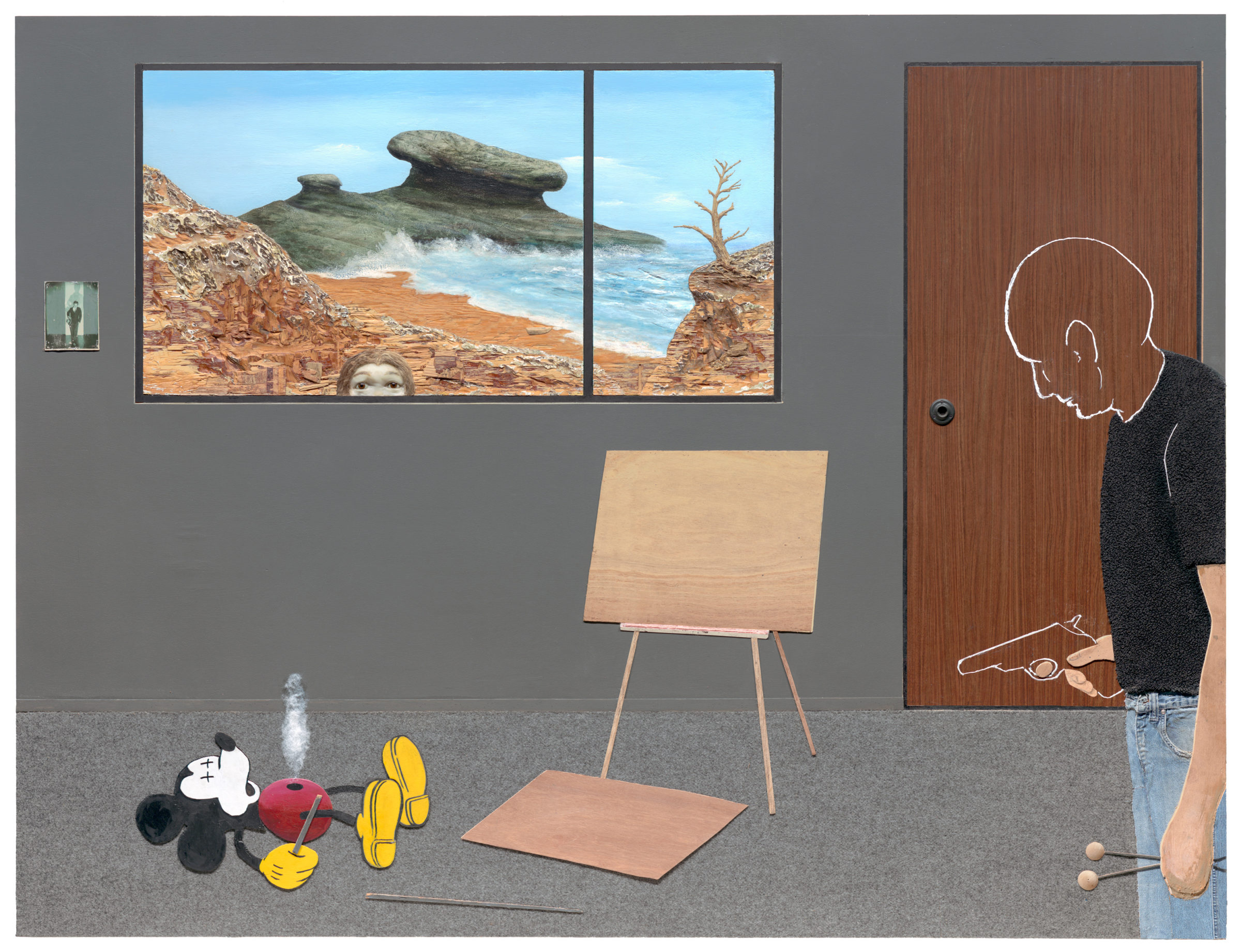

Martina Alemani: You decided in the beginning to set up right in the Cube of Tadao Ando one of the room somewhat modeled after one in Thomas Houseago’s studio, that is used for reflection, planning, researching, musing, playing with images and let the ideas take shape. I liked Helen Molesworth’s sentence – from a conversation with the three of you, part of the exhibition’s catalogue – ‘Whether it’s words or objects the question is what are you going to do to keep that aliveness going?’, I am also the one asking.

Caroline Bourgeois: The place is first of all very cosy… library, sofa, computer, music, and so it should make you want to stay there. I think the public will be

surprised to discover a much more private space, by visiting a museum. There’s a lot to see between the videos and photos, plus the works as in progress of Thomas Houseago. Finally, we are training the guard and pedagogical teams, in order to invite the public to appropriate the space, use the walls to play with the images of the works, consult the books, etc.

Muna El Fituri: The exhibition is very dense, at times shocking. We all felt that most of the time, the museum experience does not provide an oasis of relaxed reflection. We are hoping that the public will experience more connection by taking a breathright in the heart of the museum. Being able to read or think or research in the moment could reposition one’s relationship to what a museum visit feels like. It’s both a pause / a breath if you will; and a way to stimulate and reignite. In yoga breathing, this would be the Kevala Kumbhakabreath in Pranayama I suppose.

Thomas Hauseago: Ando’s central cube is modelled on the drawing room at our studio: it’s practically the first space you come across on entering the studio. It has become a social, collective and fluid space where we eat, talk, listen to music, plan and process, and where we have friends to visit. It’s a room that has become more and more important for Muna and me. It was largely conceived by Muna and I think it represents the opening out of the studio into the world, in a broader sense of creativity and free thinking and also a place of refuge. Years ago Muna suggested to me the idea of doing research through images to create a form of personal and artistic archaeology – a way to recover one’s own journey and history.

This idea also operates as an archive to visually tell complex stories. This has evolved quite rapidly into a wall of images that is constantly moving and transforming as we have worked on it over the years. In the cube, we wanted to open this mode of research and visual thinking to all visitors to the exhibition and open our own references and lines of visual thought. The room represents transitional space between outside and inside, past and new ideas, where creativity meets life. I think this is part of the “aliveness” that Helen so beautifully describes. Here, the studio becomes more than just a place where objects are made – it is a place that fosters a creative community, a kindof “breeding ground” for connection, healing, safety as well as newideas. We wanted to offer something of this in the show – it was important for all three of us that the exhibition was generous.

MA: Molesworth says that when we find other words we do not get to be the same as we were. Are we facing a time in which it is fundamental to find a name to the current wave of contemporary art? (El Fituri admits “this triggers so much psychology. We’re at this weird cusp moment in which we see the oppressive father, the oppressive patriarchy, which is exactly when the killing of the fatherneeds to happen, right?”). Is it necessary to define in an unique way the various contemporary artistic experiences? For example, is it possible to give a name to the current wave in contemporary art?

MA: Molesworth says that when we find other words we do not get to be the same as we were. Are we facing a time in which it is fundamental to find a name to the current wave of contemporary art? (El Fituri admits “this triggers so much psychology. We’re at this weird cusp moment in which we see the oppressive father, the oppressive patriarchy, which is exactly when the killing of the fatherneeds to happen, right?”). Is it necessary to define in an unique way the various contemporary artistic experiences? For example, is it possible to give a name to the current wave in contemporary art?

CB: It seems that we are in a period full of questions and questioning on issues and policies, environmental, identity, value. In the Anglo-Saxon countries, the so-called minorities, blacks, women (actually the majority), are much more exposed in institutions, giving a new possible reading of art history. The same questions are also asked in some European institutions (e.g. the Black Model at the Musée d’Orsay, Lynne Cooke’s Outliers) and different voices are heard. What we are trying to do in this exhibition is to allow for this to happen in a variety of ways, trying to offer an experience rather than a demonstration, which evokes subjects of history, philosophy, and the body.

MEL: I agree with Caroline, this is time for questions, open-ended questions, expanding the rules,stretching the boundaries. It is time to shedlabels and stop qualifying positions in binary terms such as center and fringe, metropole and overseas, White Male and Other. One of the ways to achieve this is that most of the discussions about what still qualifies as Other are conducted by those very Others we are talking about. The idea that there is still a “White Male Artist” is obsolete in the 21st century. Now it doesn’t mean the balance of power is faira nd equitable. On the contrary – we see a resurgence of class disparity, inequality, racism, sexism, xenophobia around the world. I like to think of it as the last gasp before its certain death.

TH: I think Muna is right when she says that art is, out of necessity, returning to its fundamental purpose of inaugurating new ways of thinking and therefore of living. In this dynamic, it fosters social change and challenges what is possible. Clearly the world is once again at a crossroads where that old toxic patriarchal system is once again ready to destroy us and cause us all unnecessary chaos and pain. I like the idea that art and creative thinking can open different channels and paths on how we move forward and refresh our social roles. With a broader notion of art, we can keep reclaiming the connection between all forms: music, dance, film, poetry, acting, healing,philosophy, etc. Through this bigger sense of art and connection to a greater sense of audience, we create relationships and bonds that allow for inner and outer healing that in turn always leads to social change, and the idea that we can live in beauty and integrity.

MA: Caroline Bourgeois speaks of layers that you are trying to put in one art movement at a time, by adding artists from younger generations and unknown artists, “because no one has all the answers” and you wanted to take an artistic risk by presenting to the public a sensitive and sensory approach to contemporary art. How you all together questioned these choices? The dialogue is interesting also when talking about the forms you chose – for example a sculpture presence in the form of drawing in the case of Henry Moore – as well as the subjects you used and the way of installing the huge number of artworks.

MA: Caroline Bourgeois speaks of layers that you are trying to put in one art movement at a time, by adding artists from younger generations and unknown artists, “because no one has all the answers” and you wanted to take an artistic risk by presenting to the public a sensitive and sensory approach to contemporary art. How you all together questioned these choices? The dialogue is interesting also when talking about the forms you chose – for example a sculpture presence in the form of drawing in the case of Henry Moore – as well as the subjects you used and the way of installing the huge number of artworks.

CB: We know each other very well, and for more than 10 years we have been talking about art every time we see each other. The discussion went quickly at the expense of a greater risk by not including testimonies from a sculptural point of view like Giacometti or Brancusi (but books in the library), to move towards more unexpected artistic proposals. For example, in the first room that we named STANDINGwe find Valie Export, Teresa Burga, or Magdalena Abakanovitch; artists that we don’t see often, but who have an interesting proposal and an interesting place because they created their world. For the choice of Henry Moore’s drawings, it was immediately evident to us, to talk about this moment of the Second World War, what can an artist do? He made his drawings in the London Underground where people were hiding to avoid bombs… These works are related to another artist in Los Angeles who is very important to us, Paul McCarthy, with a work that evokes Henri Moore, but instead of a woman lying down the woman’s trunk is vertical, so the question of standing is almost as much physical as philosophical.

MEF: What we need to do is look at works as works, the only difference between a known artist and an unknown one is their market value and their ability to live off their art. It doesn’t say much about the importance of their work. I’d like to think of it as an engagement of all your senses, your intellect, your spirituality. This goes as well for the compartmentalizations, the artificial divisions between media, “sculpture,” “painting,” etc. When is sculpture? When is a sculpture born? When the object is made? When the idea springs? When a drawing is made by someone who expresses themselves in 3D objects? These are the kinds of questions we’d like to raise. The titles we chose for the galleries are largely intuitive. They are designed primarily as a prompt, a fil conducteur, something you can use to orient oneself spatially or to contradict, to react.

TH: What we immediately realized is that this show has been germinating for a long time in the many discussions that the three of us have had over the years. The show is really the result of a broad and on-going discussion we have about the purpose and freedom of art from academic and restrictive labelling. For the three of us, art is an integral part of the way we choose to live every day and we wanted the exhibition to have this notion at its core.

MA: How did you solve the matter of the constriction of space for each piece? The trick consists in the right dialogue between artworks?

MA: How did you solve the matter of the constriction of space for each piece? The trick consists in the right dialogue between artworks?

CB: We wanted a generous exhibition and a more intimate relationship with the public (we replaced the benches with chairs), and we also worked very visually, using the blackboard in the studio to position and discuss the works. There is a part of intuition in hanging, and a part of experience and place, and the works we chose.

TH: Caroline is a curator of extraordinary vision and her deep understanding of space has been essential. We discovered quite quickly that by letting ourselves flow in a kind of process of reflection, the works found their spaces and relationships very easily. The more we relied on the intuition and wisdom of the other, the more naturally the works found their space, and we realized an abundance of themes and connections that was an exciting and life-changing experience. The show is dense and complex. It reflects this abundance and the joy we felt curating it together.

MA: Which is the role of Thomas Houseago, an artist, in curating this exhibition? His origins also?

CB: We really shared things, and being close to an artist allows me to get rid of a more classical way of thinking about exhibitions, to authorize the intuitive part, and Thomas is a deeply generous person, so the exchanges between the three of us have always been very dynamic.

TH: Each of us had a role, a story, a body of work, and our own ideas. We all brought ideas into the show that carried a personal meaning and importance. But at the same time also the discussions the three of us had became part of my work and personal thinking. Muna has transformed the way I see my role as an artist. Caroline has been, over the past 10 years, an incredibly important presence in providing feedback, critical discussions and intellectual “permission” that I have not often given myself in the past. They are both incredibly strong thinkers and therefore each of us has provided counterbalances for the other. My work in the exhibition was curated and chosen by Muna and Caroline. At the same time, I curated Muna’s presence in the exhibition. Her film and photos are central to the Cube and the exhibition as a whole. We are all in this exhibition as a collaborative body: artists, individuals and curators.

MA: “I may not really like this work but it’s going to be in a show in a way that’s respectful.” This sentence by Muna El Fituri sounds like the exhibit’s statement. The show seams about something that matters, into one’s own subjectivity and into society.

MA: “I may not really like this work but it’s going to be in a show in a way that’s respectful.” This sentence by Muna El Fituri sounds like the exhibit’s statement. The show seams about something that matters, into one’s own subjectivity and into society.

CB: Yes, we could absolutely say that, we are all with those questions that go through each of us: wars, racism, inequality, poverty, etc…

TH: We wanted to get away from a show that was chic, seductive or about taste. We knew that we would all include artwork that we didn’t necessarily like, but we realized it wasn’t important. We have to keep redefining the way we think about art and its potential, and I think I believe to bring it in closer to life… Some themes emerged that reflected our concerns and hopes. The body is a central theme – that somatic experience of the world – but also as a metaphor, the exhibition as a sensory exploration. The hope we must have in humanity but also its potential for disaster and catastrophe – how important is the vulnerability of the body – that we embrace our vulnerability as a true source of strength. We need to reframe art, pull it out of restrictive academic tropes and remind ourselves of how artworks call on us. They remind us to think about our bodies, right here, and our role in the world right now. That the stakes and implications of being alive are happening to us at the moment, art asks for a positive change in ourselves, present and immediate. Art then asks our commitments to the world – that we leave it with more beauty, not less.

MA: How did you solve the curatorial struggle to try and show something that is typically hidden engaging the physical presence?

MEL: It is hidden because we live in a society completely cut off from nature – from our place in this world as human beings. Art is what differentiates us from many species. Reconnecting with that ability to make art allows us to use in the way it was meant. We evolve through art. We connect through art.

TH: We quickly realized that it was important to emphasize that we all inhabit a body. We all experience birth, death, love, sex, vulnerability and fear. The rooms begin to define themselves through these primordial, primal feelings. If you look at art history, you always try to remind us that we live in a body, in a society, in social and personal constructs, in traumas that can take us away from ourselves. It has been one of my great joys and revelations to see these connections emerge organically among artists and to see how artists who made specific works for space, like Saul Fletcher, for example, created such powerful pieces.

MA: The death room, with works by Karon Davis, Henry Taylor, Rodin, Marlene Dumas and Luc Tuymans sounds very exciting. Which is the side you decided to show of death in this case? Its characteristic of being never ambiguous?

MA: The death room, with works by Karon Davis, Henry Taylor, Rodin, Marlene Dumas and Luc Tuymans sounds very exciting. Which is the side you decided to show of death in this case? Its characteristic of being never ambiguous?

CB: Well, death is the obsession of the human being since always and in different ways according to the different cultures, in a way that room I imagine calls into question the fear of it, to face it instead of escaping that fundamental question.

TH: Like sex, death is a universal experience. I was just reading that there is death in every birth and being born sends us back to death. As artists, it’s important to face death in all its aspects and look at it closely.

MA: Ana Mendieta is one of the artists that naturally caught best my attention, especially through her photographs. Is it true, as suggested by Helen Molesworth, that “she haunts many of these rooms?” In which way?

CB: Many women haunt the rooms, and we are super happy to have included Valie Export as well. Ana Mendieta is a fantastic artist for all of us, and she is one of the first to have changed the language with women’s body, but also with women’s power, and this is one of the questions we tried to raise in the exhibition.

MEF: An important aspect of the exhibition, which we discussed at length, was to make room for other artists not included in the exhibition. To use a cliché, it is Proust’s perennial Madeleine. We hoped to encourage this kind of thinking, a meditation on significant pioneer artists who were instrumental in creating movements by invoking them through suggestion. We joke a lot about how we could fill many more spaces if left to our own devices! The library has become an interesting solution. These artists we loved, and who were not included in this show, live in books and on the magnetic board. Their presence is felt throughout the show and the publications serve as a delicate reminder of those stories that this time we were unable to tell.

TH: Muna brought up Anna quite quickly for the show, and we had all agreed on her work. But as the show formed and grew, we realized there were certain artists that did begin to “haunt” all the spaces and brought a strong almost guiding role through the show. The same is true for Betye Saar.

MA: The eclectic choice of artists reflects also on giving a lot of space to Betye Saar, as kind of representative of California. What is exceptional about this dedicated room? “Saar does it all” calls once again Molesworth.

CB: She is one of the first black American voices that has influenced so many people and some even in the exhibition, such as David Hammons, Henry Taylor, etc., so we didn’t want to show a work, but have more of hers, since it is less known in Europe (even if she had an exhibition at Fondazione Prada, and has currently an exhibition at LACMA and MoMA!). We called the Yeiling room while she and Lynn Foulkes are screaming about inequality, racism, etc… and she is so free in her reference…the way she proposed the works, from an invented creed to a condition of exile… so many thought sand feelings can raise from her work!

MEF: Betye Saar is a fantastic and extremely important artist. She represents a voice that you don’t see often. Her incredibly complex and long career (she is 93 years old) has allowed us to deepen her work in the context of her exhibition. I think it was natural and instinctive to highlight a couple of artists, to allow a sort of rhythm and flow throughout the exhibition. Betye Saar seemed to me an objective choice, in the way the studio allows the visitor to take a breath having a larger group of artworks by a single artist that modulates and harmonizes. I hope it also allows for reflection on all the works of the artists in the exhibition that are yet to be seen and discovered. I feel it brings a sense of harmony and cadence to the exhibition.

TH: The art market or artworks as currency have played no part in our thinking. We had the opportunity and the privilege to be resolutely removed from that system and to live in the glorious space of artworks and their true meaning and potential. So, if we included an artist, the consideration was directed to the works, philosophy, humanism and ability to confront other works, themes, discussions in the exhibition. As I said, Betye Saar’s work has become one of the guiding principles and presences in the exhibition. The work embodies some of the key themes, the transforming power of art in personal healing, but also in social change. Its ability to draw on higher spiritual and emotional levels, the work extends beyond its boundaries.